by Nic Haygarth | 17/12/16 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

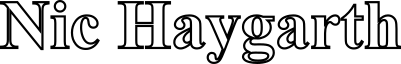

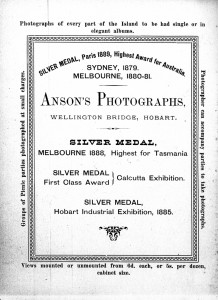

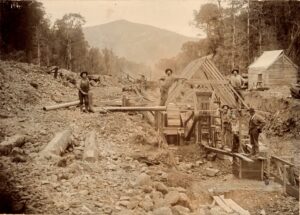

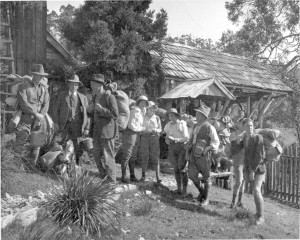

The Wainwrights at Mount Cameron West (now returned to the Aboriginal people, as Preminghana) during the late 1890s. Sunday best is adopted for the photographer. The girl standing at front beside her parents Matilda and George is probably May, the boys on horseback are probably George, Dick and Harry. Photo courtesy of Kath Medwin.

In 1889 Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) local agent James Norton Smith advertised for ‘a trustworthy man to snare tigers [thylacines or Tasmanian tigers], kangaroo, wallaby and other vermin at Woolnorth’, the company’s large grazing property at Cape Grim. The annual wage was £30 plus rations and a £1 bounty for each thylacine killed.[1] Applications came from Tasmanian centres as far afield as Branxholm in the north-east and New Norfolk in the south. One, written on behalf of her husband, came from Rachel Nichols of Campbell Town. She was the mother of then eleven-year-old Ethelbert (Bert) Nichols, the future hunter, Overland Track cutter, highland guide and Lake St Clair Reserve ranger.[2]

However, none of these applicants got the job. The man chosen as ‘tigerman’, as the position was known within the VDL Co, was George Wainwright senior, who arrived ‘under a cloud’ as George Wilson and departed in 1903 when convicted of receiving stolen skins.[3] Was he a relation of Woolnorth overseer James Wilson, or how was he selected for the job?[4] And what was a tigerman anyway?

George Wainwright was born in Launceston in 1864, and seems to have a not untypical upbringing for the poorly educated child of an ex-convict father, featuring family breakdown, petty crime, shiftlessness and suggestions of poverty.[5] As a young adult he measured only 162 cm (5 foot 3 inches), with a dark complexion and dark curly hair. The scar under his chin may have the result of rough times on the streets of Launceston.[6] Food may have been scarce. At thirteen he faced court with another boy on a charge of stealing apples (the case was dismissed for lack of evidence).[7] In 1883, his employer, Launceston butcher Richard Powell, had the nineteen-year-old arrested on warrant (that is, in absentia) on a charge of breaching the Master and Servant Act.[8] He had run off to Sydney, describing himself as a cook.[9]

George had returned to Launceston by October of that year, when his mother, now known as ‘Mrs T Barrett’ (née Caroline Hinds or Haynes or Hyams), ran a public notice instructing clergymen not to marry her son to anyone, he being under age.[10] Presumably George had Matilda Maria Carey (1863–1941)—or her pregnancy—in mind, because the couple were soon united, and soon separated.[11] In 1885 Matilda prosecuted George for deserting her and George junior, having not sent her any money for six months. It was revealed in court in Melbourne that George had recently been a grocer’s assistant, but now was working in a Brunswick (Melbourne) brick yard. Matilda Wainwright was then living with her father-in-law William Wainwright in Launceston. She claimed he showed her little sympathy, having sold all her furniture and told her to seek a living for herself. George Wainwright was freed on agreeing to pay her 10 shillings per week.[12]

Interestingly, in Victoria he was known to police as George Brown, ‘alias Wainwright’.[13] Presumably he returned to Launceston sometime between 1885 and 1889—and changed his name to George Wilson! He may have been the George Wilson who was in Beaconsfield in 1886 and 1887.[14] Perhaps he became a protégé of James Wilson, the Woolnorth overseer, and perhaps that man’s intervention secured Wainwright/Brown/Wilson the tigerman job at Woolnorth. James Wilson had coined the term ‘tigerman’ to describe the Mount Cameron West shepherds in the period 1871–1905. Convinced that thylacines were killing their sheep, the VDL Co gave the Mount Cameron West man the additional job of maintaining a line of snares across a narrow neck of land at Green Point, which was believed to be the predator’s principal access point to Woolnorth. Otherwise, the tigermen were actually standard stockmen-hunters, charged with guarding sheep and destroying competitors for the grass.

George Wilson and his family originally occupied a one-room hut at Mount Cameron West. In 1893 George Wainwright, as he was now known again, apparently told a visitor that he received £2-10 for each thylacine killed—£1 from the VDL Co, £1 from the government and 10 shillings for the skin. In the years 1888–1909 the Tasmanian government paid a bounty on every thylacine carcass submitted to police. However, nobody by the name of Wainwright ever collected a government bounty: in fact only two VDL Co tigermen, Arthur Nicholls and Ernest Warde, personally collected government bounties while working for the company.[15] The thylacine carcasses appear to have been sold through intermediaries, chiefly Stanley merchants Charles Tasman (CT) Ford (1891–99) and (after Ford’s death) William B (WB) Collins (1900–06). Ford, who also drove cattle down the West Coast to Zeehan and bought VDL Co stock, was a regular visitor to Woolnorth.[16]

In 1893 Wainwright had about 60 springer snares set for wallaby, pademelon and brush possum.[17] Ringtails were the dubious beneficiary of technological change, as the commercial manufacture of acetylene or carbide during the 1890s revolutionised ‘spotlighting’. Using an acetylene lamp to spotlight nocturnal animals was a vast improvement on the traditional method of shooting by moonlight, since some animals, especially the ringtail possum and ‘native cat’, were ‘hypnotised’ by the lamp, remaining rooted to the spot. It was not the ideal hunting technique for a grazing run, however, let alone for a solitary shepherd. Usually, two men worked together, one ‘spotting’ the animals with the acetylene lamp, the other shooting them. The lamps which shooters used frightened stock, and sometimes shooters’ dogs ran amok with grazing sheep. More significantly for the hunter, shooting the animal in any other part but the head damaged its pelt. Acetylene fumes were also unpleasant for the hunter, and the battery sometimes gave him an unexpected ‘charge’.

More money was available for a living tiger than a dead one. By Wainwright’s time, thylacines were in demand from zoos. In 1892 James Denny caught one alive at the Surrey Hills and sent it to the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne.[18] In 1896 CT Ford was asked to procure live tigers for a circus. Wainwright obliged by capturing a thylacine alive and sending it into Stanley, where there was ‘a little excitement … to see “the tiger”’ before it was shipped to Sydney.[19] This thylacine capture does not appear in the extant Woolnorth farm journal record (the journal for 1896 is missing) or in any other surviving official records for Woolnorth. Since the animal was not killed, Wainwright received no VDL Co or government reward for it.

