by Nic Haygarth | 17/06/23 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian nature tourism history

Tired of Kindling Kindred? [1] Well, here’s the original Cradle Mountain gushfest. The papers of Launceston mountaineer Fred Smithies contain a fictional account of a visit to Gustav Weindorfer’s Cradle Valley tourist resort Waldheim a century ago.[2] The author of ‘A dip into the Waldheim mailbag’ used fictional letters written home from Waldheim by the visitors to describe the events of the fictional trip. The imaginary party consisted of John and Grace Moore, their daughter Mona Moore, their niece Claudia Crane—and a visiting boy named Percy Lane. The author, who had obviously stayed at Waldheim, gushed high-spirited prose to the rhythms of Bob Quaile’s wagonette ride from Wilmot to Waldheim via Daisy Dell, and continued the girlish banter with Weindorfer.

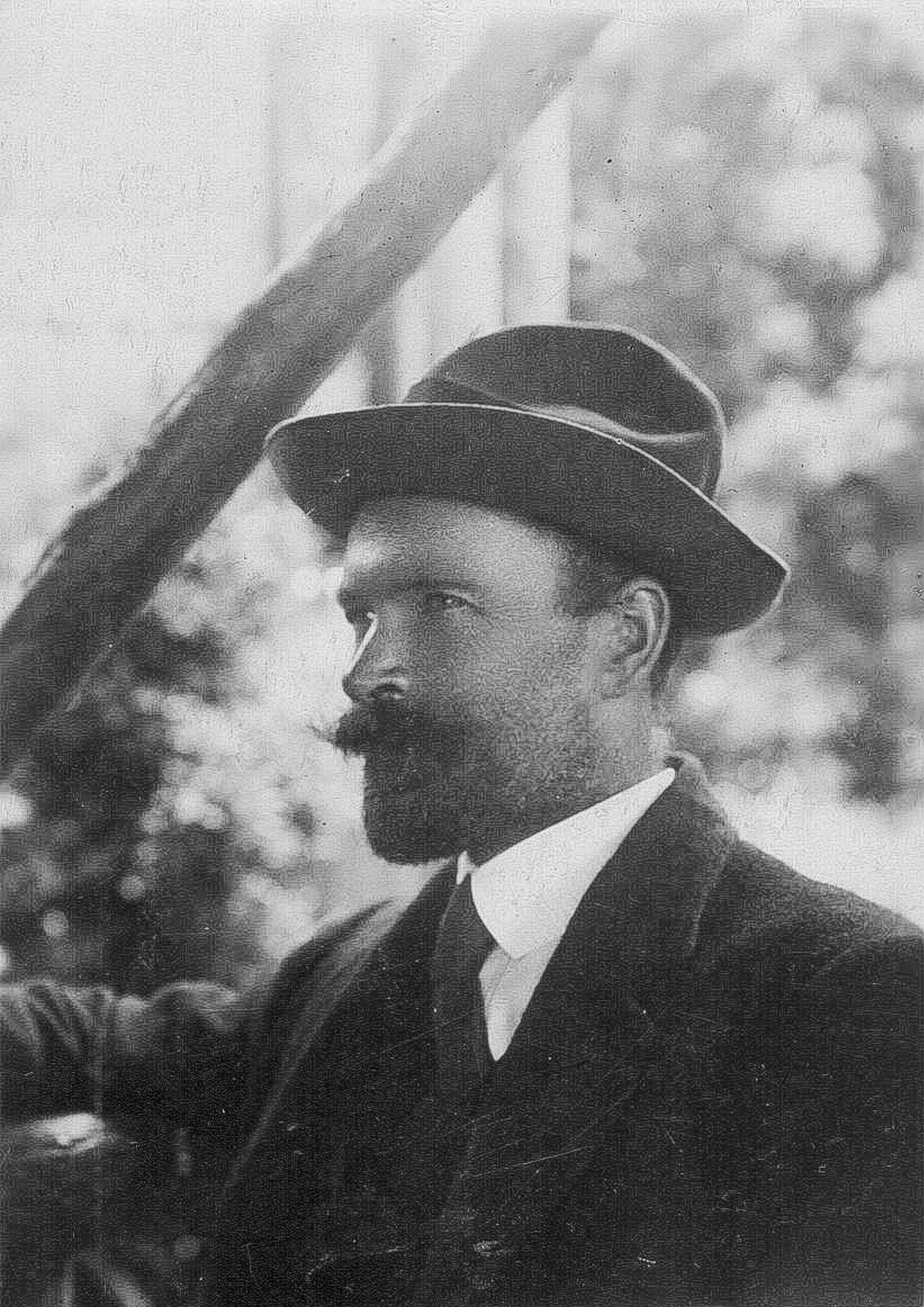

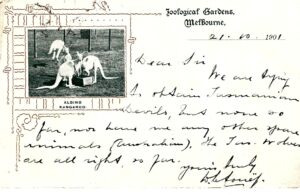

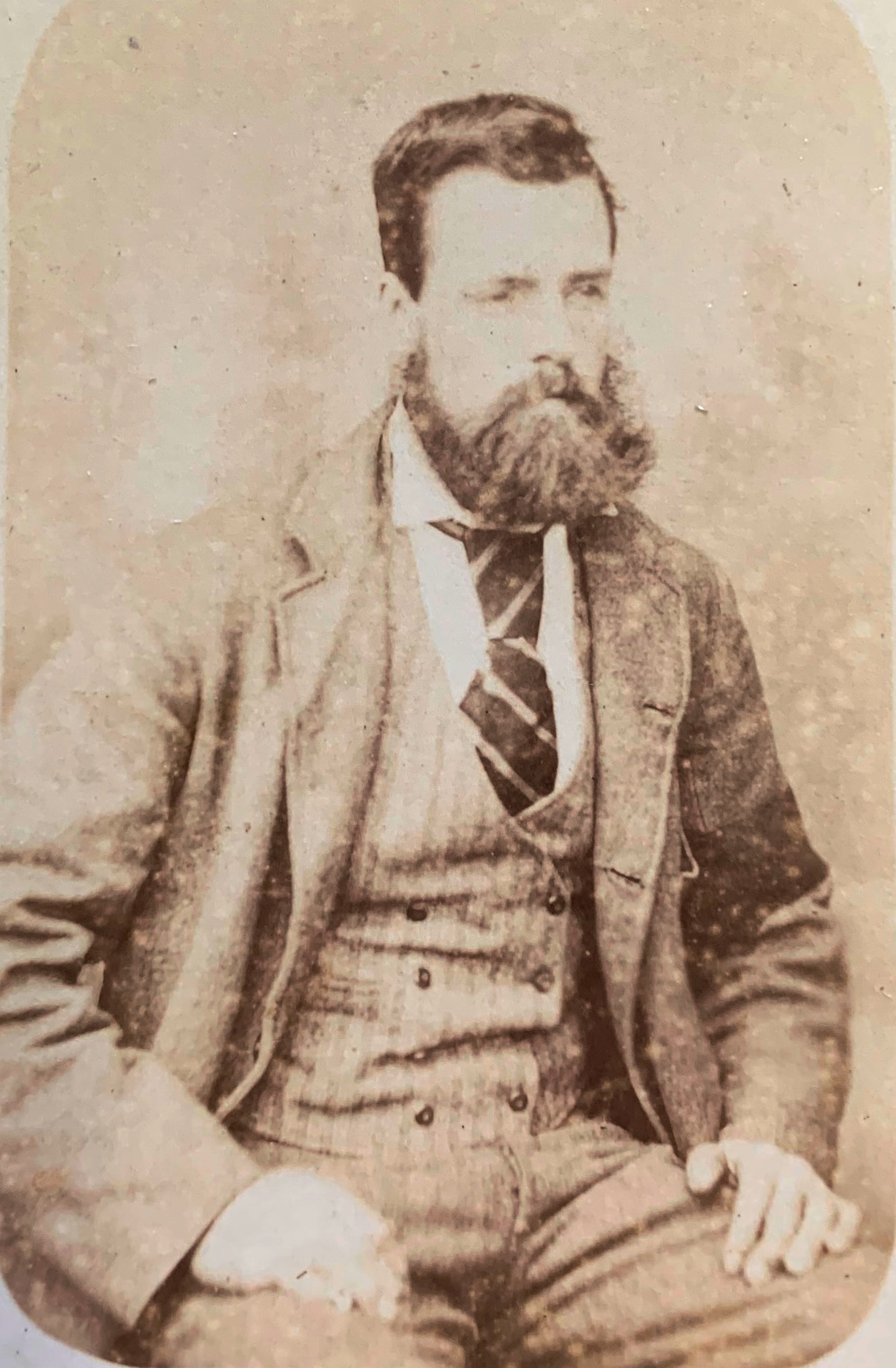

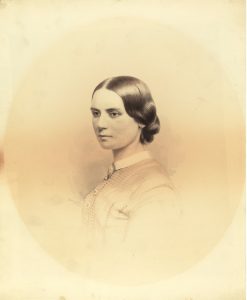

Gustav Weindorfer. Ron Smith photo.

Who was this accomplished author? Many women lost it over the cultured Carinthian immigrant ensconced in his mountain eyrie. In 1923, for example, Weindorfer was snowed in with the scary South African Maude Van der Riet, who later penned an epistle called ‘The Cradle Mountain: a climb to the peak: the world’s view’. The 49-year-old nurse and writer described Weindorfer as