In 1897–98 a new hut was built for George and Matilda at Mount Cameron. They would need it. Six children—George, Alf, Dick, May, Harry, Gertrude and Robert—gave them plenty to worry about in such an isolated place. If that was not enough, Matilda was reportedly ‘very ill’ in July 1893 and ‘badly hurt’ in January 1894, while in May 1900 Woolnorth overseer W Pinkard had to fetch medicine for her from Stanley.[20]

By 1900 George and Dick were already showing their prowess as tiger snarers, and one of the Wainwright boys was digging potatoes.[21] With their father sometimes helping out elsewhere on the property, fetching cattle from Ridgley or a stockman from Trefoil Island, the children quickly developed a range of skills which ensured that they could work on the land independently.[22]

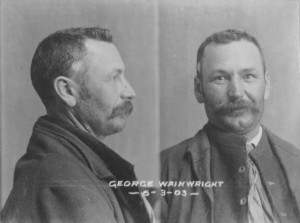

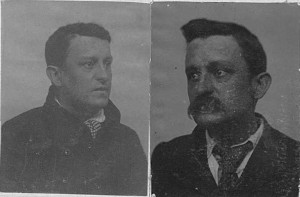

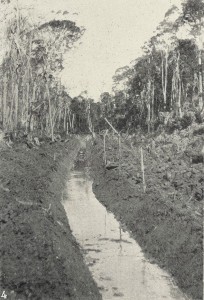

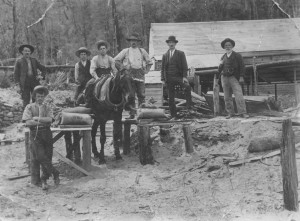

George Wainwright’s mugshot, 1903. Courtesy of TAHO.

Wainwright’s imprisonment in 1903 gave them that opportunity. The story of his crime of receiving 298 wallaby, 298 pademelon, 17 tiger cat, 2 domestic cat and 10 brush possum skins stolen from William Charles Wells contains insight into hunting at Mount Cameron West and on Woolnorth generally. Wells was caretaker (hunter-stockman) for a farm at Green Point south of Woolnorth, near where the VDL Co arranged its snares. The owner of the property, Thomas John King, had stayed with Wainwright in the Mount Cameron Hut in July 1902 after fetching the skins from the farm. The skins disappeared overnight after being left outside the hut in a cart. Suspicion fell on Wainwright not only because his was the only hut in the area but because he had previously tried to buy the skins at a price which was refused. Police alleged that in September Matilda Wainwright drove a buggy containing the skins to the port at Montagu to be loaded on the ketch Ariel.[23] It was now close season, so Wainwright wrote telling Stanley storekeeper WB Collins that he was sending down some out-of-season skins and suggesting that he ask the police to let them pass. Wells claimed to have identified 23 of his stolen skins in Collins’ store.[24] Proof that Wainwright was guilty centred on Wells’ identification of an unusually light skin among those Wainwright had sent to market. A search conducted among the skins of three Launceston skin merchants, Lees, Sidebottom and Gardner, revealed only three or four skins matching the one identified by Wells, confirming the distinctiveness of the skin and strengthening the case against Wainwright.[25]

Launceston merchant Robert Gardner testified that he had known Wainwright for 25 years, having employed him when he (Wainwright) was a boy, and that he had done business with him for several years, finding him straightforward and honest. He had bought wallaby skins from Wainwright regularly.[26] Despite this testimonial, Wainwright was given a twelve-month sentence for receiving stolen property. Thirty-nine years old, he died in the Hobart Gaol of heart failure prompted by acute pneumonia only four months into that sentence.[27]

Today a relatively young man’s death in custody would provoke an inquest. However, the harshness of Wainwright’s demise seems in keeping with the harshness of his sentence and the general torpor of working people’s lives more than a century ago. George must have done something right as a hunter and provider, because he left wife Matilda £305—more than ten times his annual stockman’s wage.[28]

Charged with nothing, Matilda Wainwright stayed on as cook at Woolnorth, although only because no one else could be found for the job. ‘I would have preferred anyone else rather than Mrs Wainwright’, new VDL Co agent AK McGaw lamented, ‘and now that she is there I am not altogether satisfied that her influence is for the best. Of course I find her appointment does not answer I will have no hesitation in terminating it’.[29] McGaw had advertised for a married couple to replace the Wainwrights.[30] He effectively got one when the widowed Matilda married the new overseer, Thomas Lovell, while her sons, good workmen, also had a future at Woolnorth. As a woman and mother, remarriage was her only option anyway. George Wainwright junior would carve out his own long career as a VDL Co stockman.

[1] ‘Wanted, at Woolnorth’, Daily Telegraph, 9 August 1889, p.1.

[2] Rachel Nichols to James Norton Smith, 8 August 1889, VDL22/1/19 (Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office [afterwards TAHO]).

[3] AW McGaw, Outward Despatch no.16, 1 June 1903, p.151, VDL7/1/13 (TAHO); ‘Death of a prisoner’, Mercury, 15 July 1903, supplement p.6.

[4] On the bottom of J Lowe’s application for the job is written in pencil ‘Geo Wilson also’. Everett was the reserve choice: on the back of his application is written ‘If man, at present engaged—not successful will write JL again’. See J Lowe application 9 August 1889 and J Everett application, 19 August 1889, VDL22/1/19 (TAHO).

[5] For William Wainwright (1810–87), see conduct record, CON33-1-90, TAHO website, http://search.archives.tas.gov.au/ImageViewer/image_viewer.htm?CON33-1-90,207,205,F,60, accessed 17 December 2016.

[6] ‘Miscellaneous information’, Victoria Police Gazette, 19 August 1885, p.232.

[7] Birth registration 60/1864, Launceston; ‘Police Court’, Cornwall Chronicle, 7 February 1877, p.3.

[8] ‘Launceston Police Court’, Tasmanian, 22 April 1882, p.432; ‘Launceston Police Court’, Launceston Examiner, 7 February 1883, p.3.

[9] He arrived in Sydney from Launceston on the Esk, 9 February 1883, New South Wales, Australia, Unassisted Passenger Lists, 1826–1922.

[10] Advert, Launceston Examiner, 31 October 1883, p.1.

[11] Marriage registration 677/1883, Launceston. They married 7 November 1883, George William Wainwright was born seven months later, on 12 June 1884, birth registration 371/1884, Launceston. Matilda Maria Carey was born in Launceston, 22 December 1863, registration 23/1864, Launceston.

[12] ‘Wife desertion’, Launceston Examiner, 29 August 1885, p.2.

[13] ‘Miscellaneous information’, Victoria Police Gazette, 19 August 1885, p.232.

[14] ‘Beaconsfield’, Daily Telegraph, 29 May 1886, p.3; ‘Beaconsfield’, Launceston Examiner, 15 January 1887, p.12.

[15] Nicholls: bounties no.289, 14 January 1889, p.127; and no.126, 29 April 1889, p.133, LSD247/1/1. Warde: bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, p.325, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[16] James Wilson to JW Norton Smith, 8 April 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[17] Austin Allom, ‘A trip to the west coast’, Daily Telegraph, 19 August 1893, p.7.

[18] ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 17 September 1892, p.2.

[19] ‘Circular Head notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 25 June 1896, p.2.

[20] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 10 July 1893, VDL277/1/20; 22 January 1894, VDL277/1/21; and 7 May 1900, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[21] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 13 and 14 June, 7 May 1900, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[22] Woolnorth Farm Journal, 22 September 1898, VDL277/1/24; 16 January and 5 March 1899, VDL277/1/25 (TAHO).

[23] ‘Supreme Court’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 14 November 1902, p.2.

[24] ‘Supreme Court’, Mercury, 15 November 1902, p.3.

[25] ‘The Wainwright case’, Examiner, 28 February 1903, p.6.

[26] ‘The Wainwright case’, Examiner, 27 February 1903, p.6.

[27] ‘Death of a prisoner’, Examiner, 15 July 1903, p.6.

[28] ‘Testamentary’, Mercury, 20 October 1903, p.4.

[29] AK McGaw to VDL Co Board of Directors, no.38, 2 November 1903, p.313, VDL7/1/13 (TAHO).

[30] Advert, Examiner 20 May 1903, supplement p.8.

by Nic Haygarth | 17/12/16 | Tasmanian high country history

Herbert and Rosina Murray with their daughters Esma and Doreen, c1922. Courtesy of the Goddard family.

In January 1906 Herbert Villiers Murray (1892–1959) was walking from the town of Waratah to work at Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, a small open cut tin mine operated by Anthony Roberts at which his brother was battery manager. Thirteen years old, he was fresh out of school. Herbert was an orphan, both his parents having died in his home state of South Australia. Since his Waratah guardian would not allow him to stay at the mine, he had no option but to tramp 8 km each day along the North Bischoff Road.[1]

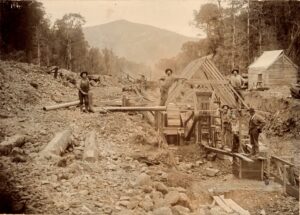

Eighteen-foot-diameter water wheel and two-head battery being erected at Weir’s Bischoff Surprise, North Bischoff Valley, in about 1905.

Passing the Happy Valley Face of Mount Bischoff, armed with his snake stick and crib bag, he followed the road until about 3 km further it turned into a sledge track cut for the old Phoenix battery. Rounding a spur, he saw a dog about 50 metres ahead of him, padding in the same direction. He whistled at the dog, which failed to respond as it trotted around the next spur. Herbert hurried on in his hob-nailed boots. He anticipated meeting the dog’s owner but, bafflingly, neither dog nor man came to greet him.

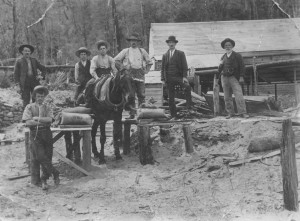

Are the Murray boys posed here on the pack-horse? This is another shot of the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise mine, with Cornish tin miner Anthony Roberts at right. Photo courtesy of Colin Roberts.

He reached the steep incline at the end of the metal road where the haulage was for the old Phoenix tin-dressing mill, then continued on along the sledge track, aware that the area was ‘the home and play-ground of a fair variety of snakes that travelled quite a lot in January and February—their mating period’. At last he came to the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise sawmill, and the plumber’s shop where the sluicing pipes were made. Had anyone seen a man or a dog? No. Herbert described the dog, and ‘to my surprise they told me that it was a Tasmanian tiger I was endeavouring to catch up to’.

In those days, herd of semi-wild goats roamed the valleys around Waratah and Magnet, sometimes being shot for their meat. Herbert wondered if a goat was the focus of the thylacine’s attention that day on the North Bischoff Road. He was not keen to be the tiger’s prey:

‘Fear must have obsessed me for I cut a much stouter snake-stick, also my eyes became more searching as each turn of the track or road came into view, also I heard many more bush noises when travelling to and from “The Valley”. My fear subsided as the days passed, yet the years and the ears were always on the alert.’

There were regular sightings of thylacines in the Waratah region at that time, especially along mining infrastructure in the bush: ‘A reliable prospector told me that he knew that four pups found in the decayed butt of a large fallen tree in the Savage River, had died from one shot from a gun, as they were of little or no value in those days’.[2] However, with scarcity the value of a live one grew. In 1925 the Waratah snarer Arthur ‘Cutter’ Murray advertised his captured tiger for sale in the newspaper before delivering it to the zoo in Hobart.[3]

By then the Mount Bischoff mine was a marginal operation, the tin price was low and there was little work in Waratah. Herbert Murray had married English girl Rosina Goddard and moved to Melbourne, leaving the likes of his namesake, ‘Cutter’ Murray, and Luke ‘Stiffy’ Etchell, to extricate the occasional tiger—dead or alive—from their necker snares.

[1] See Goddard family research, ancestry.com,

http://person.ancestry.com.au/tree/408869/person/-2071601523/facts

accessed 17 December 2016.

[2] Herbert V Murray, 6 Renown Street, North Coburg, Victoria, to the Animals and Birds’ Protection Board, Hobart, 11 July 1957, AA612/1/59 (TAHO).

[3] ‘For sale’, Examiner, 15 June 1925, p.8.

by Nic Haygarth | 16/12/16 | Tasmanian landscape photography, Tasmanian nature tourism history

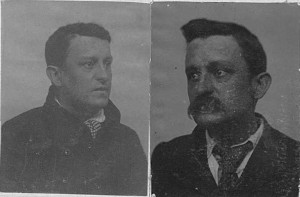

Joshua Anson’s 1877 and 1896 mug shots, from GD128-1-2, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office (TAHO).

Reinvention is part of the Australian convict story. Many convicts transported to the antipodes reinvented themselves as respectable society figures after serving their sentences. Joshua Anson’s surname was a byword for convictism, Anson being the name of a convict hulk which for years was stationed in the River Derwent, Tasmania. Born in Hobart with a hint of the stigma of convictism already attached to him on 29 October 1854, he would not only serve time and reinvent himself twice but he would pioneer convict tourism, making him almost a post-Modernist of the post-transportation era.

The second of three brothers born to Joshua Anson senior and Eliza Anson née Smith, Joshua Anson grew up to be a physically small man with large ambitions.[1] Unfortunately, his ambition as a landscape photographer shamed him before it famed him. In 1875, at the end of a three-year apprenticeship, 20-year-old Anson was placed in charge of his employer Henry Hall Baily’s Liverpool Street, Hobart shop, and offered an interest in the business. Anson was already a keen photographer, habitually rising at 5AM in order to utilise the morning light, and processing his own prints in his spare time in his home workshop.