tall and thin like a young cedar tree, with a moustache turned skywards the color [sic] Titian raved about in all his pictures. Mountain air complexion; eyes, what eyes! They flashed like fork lightning on pointed swords …[3]

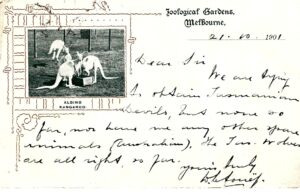

However, it is likely that the mailbag author visited Waldheim earlier, in 1922. The clue is the name Percy Lane, which appears to be an amalgam of two surnames of real people with a Waldheim connection: men called Percy and Lane were working at the Tasman Oil Company’s Barn Bluff shale oil mine. In his diaries Weindorfer recorded Percy and Lane arriving at Waldheim from Barn Bluff on 21 March 1922 and returning to the oil show next day. A Launceston party by the name of Joscelyne was staying at Waldheim at that time, and their day-by-day activities mostly match those described in ‘A dip into the Waldheim mailbag’: arriving on Quaile’s wagonette, then visiting Hounslow Heath, Dove Lake/Mount Campbell and the Cradle Mountain summit.

The names of the Joscelyne party members are recorded in the Waldheim Visitors Book. A poem by Vera M Scott appears as an entry for the period 14–25 March 1922:

A party of five to Cradle Mount came

To visit ‘mine host’, Weindorfer by name

So charming they found him

As they clustered around him

That they marvelled no more at his fame.

They soon settled down to his motto & creed

That ‘nothing else matters’ and ‘of time there’s no need’.

They devoured his puddings with spring water mixed

But after two helpings they found themselves fixed,

And with coffee to follow they had a good feed.

One fine morning they thought up the Cradle they’d climb