About eighteen months after graduation as a ‘photographic artist’, however, Anson came under Baily’s suspicion. Four of the latter’s missing Souvenirs of Tasmania view albums were eventually found in Anson’s workshop. Further police searching revealed landscape and portrait prints, mounts and negatives stolen from Baily. Testimonials to Anson’s good character, including one from the photographer Samuel Clifford, failed to save him from a two-year gaol term for ‘larceny as a servant’.[2]

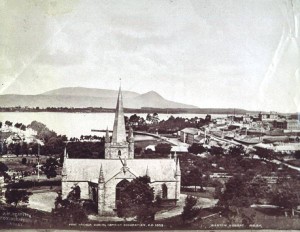

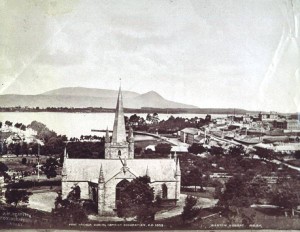

A shot of Port Arthur rebranded by JW Beattie. Joshua Anson was marketing the old penal settlement before Beattie began work as a professional photographer. Courtesy of TAHO.

He served eighteen months—not at Gothic Port Arthur, but at the Hobart Gaol in Campbell Street. In July 1879, after his release, Joshua and his brothers Henry (1853–90) and William (1857–81) Anson established a photographic studio at 132 Liverpool Street, Hobart.[3] This had been Clifford’s address until 1878, and the Anson brothers seem to have acquired the Clifford photo stock. Joshua’s experience with Baily and his own previous photographic efforts presumably gave the brothers a head start in this new enterprise. He set to work with a series of 26 10-inch by 8-inch views of the Hobart and Launceston regions, including Silver Falls, Mount Wellington, Hobart and Launceston Main Line Railway Stations, Launceston’s Princes Square, People’s (City) Park, St Joseph’s Church and School (in Margaret Street, Launceston), Corra Linn and Cataract Gorge.[4] The immediate purpose of this exercise was probably submission of a dozen scenic prints to the Sydney Exhibition during August 1879.[5] The ultimate purpose would have been to establish a souvenir trade in Tasmanian scenic views. The Tasmanian newspaper reported that Anson would supply his new images to the public at a moderate price, and suggested that ‘if he would mount them in convenient portfolios, they would become popular with strangers, as souvenirs of their visit to Tasmania’.[6]

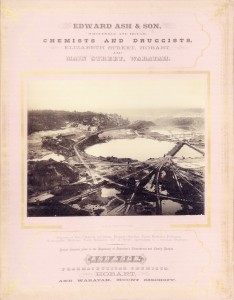

Beattie comes aboard … and so does the Mount Bischoff tin mine, in Just the Thing III, the Anson Studio advertising album from 1884. Edward Ash was a Hobart chemist and amateur photographer who not only set up a Waratah branch but started a newspaper in Waratah. This photo could have been taken by Ash or by Beattie. Courtesy of TAHO.

This is exactly what the Anson Brothers did. However, their biggest coup was recruiting Scottish immigrant John Watt (JW) Beattie, who became not only the shop manager but the firm’s leading landscape and portrait photographer. The Ansons needed help. All three were epileptics. Twenty-three-year-old William Anson died as the result of a swimming pool accident in 1881; Henry Anson, a married father, would eventually leave the firm but rely on Joshua’s financial help up until his death in 1890, aged only 36.[7]

Beattie has been credited with pioneering convict tourism in Tasmania, but the Port Arthur penal establishment was a subject of Anson photography from 1880, when it appeared in the firm’s Just the Thing photo album. The assumption that Beattie, who joined the Anson Studio two years later in 1882, infused it with his appreciation of history ignores the historical impulse that already existed among Hobart’s professional portraitists. It was almost obligatory in the 1860s and 1870s to photograph or paint the ‘Last of the Aborigines’. In 1880 Ansons photographed a 60-year-old pencil sketch of Hobart Town, featuring Aborigines, and both their ‘Photographs of Hobart and Surroundings, Huon Valley’ (1880?) and Tasmanian Views (1883) albums opened with a photo of the recently deceased Truganini, the former album giving her King Billy (William Lanne) as a consort.[8] . In 1884 ‘Mr Anson the photographer’ stepped off the fishing smack Surprise at Carnarvon, the sanitised name for Port Arthur, where he was reported to have shot several more Port Arthur images.[9]

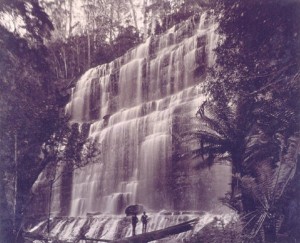

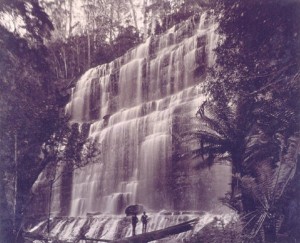

Browning Falls (Russell Falls) on the Russell River, probably shot for Anson Studio by JW Beattie and later re-branded as his. From Anson Studio’s Picturesque and Interesting Tasmania album (1890), courtesy of TAHO.

Anson Studio advert from Picturesque and Interesting Tasmania (1890), courtesy of TAHO.

Joshua Anson’s offer of partnership to his shop manager JW Beattie in 1890 not only demonstrates the high regard in which the latter’s services were held, but also Anson’s financial problems. Like many a businessman, he became bankrupt during the economic depression of the early 1890s. Court proceedings in April 1892 revealed that Anson had been in serious financial trouble for at least five months, struggling even to pay rent at his lodgings. [10] Part of his downfall was his speculation in shares in the Zeehan–Dundas mining field which had collapsed with the closure of the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land. He claimed to have little idea of the true state of the books until advised by an accountant, although this could have been a ploy to try to avoid culpability for his debts.[11] It was at this point that Beattie bought the Anson Studio, and with it the rights to all the Anson brothers photos taken not only by himself and Joshua Anson but the stock secured from Samuel Clifford. Many Anson Studio photos were re-branded ‘JW Beattie’.