Having nothing to do, and plenty of time

So they all started out

With mine host for a scout

The dogs, meanwhile, barking a chime.

The old Cradle frowned down on this frivolous crowd

And said ‘I know well how to deal with the proud.

I’ll teach them to cheek me,

And with lightness to treat me,

I’ll send them home all humbly bowed’.

So they started to climb, arrived at the top,

And the Cradle smiled softly, and said ‘I’ll soon stop

These impertinent mortals

From storming my portals’.

Sure enough they reached ‘Waldheim’ just ready to drop.

Now this party of five had vocations in town

And so, most reluctantly, had to come down

From that land near to Heaven

Of which fun is the leaven

And ‘Waldheim’ itself is the crown.

The visitors book entry bears four other signatures: Lydia Morrison, J [Julius] Norman Piper, HS [Horace Samuel] Joscelyne and his wife HM [Harriet Mary, known as ‘Addie’] Joscelyne née Cumings.[4] All these people were middle-aged but, as Maude Van der Riet had shown, when it came to Weindorfer age did not preclude gushing. Horace Joscelyne was a Trevallyn grocer’s assistant, while Addie managed their house at 26 Delamere Crescent, Trevallyn, Launceston.[5] They had no children. Piper was a soon-to-be-married jeweller in Bourke Street, Launceston.[6] Scott, the visitors book poet, Morrison and Addie Joscelyne seem the most likely candidates for authorship of ‘A dip into the Waldheim mailbag’. It is unknown whether any of them practised as a romance writer, but one of them certainly had the skills to do so.

A picnic photo of Scotts and Cumings: (left to right) Caroline Cumings, AC Jowett, May Scott, Minnie Jowett née Cumings, Addie Joscelyne née Cumings, L Jowett, Wilfred Jowett, HWH Jowett and Henry Sidney Scott. Was Vera May Scott the photographer? LMSS754/1/28 (TA).

Vera May Scott (1886–1962)[7] was born at Battersea, London. At the 1901 British census she was a 15-year-old living in London with her 47-year-old piano tuner father Henry Sidney Scott and 37-year-old Brisbane-born mother May Scott.[8] No record of the family’s migration was found, but in 1922 Vera May Scott was an unmarried typist living at 28 Delamere Crescent, Trevallyn with her parents and sister Eleanor Scott.[9] Scott lived next door to the Joscelynes and had a strong connection to the family. In 1945 she thanked Horace Joscelyne for ‘unfailing kindness’ during her mother’s long illness.[10] Rupert William Joscelyne Hart, whom Scott recognised in her will, was the son of Horace Joscelyne’s sister Violet Mary Joscelyne.[11]

Lydia Morrison (1886–1971)[12] appears to have emigrated from England as a small child in 1891, along with her two-year-old brother and her parents, 28-year-old Lydia Morrison senior and 35-year-old farmer William Morrison.[13] In 1922 Lydia lived with her parents, her sister Dorothy Mary Morrison and brother William Morrison junior, at 211 St John Street, Launceston.[14] Forty-six years later in 1968 Lydia was still listed as an unmarried clerk—at 82 years of age—and living with her bookbinder sister at 6 Union Street, Launceston.[15]

Harriet (‘Addie’) Joscelyne née Cumings (c1872–1946) emigrated from England with her sister as a teenaged nursemaid in 1888. Her parents, Ebenezer and Caroline Cumings, had preceded her and were already Launceston residents.[16] Addie’s older sister Minnie gave her occupation in the passenger list as schoolteacher, and until her marriage in 1893 she operated the Trevallyn Preparatory School.[17] At this point Addie Cumings took over from her, continuing the school until at least 1897.[18] This suggests that she was at least reasonably well educated. Addie Cumings married Horace Samuel Joscelyne at Launceston in 1903.[19]

Tasmania’s great romance novelist of the time, Marie Bjelke Petersen, threatened to pen a Cradle Mountain tearjerker which never eventuated.[20] Given her habitual bible bashing, some may see that as a good thing, but a Bjelke Petersen blockbuster might have done wonders for Weindorfer’s business. It would be surprising if Bjelke Petersen hadn’t pencilled him in as a model for her male lead—like Robert Sticht in her Mount Lyell Mine saga Dusk (1921)—and Waldheim as her anonymous location. Like driver Vic Whyman in her Jewelled Nights (1923), Cradle Mountain coach driver Bob Quaile would surely have appeared under an alias in her new screed. Bjelke Petersen championed Tasmania’s great forests and mountain scenery, and as such may have looked askance at the ‘grass tree’ (Richea pandanifolia) bonfire in ‘A dip into the Waldheim mailbag’.

However, much of the latter text is straight out of the BP playbook. The unknown author’s heroine Claudia Crane even notes ‘I could not help thinking what rich material a novelist might find here’, before listing elements of the region’s romantic history. ‘Why go to other lands for the setting for tales of adventure, of love, and mystery?’ Why indeed? Cradle Mountain was a romance writer’s paradise waiting to be reimagined.

A DIP INTO THE WALDHEIM MAILBAG

From Claudia Crane to an invalid friend.

Wilmot

My dear Margaret,

I am on the eve of adventures strange and wonderful — bound for a lonely chalet in a mountain valley, 2000 feet above the sea level. How does that appeal to your romantic soul, oh! my friend? And, moreover, the said chalet is inhabited by a solitary man, who is cook, housemaid, washerwoman, waiter and guide rolled into one. Poor Aunt Grace is filled with the most dismal forebodings as to the dinners and beds we shall get, but to Mona (who has just turned sixteen) and myself, the prospect is most alluring — the uncertainty — the romance — of it all makes an irresistible appeal. (All the same we hope the dinners are good.)