Having lost his studio and his back catalogue, and still being subject to bankruptcy proceedings, Anson tried to re-establish himself as a photographer. Perhaps the strain showed when in March 1893 he was hospitalised with a head injury after collapsing during an epileptic episode in Collins Street.[12] He offered unsuccessfully to photograph lighthouses for the Marine Board of Hobart in July 1893.[13] He was finally discharged from bankruptcy in September 1893.[14]

How did Anson make a living? It is possible he worked for Beattie in his old studio, their positions reversed. In October 1895 he failed in an application to recoup £25 from the government for some Tasmanian tourism photos which had been displayed in the Agent-General’s Office in London years before.[15] With that effort to start afresh defeated, Anson made no further public appearances until May 1896 when he returned to the dock after nineteen years on a charge of robbery from the person. He was alleged to have stolen almost £33 from Strahan storekeeper Charles Perkins at the bar of the Royal Hotel. Anson, who was arrested at Mrs Hanson’s boarding house in Collins Street, appeared in court with bruises on his face resulting from two epileptic fits suffered while in custody.[16] Two months later he was found guilty of receiving and sentenced to twelve months’ gaol.[17]

Anson’s rap sheet records the legacy of epilepsy, noting scars on both side of his forehead. He also had a disfigured left thumb and was missing a second toe from some mishap.[18] When it seemed things could get no worse for Anson, while he was in gaol a newspaper advertisement was run threatening to sell his uncollected clothes.[19] He was released on 26 July 1897: ‘freedom’ was the single word recorded on his rap sheet.[20] Whereupon he disappeared. There is no record of Anson living or dying in Tasmania after that date, although of course he could have changed his name. Forty-two years old, he had plenty of time to start a new career if bankruptcy and two prosecutions for dishonesty could not be held against him.

It is possible that he re-established himself in Western Australia. In November 1897 a John Anson proceeded against a photographer named Flegeltaub for wages due in the Police Court in Perth, Western Australia.[21] In July 1898 a ‘Mr Anson, a photographer engaged by the government to procure photographs of the district for railway carriages etc’, visited Bridgetown in southern Western Australia.[22] Two months later he was on a similar mission at Albany, procuring photos of the harbour, King Georges Sound, the Denmark forests, and in the York area. His employer was named as the Under Secretary of Railways.[23] Taking scenic tourism photos for the government would have been a familiar task for Joshua Anson, and mimicked Beattie’s on-going role as photographer to the Tasmanian government. In October 1904 a John Anson was initially named as one of seven people who went missing when a yacht called the Thelma disappeared in a squall off Fremantle. The men had set out with the intention of visiting Garden Island.[24] However, later reports of the same incident omitted Anson and put the toll at only six people. Joshua Anson may well have become Joshua Anon, reinvented itinerant landscape photographer, posthumous portraitist, a man without a past in a post-convict world.

[1] Birth registration no.1476/1854.

[2] ‘Supreme Court: Second Court’, Mercury, 11 July 1877, p.2; ‘Supreme Court: sentencing’, Mercury, 12 July 1877, p.3.

[3] The Hobart Assessment Roll, Hobart Town Gazette, 1 January 1878, p.36 places Clifford at 132 Liverpool St; whereas Charles Hartam is both owner and occupier of that property at 1 January 1879, p.35. Anson Brothers first advertised their 132 Liverpool St ‘(LATE “CLIFFORD’S”)’ studio in the Mercury on 30 July 1879.

[4] ‘Photographic views’, Tasmanian, 19 July 1879, p.11.

[5] ‘For the Sydney Exhibition’, Mercury, 22 August 1879, p.2.

[6] ‘Photographic Views’, Tasmanian, 19 July 1879, p.11.

[7] ‘Fatal accident at the Domain Baths’, Mercury, 16 February 1881, p.2; ‘The accident in the Domain Baths’, Mercury, 24 February 1881, p.3; ‘Sudden death’, Mercury, 26 March 1890, p.2.

[8] Charles Woolley, for example, submitted portraits of Tasmanian Aborigines to the 1866 Intercolonial Exhibition (Mercury, 25 September 1866, p.3), while HH Baily painted Truganini, the so-called ‘last queen’ of the Aborigines (‘Pictures for the Sydney Exhibition’, Mercury, 5 August 1879, p.2). For the pencil sketch, see ‘An interesting relic’, Mercury, 2 April 1880, p.2.

[9] ‘Carnarvon’, Tasmanian Mail, 19 April 1884, p.20.

[10] ‘Bankruptcy Court’, Launceston Examiner, 14 April 1892, p.3.

[11] ‘Supreme Court’, Mercury, 24 May 1892, p.4.

[12] ‘Hospital cases’, Mercury, 17 March 1893, p.2.

[13] ‘Marine Board of Hobart’, Mercury, 29 July 1893, p.1.

[14] ‘Application in bankruptcy’, Mercury, 2 September 1893, p.3.

[15] ‘House of Assembly’, Mercury, 12 October 1895, p.1.

[16] ‘Alleged robbery’, Tasmanian News, 29 May 1896, p.2.

[17] ‘Second court’, Mercury, 29 July 1896, p.4.

[18] GD128/1/2, p.257 (TAHO).

[19] ‘Late advertisements’, Tasmanian News, 4 August 1896, p.4.

[20] GD128/1/2, p.257 (TAHO).

[21] ‘City Police Court’, West Australian, 9 November 1897, p.7.

[22] ‘Bridgetown’, Bunbury Herald, 2 July 1898, p.3.

[23] ‘England’s fleet’, Albany Advertiser, 13 September 1898, p.3; ‘York Municipal Council’, Eastern Districts Chronicle, 10 September 1898, p.3.

[24] ‘Disappeared in a squall: seven men missing’, Evening News (Sydney), 26 October 1904, p.4.

by Nic Haygarth | 12/12/16 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian nature tourism history

William Dubrelle Weston, aka ‘Peregrinator’. Photo from the Launceston Family Album, courtesy of the Friends of the Launceston LINC.

Ernest Milton Law, Weston’s hiking and legal partner. Photo from the Launceston Family Album, courtesy of the Friends of the Launceston LINC.

In March 1886 the pastoralist Alfred Archer of Palmerston, south of Cressy, guided two Launceston schoolboys across the Central Plateau through poorly charted country to Lake St Clair.[1] This was the first in a series of extraordinary highland excursions for sixteen-year-old William Dubrelle Weston (1869–1948) and fifteen-year-old Ernest Milton Law (1870–1909). Later adventures would include probably the first bushwalk to the Walls of Jerusalem, visits to Great Lake and Mount Barrow, and the first two tourist trips to Cradle Mountain—‘the summit of our ambition’.[2]

On most of these expeditions they would be joined by two chums they knew from the Launceston Grammar School, the brothers Richard Ernest Smith (1864–1942), known as Ernest or ‘Old Crate’, and Alfred Valentine ‘Moody’ Smith (1869–1950). Weston’s letters from the period show the friends’ high-spirited camaraderie, and how hiking relieved the stresses of study, career, faith, self-discipline and social life during the transition from adolescence to manhood. Bushwalking was already popular in Tasmania, with accounts of highland excursions appearing regularly in newspapers.

Cradle Mountain and Dove Lake, as Peregrinator’s party would have seen them, without tourist infrastructure. HJ King photo courtesy of Maggie Humphrey.