On arriving we had a hearty welcome from Mr Quaile, a fine white haired, weather beaten old chap with a face like a rosy apple.[21] Mona christened him ‘Daddy’ on the spot and my heart warmed to him straight away as I caught the kindly, compassionate glance that just rested on my crooked shoulders. He led us on the verandah of a funny rather rambling little house and introduced us to the quaint, bright little hostess. When we trooped inside we found the place surprisingly roomy and comfy and we all approved of the cheery fire burning merrily in the open fireplace and straightaway fell in love with the inviting little white beds waiting for us. Now my inner woman having been well satisfied, I am writing this epistle in front of that same fire, with the lovliest [sic] pink lilies smiling down at me from the high mantel.

The little township seems to be a paradise for lilies. This afternoon as we were sitting on the grass in front of the house a lovely slip of a girl passed with a most beautiful cluster of the Golden Lily of Japan nestling in her arms peeping into her sweet oval face. I wonder who she is? She looked nearly as lovely as her lilies. We were favoured with many a kindly curious glance from the passers by [sic] and Mona was highly amused when one passing man called to us ‘You will find it cold up the mountains’.

Ah well that small white bed is calling me, so Good-night.

Yours,

Claudia (in search of adventure)

PS I find that the lovely girl is Daddy Q’s daughter.[22]

C.

Bob Quaile. Photo courtesy of Leslie Quaile.

From Claudia to Margaret.

Dear Margaret,

We left the world behind at seven o’clock this morning, in the most glorious sunshine. Our vehicle was a weather beaten old warrior, and had evidently started life as a mailcoach [sic]. We were inclined to smile at it and our smiles broadened as our driver with a twinkle in his eyes, implored us to be careful of the upholstering, but before our journey ended we had a huge respect for our coach. We set off merrily along a very fine road, of which Daddy Q was very proud. He is evidently a man of many parts and equally at home as councillor, farmer, miner, road-maker, and moreover is no mean conversationalist.[23] He proved quite equal to carrying on several conversations at once, interspersed with various remarks to horses (sometimes with funny results, as for instance when the remark ‘Gee up, Commonwealth Bank’ nearly sent Mona into hysterics.) I had always had a vague idea that drivers of horses used fairly lurid language but, ‘Gee up! You lazy rubbish’! was about the most violent expression we heard — much to Mona’s disappointment. For the 1st time in my life, I found myself passing through mining country. We passed quite close to the ‘Shepherd and Murphy’, and Round Hill mines. Daddy Q also has a claim which he pointed out to us.[24] Further along the road we had quite a picturesque glimpse of a fine herd of wild cattle, grazing on a hillside. Great tracts of the country we passed through had been burnt, and I saw a variety of fence that was new to me —composed of simply of single huge trunks (mostly chared [sic]) laid end to end.

A posed photo of Bob Quaile with two tourists in his wagonette at Daisy Dell. Burrows photo from the Weekly Courier, 15 February 1923, p.21.

I liked the black and white effect. The quick eye of our driver distinguished some of his own cattle among others, and soon the truants were trotting along in front of us. By this time our fine road was left behind and we were passing along what we were assured was a ‘made road’, and nothing to what was in front of us.

We who were facing each other were bobbing and bowing to each other in a most absurd way. But it was a new experience to us and we rather enjoyed it, but nevertheless no-one grumbled when the horses were allowed to leave the ‘made road’ and take their way through paddocks to ‘Daisy Dell’, where quite our ideal dairy maid — fresh, comely and plump — served us with butter, cheese and cakes of the best. The horses were glad of the spell, as the road had been steadily ascending the whole way, and it was a pretty strenuous climb for them. We started once more, this time in a fine drizzling rain, which prevented our getting any of the early glimpses of the Cradle to which we had been looking forward.