Why did they choose Cradle Mountain in 1888? The peak received few visitors. No ascents are recorded between James Sprent’s trigonometrical survey in about 1854 and that by Dan Griffin and John McKenna in March 1882.[3] The discovery of gold on the Five Mile Rise on the western side of the Forth River gorge had increased traffic towards Cradle on the old Van Diemen’s Land Company Track, but the peak itself remained more remote from Launceston than even Lake St Clair was.

However, the Launceston Grammar old boys were now confident, independent bushwalkers. The Smith brothers were in charge of the commissariat. Alf was the hunter of the party, armed with a rifle. Currawongs and green parrots were landed on the way to Cradle Mountain, although a snake despatched by two weapons was left off the menu. Porridge, bread and butter, johnny cakes and beef fed the party at other times. Water proved so scarce that on the Five Mile Rise (near today’s Mail Tree or Post Office Tree on the Cradle Mountain Road) it was squeezed out of moss, a decoction that not even the addition of the emergency brandy and whisky could make palatable.

The party attempted to reach Cradle not by today’s tourist route across the Middlesex Plains, then south to Pencil Pine Creek, but by the direct route which took them into the deep, scrubby Dove River and Campbell River gorges. This was the hunters’ route to Cradle, but Weston’s party soon lost their way. With supplies dwindling on their fifth day out, there was nothing for it but to turn for home. Weston, who had taken to writing under the pseudonym of ‘Peregrinator’ or ‘Mr Peregrinator’, had been tantalised by Cradle’s ethereal heights:

‘Before us rose the imposing mass of the mountain; to our right was another stupendous gorge; and high above it and us a splendid eagle sailed in clam serenity, above all the ups and downs of terrestrial life and toil.’[4]

Ernest Smith wrote of the same vista months late: ‘I have that scene as vividly before me now while I am writing as if I were there, and I shall have until I die’.[5] There was no question but that they would return.

Two summers passed before ‘the old Company’ could reassemble, and they did it without ‘Moody’ Smith. ‘At last Mr Peregrinator and two friends got loose from their respective occupations’, Weston opened his second Cradle Mountain narrative. Infrastructure had improved in the three years since their last Cradle adventure. The Mole Creek branch railway, a new Mersey River bridge and the Forth River cage (flying fox) expedited travel. For a second time Fields’ Gads Hill stockman Harry Stanley doubled as their official weighbridge. That this time their packs averaged about 49 lbs (22 kg) each, compared to 43.5 lbs (20 kg) on the previous trip, suggests heavier provisioning in an effort to secure their goal. Extra cocoa, ship’s biscuit, porridge, rice and tea probably came in handy—as did bushranger Martin Cash’s autobiography—when time lost to rain extended the trip to thirteen days.

The four chose the easier route via Middlesex Station, which proved a useful staging-post, and provided a stockman to guide them onwards. Like other early Cradle climbers, Peregrinator’s party mistook the more obvious north-eastern end of the mountain for the summit. They then had to dodge the series of intervening spires to reach the true summit at the south-western end, where they found the timber remains of James Sprent’s trigonometrical station.[6] Standing on Cradle’s pinnacle—the ‘summit of our ambitions’—in perfect stillness, with the island spread out below him, Weston struck a melancholic note:

‘We had been seeking grandeur of nature and now we beheld its plaintive softness … Sound, there was none. Yonder stood the frowning buttresses of the mountain … many a glistening silver line revealed a stream plunging in headlong fury down the distant slopes, and there asleep in the very arms of nature herself lay a tiny lakelet [probably Lake Wilks], whose breast was sacred e’en to the evening zephyr. How comes it that so much of this world’s intensest scenes of beauty are set in a minor key?’

Sadly, Weston recognised that the party’s hiking career ended then and there on the summit. Now aged from 20 to 26 years, the men would soon sacrifice their youth and their physical prime to adult responsibilities. Yet Weston’s usual picaresque banter, historical footnotes and topical commentary enlivened their extraordinary ‘final push’ home—about 45 km from Middlesex Station to Sheffield by foot in a day. Peregrinator’s romantic description of the jewels of the night guiding his descent from the Mount Claude saddle must have raised eyebrows among those who knew the place only for labour with pack-horse and bullock team on their way to the gold mines on the upper Forth River. After alighting from the train in Launceston, the trio made straight for the photographer’s studio and there immortalised ‘the old Co’s’ swansong. ‘The closing scene was enacted some days later when we called for our proofs’, Peregrinator concluded.

‘On our appearance we were some time making our photographer perceive that we were the same individuals, who had called in with the black billies and aspiring beared a few days before. And now the Cradle trip like many like it remains a please reminiscence of the past and a joy for the future.’[7]

William Dubrelle Weston (2nd from left) with guide Bert Nichols (3rd from left) before setting out from Waldheim to climb Cradle Mountain in 1933. Fred Smithies photo courtesy of Margaret Carrington.

It is unlikely that Alf ‘Moody’ Smith, who became a Church of England minister in New South Wales, ever stood on the summit of Cradle Mountain. Ernest Law never repeated the adventure, dying, tragically, of typhoid in 1909, aged only 38. Neither Ernest Smith nor Weston renounced hiking altogether, with the former leading boys on mountain treks in his career as a school-teacher. But only Weston returned to the top. In 1933, 45 years after he first tackled Cradle Mountain and now 64 years old, he noted in the Waldheim Chalet visitors’ book at Cradle Valley:

‘With thankfulness to God’s goodness it is recorded that WD Weston who led the first Launceston party (late Ernest M Law and Mr Richard Ernest Smith) in December 1890–January 1891 (ascent Jan 2nd 1891) reascended to the trig on the Cradle 28th December 1933’.[8]

Ironically, the urban conqueror of Lake St Clair, the Walls of Jerusalem and Cradle Mountain more than four decades earlier, was now led to the summit by Overland Track guide Bert Nichols, a bushman fifteen years his junior. It is fitting that such an early spruiker of highland tourism should return to walk part of the ‘new’ track that popularised the region.

[1] ‘The Tramp’ (WD Weston), ‘About Lake St Clair’, The Paidophone, vol.II, no.7, September 1987, pp.7–8; ‘Shanks’ Ponies’ (WD Weston), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Launceston Examiner, 22 December 1888, p.2.

[2] See Nic Haygarth, “’The summit of our ambition”: Cradle Mountain and the highland bushwalks of William Dubrelle Weston’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.56, no.3, December 2009, pp.207–24.

[3] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Cradle country’, Tasmanian Mail, 8 February 1897, p.4.

[4] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Notes of a trip in the vicinity of the Cradle Mountain’, Colonist, 17 March 1888, p.4.

[5] RE Smith to WD Weston, date illegible, CHS47, 2/55 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery [henceforth QVMAG]).

[6] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Up the Cradle Mountain: no.3’, Launceston Examiner, 4 March 1891, supplement, p.2.

[7] ‘Peregrinator’ (WD Weston), ‘Up the Cradle Mountain: no.5’, Launceston Examiner, 11 March 1891, supplement, p.1.