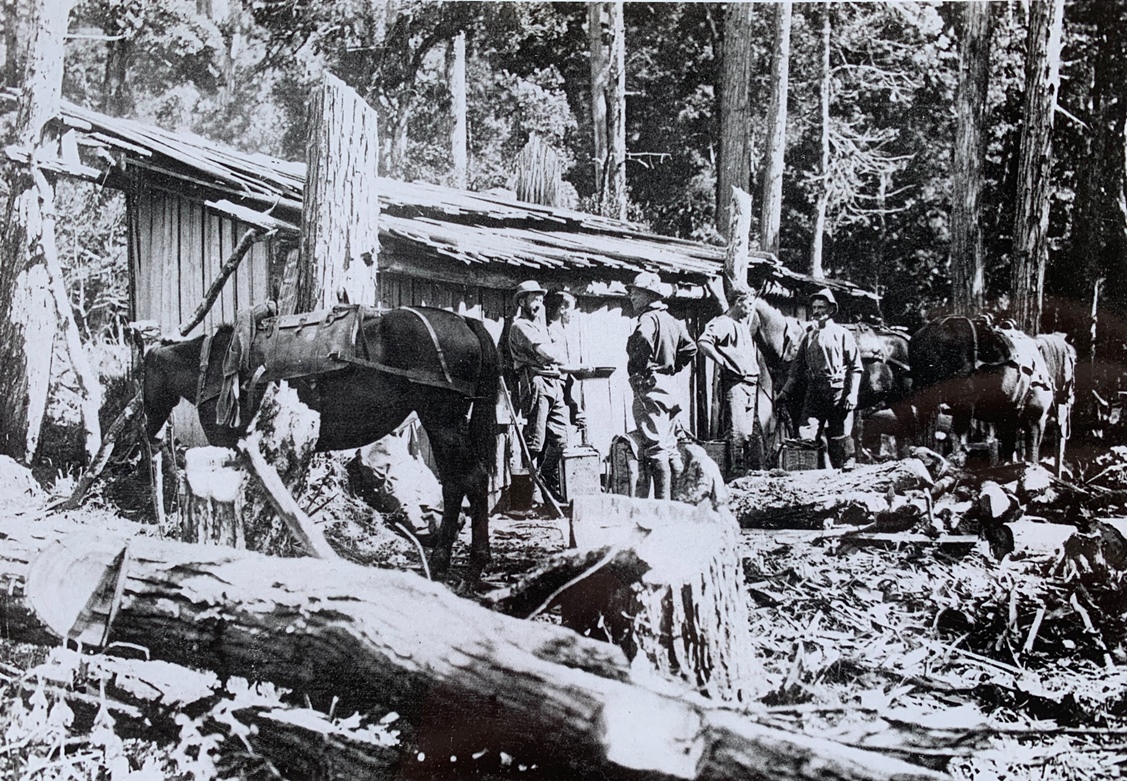

Soon after we had passed Pencil Pine Creek and the Sawmill we came across a gang of men hard at work on the road, and there a halt was called, and our luggage had to be ‘packed’.[25] The girls decided to stroll on in the soft rain, and when the horses caught us up we could not help smiling at the poor pack horse — he looked for all the world like a camel with a huge hump. The decree went forth that we were to ride, to Mona’s huge delight and my inward dismay. But once mounted, I found it delightful to gaze round without troubling what my feet were doing.

The last three miles of our way lay along a lovely little green valley, much of it by the side of the Dove River. The 1st glimpses of our new home came rather unexpectedly, but a very pretty glimpse it was in spite of the rain. Soon we were at the porch and found ourselves welcomed, not by an old man, as we were expecting, but by a big dark-bearded man, in the prime of life.

We were soon lifted from the saddle and walked into the house on rather wobbly legs, to be greeted by a huge fire and a deep barking proceeding from under the couch. The barker proved to be ‘Flock’, a dignified and matronly old dog, who soon came out and made friends with us, together with her son, ‘Flick’ who is, according to his owner, ‘young and silly and spoiled by the ladies’. Our bedroom opens out of the living room and contains 4 bunks. Moss and lichen still clings to the small trees used as posts in the room, also to those supporting the bunks above our heads. The picture frames are of bark trimmed with lichen. The tassel on our blind is a dear little fir cone. The recess for our washstand (which I grieve to say looks uncommonly like a packing case, curtained,) is lighting by a tiny fascinating window made of three old negatives. The seats are merely lengths of tree trunk stood on end. The walls, of King Billy pine, are fine, each plank having a broad white streak running through it where the sap once ran. The rugs on our floor are badger skins, but the star room boasts a real carpet and a leopard skin, head and all.