[8] Waldheim Visitors’ Book, vol.2, p.8, 1991:MS0004 (QVMAG).

by Nic Haygarth | 10/12/16 | Britton family history, Circular Head history

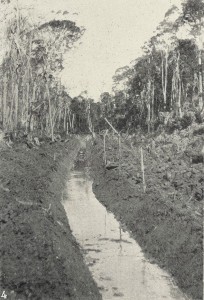

Winching a log out of the Welcome Swamp, 1923. From the Weekly Courier, 6 September 1923, p.21

Another shot of Welcome Swamp drainage, a familiar scene on the dolomite swamps of Circular Head in the first half of the 20th century. From the Weekly Courier, 6 September 1923, p.21.

The rapaciousness of the Circular Head timber industry was captured in Bernard Cronin’s novel Timber Wolves, published in 1920, the year before the establishment of the Tasmanian Forestry Department in an effort to make the industry sustainable. Mainland timber contractors and local operators tried to squeeze out competitors by securing strategic leases in front of existing working leases, cutting off transport routes and making expansion impossible:

‘Did you ever hear of “dummying”? These timber wolves go to the limit [of their timber quota] in their own names and put up dummy agents to cover the rest. It’s illegal, but what does that matter. They’s [sic] no one ever asts [sic] the question so long as the rental and royalties and so on are paid regularly. The while system is rotten to the core … We got to take the price they offer us, or let the timber rot …’[1]

Conservator of Forests Llewellyn Irby read Timber Wolves before visiting Smithton in 1922. ‘This is the worst place in Tasmania for toughs’, he wrote

and is part of the locality referred to in ‘Timber Wolves’ so you can imagine what we have to deal with. We have had a lot of trouble with a chap who is the worst scoundrel in the district. He has the reputation of being a man eater, has nearly killed two men by kicking them when down, while two or three others go through life minus half an ear, a piece he has bitten off.

This was Bill (William Henry) Etchell, whom Phil Britton described somewhat tactfully as ‘a notorious strong man, opportunist leader of men, hard drinker’. According to Phil, Etchell would pay his men well, then win back much of their wages in card games at the pub. Irby feared stronger tactics:

As he was looking for me I felt a tingling in my ears and as when drunk he is absolutely murderous and we had seized his logs; I carried my gun … if they are the ‘Timber Wolves’ we are the forest bloodhounds and intend to clean them up …[2]

Nor were rough tactics restricted to sawmillers. By 1921 the success of the Mowbray Swamp reclamation had convinced the government to drain the Welcome, Montagu, Brittons and Arthur River Swamps. The Surveyor-General stressed the importance of reclaiming

a large area of swamp lands, now lying in useless waste, but which when reclaimed and opened up will form one of the largest and best agricultural and dairying propositions in the state.[3]

Disappointment followed. The development of the Smithton dolomite Welcome Swamp near East Marrawah (Redpa) was a comparative disaster. Drainage was inadequate, the scheme was extremely expensive, and superintendent of the works, Thomas Strickland, faced accusations of foul play. Strickland resigned with the job incomplete after being criticised by a Royal Commission into the reclamation scheme.[4] For years afterwards no land on the Welcome Swamp was ploughed.

Harvesting blackwood by bullock team near Smithton. From the Tasmanian Mail, 12 September 1918, p.19.

The summer of 1923–24 was so wet that it was impossible to haul logs out on flat land by bullock team, reducing productivity, but by February 1924 the bush was drying out. ‘We may have to get a bullock driver ourselves’, Mark Britton told Jim Livingstone, ‘as you cannot depend on CW [Charlie Wells] …’ Wet weather also prevented laying down more tramway, so the chance was taken to overhaul the locomotive instead. With blackwood hard to remove from the bush, attention was switched to cutting hardwood from Robinson’s land, where tracks were opened up for the winder to work. Brittons also applied to remove blackwood from a block of crown land which they believed could only be reached by log hauler from spur lines on their own lease. At least £30 of work was done in anticipation of gaining the lease—only to discover it had been granted to Frank Fenton, one of the sons of CBM Fenton and a grandson of James Fenton, pioneer settler at Forth. He was a new player in the timber game who had built a steam sawmill at the foot of the Sandhill. Mark Britton continued:

We do not know if Fenton knows about it [the blackwood on his lease] anyway we do not intend to tell him at present … some of the mills are going bung around here and more will follow we are thinking soon.[5]

Mark Britton (with beard), Arthur Coates, Pat Streets, H Shaw and another man loading dry blackwood boards.

To Mark, as he explained to Llewellyn Irby, this was a clear case of dummying by Fenton. He went on to explain that there was no longer enough timber on Crown land to keep a small mill cutting for three months of the year. Brittons could have attacked the disputed blackwood by steam hauler. Fenton could not, making it impossible for him to obtain the whole of the timber.[6] Not only would timber be wasted, Mark claimed, but Fenton’s method of removing the timber could destroy roads designed for lighter traffic and built by men working legitimately.[7]

As Mark complained, by October 1925 Brittons were watching blackwood logs that they themselves had felled being removed by Fenton to his mill, using tracks they had cut and cleared:

Does your department allow such proceedings if not to whom must we apply for justice please reply at once re the matter, we do not want those tracks cut up and if your department is not responsible we will take proceedings ourselves.[8]

In truth, this was a case of Brittons letting an opportunity slip. The Forestry Department had advised the company to take up the lease, but they did not see its value, as Phil Britton remembered:

I blamed myself too, as I was told to have a look at it which I did, but not having the knowledge of assessing the volume of timber let the offer slip.[9]

Fenton saw its worth. He applied for the area, built a steam sawmill at the foot of the Sandhill and added to his holdings another 15,000 acres held by Chapman, a clerk for Cumming Bros in Burnie. He built a tramline to this new area but cleaned up the handy timber at Christmas Hills with trucks and Aub Sheen’s horse team:

Wet or fine those logs kept coming into Frank Fenton’s mill. Hazel Jacklyn was the steam engine man who kept the steam up and sharpened the circular saws. A twin sawmill and breast bench and docker were common in those days and turned out large quantities of furniture boards and flooring, all quarter cut and racked and held in stock till the Depression passed.[10]

Fenton would be the only sawmiller to beat the slump of the mid to late 1920s.

Bill Etchell was another who gave rival sawmillers a run for their money. In the early 1920s he ran out of logs on private property at Christmas Hills. He moved his portable steam engine and spot sawmill to Edith Creek, and in October 1924 relocated again, this time at the Salmon River to exploit the stands of blackwood in that area. At that time hardwood was almost unsaleable, whereas there was a strong market for blackwood.[11]

Etchell was in the habit of applying for large timber leases in front of another sawmiller, cutting off his future supply. After moving his mill, in March 1925 Etchell applied for and won a lease beyond where Brittons were working at Edith Creek. Mark Britton complained that his company should be given preference in this area,

seeing that we have opened up the way to obtain the timber having spent the best part of our time and money in the venture and then to find ourselves outdone by what appears to us speculators and adventurers that just take up areas wherever they see a blank space on the chart …

Mark pointed out that the Edith Creek mill to which Etchell was supposed to be going to mill the timber was now at the Salmon River. Anyone acquainted with the rough country concerned, Mark claimed, ‘would realise the absurdity’ of trying to build a tramway into it, although, apparently, the timber on it would have been accessible from Brittons’ existing tramway network.[12] Brittons won out on this occasion.

Careful assessment of costs had to be made ahead of taking up a permit, taking into consideration the cost of constructing and maintaining tramways and haulage. By December 1925 Brittons had cut all the blackwood on their leases with the exception of an 800-acre lease and were looking for new leases.[13]

A consummate ‘land shark’: Major Musson

Tasmania was in a perilous economic state during the 1920s. As well as sawmillers, many farmers, including returned soldiers, struggled for survival. The Primary Producers’ Association (a forerunner of today’s Tasmanian Farmers and Graziers’ Association) was established to lobby politicians about the needs of farmers.

However, not everyone was on the side of the farmer. Major Richard William Musson (not to be confused with promoter of the pulp and paper mill at Burnie, Gerald Musson) first appeared in Tasmania in December 1922 as a representative of ‘one of the leading insurance businesses’. He was noted as ‘a singer of great repute, well known in Manchester’, and had been a member of the Welsh Fusiliers during World War I.[14] The businesses he was involved in included the Flax Corporation of Australia, the Renown Rubber Ltd, the Rapson Tyre Company and the Primary Producers’ Bank of Australia, which opened its first branch at Wynyard in December 1923 before extending its custom across the state.[15] In the years 1923–25 Musson lived in Wynyard, demonstrating his talent for instant rapport by being elected president of the Wynyard Football Club and a vice-president of the Wynyard Homing Society. In February 1924 he and an associate were reported to be undertaking successful negotiations with farmers in the Marrawah district, his aim being, apparently, ‘to give the best advantages to primary producers’.[16]

Lorna Britton recalled Elijah and Mark Britton losing a great deal of money by signing up for one of Musson’s schemes, presumably the Primary Producers’ Bank. She believed that they were susceptible to cultured English accents like Musson’s. His sales pitch began by giving Lorna a pair of spurs

which he said had served him well during World War I, when he rode his trusty steed into the thick of battle in France. He said they were spurs of pure silver, but I never used them, and they have since disappeared. What use could I have had for such a cruel method of getting more speed out of poor Old Nag, who did her best with only a twitchy stick as an urge. He was a huge man, and even brought his wife with him on one occasion out through the muddy road astride a pair of horses. He used all the charismatic charm, playing the piano and singing. One favourite was ‘The Mountains of Mourne’, which he sang with such fervour that the mountains really did ‘sweep down to the sea’. He wooed the brothers so they signed eagerly on the dotted line, which cost them a great deal of money, and Mother shed many tears.[17]

Frank Britton at home with a broken arm, 1925.

Frank Britton, nine years younger than Lorna, remembered things a little differently, with Musson driving a big flashy car which, because of the muddy track, could only visit Brittons Swamp in the summer. Musson was, according to Frank,

instrumental in taking Dad down for a lot of money, with a lot of bogus companies. And the old Primary Producers’ Bank of course which was paying interest on current account that Dad never ever said you could ever do. Anyhow they did, and they went broke.[18]

The Primary Producers’ Bank closed its doors in 1931 and was liquidated. By then the fraudster’s schemes were catching up with him. In December 1931 Musson was arrested along with three other men in Texas, Queensland, on a charge of conspiracy to commit fraud by enticing people to invest in the Tasmanian Credits Ltd.[19] The men were convicted, but on appeal their convictions were quashed.[20] There was no escape in 1933, however, when Musson was one of three men arrested in Queensland on charges of conspiracy for selling land to which they had no title in relation to the Texas Tobacco Plantation Pty Ltd of Queensland.[21] The men played on their military bearing, calling themselves Captain Brough, Major Field and Major Musson, although Musson admitted that he had not held the substantive rank of major during World War I.[22] All three were convicted and imprisoned for three years.[23] Frank Britton believed that Musson’s deceit cost him [Frank] an education like the one that his brothers and sisters enjoyed in Launceston and, with it, the chance to become a lawyer or doctor.[24]

[1] Bernard Cronin, The timber wolves, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1920.

[2] Llewellyn Irby to his family from Smithton 27 October 1922 (copy held by the author).

[3] Surveyor-General to Minister for Lands 12 May 1921, ‘Exploration survey Salmon River Wellington’, file LSD344/1/1 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

[4] ‘Welcome Swamp: Royal Commission’s Report’, Examiner, 13 March 1924, p.8.

[5] Mark Britton to Jim Livingstone 11 February 1924, Journal pp.102–06.

[6] Mark Britton, Britton Timbers, to Llewellyn Irby, Conservator of Forests, 11 February 1924, Journal pp.107–10.

[7] Mark Britton, Britton Timbers, to Llewellyn Irby, Conservator of Forests, 19 February 1924, Journal pp.111–12.

[8] Mark Britton, Britton Brothers, to S Moore, Forestry Office, Smithton, 14 October 1925, Journal p126.

[9] Phil Britton, ‘Memories of Christmas Hills (Brittons Swamp): the Story of the Sawmilling Industry and Farming in the Circular Head District 1900–1980’, pp.25–26 (manuscript held by the Britton Family).

[10] Phil Britton, ‘Memories of Christmas Hills (Brittons Swamp)’, p.26.

[11] JJ Dooley, ‘Far north-west’, Advocate, 8 October 1924, p.6.

[12] Mark Britton, Britton Brothers, to the Conservator of Forests 30 March 1925, Journal p.123.

[13] Mark Britton, Britton Brothers, to Garrett, District Forest Officer14 December 1925, Journal pp.127–28.

[14] ‘Men and women’, Advocate, 19 December 1922, p.2.

[15] ‘Primary Producers’ Bank’, Advocate, 6 December 1923, p.2.

[16] ‘Marrawah’, Advocate, 25 February 1924, p.4.

[17] Lorna Haygarth (née Britton) notes 1984.

[18] Frank Britton memoir 16 December 1992 (QVMAG).

[19] ‘Tasmanian Credits’, Advocate, 14 December 1931, p.8.

[20] ‘Tasmanian Credits’, Mercury, 31 May 1933, p.7.

[21] ‘Land in Queensland’, Mercury, 8 March 1933, p.8.

[22] ‘Tobacco Land’, Brisbane Courier, 11 March 1933, p.15.

[23] ‘Land fraud’, Canberra Times, 15 March 1933, p.1.

[24] Frank Britton memoir 16 December 1992 (QVMAG).