I am too tired to write more to-night.

Yours,

Claudia.

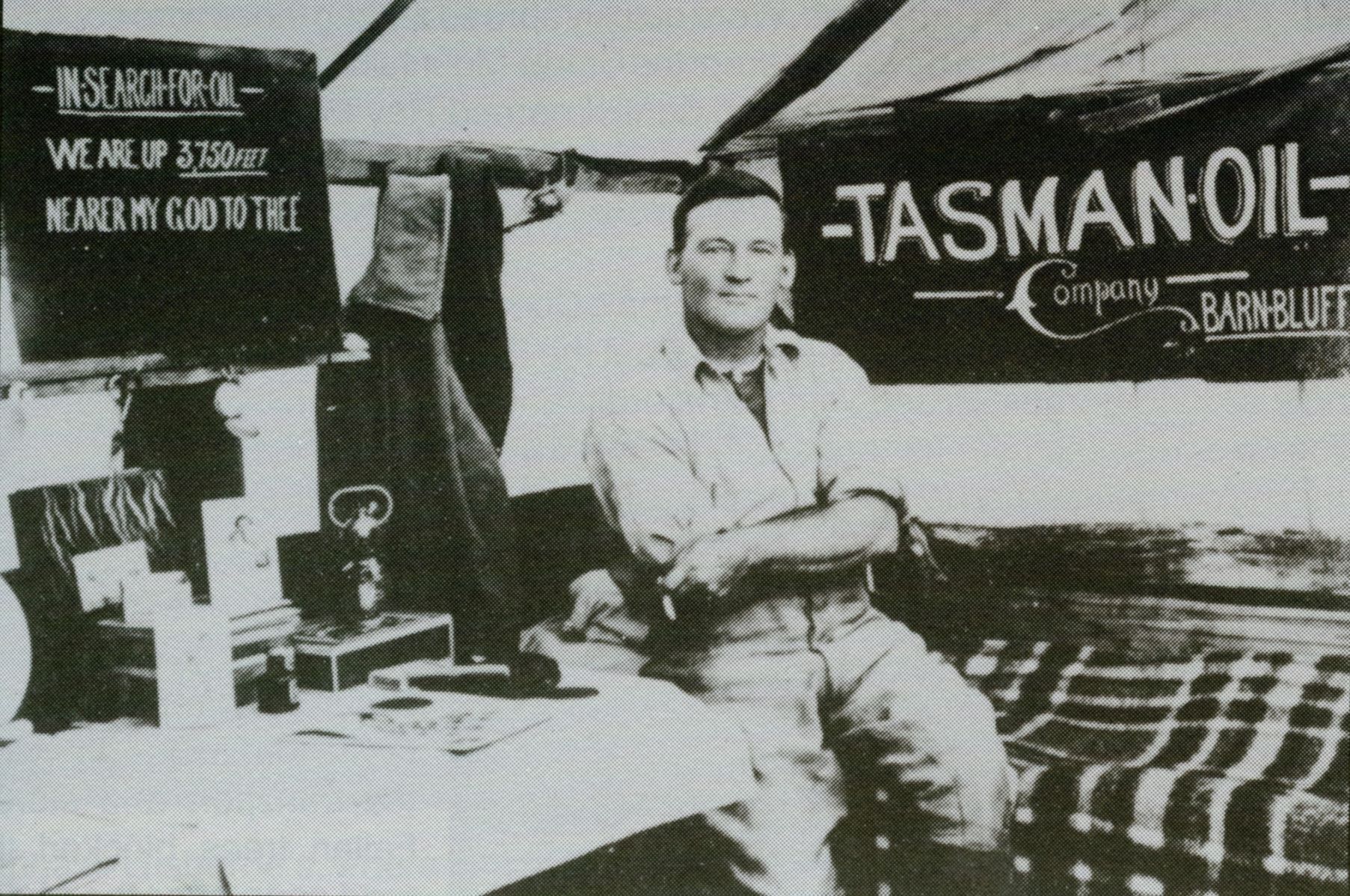

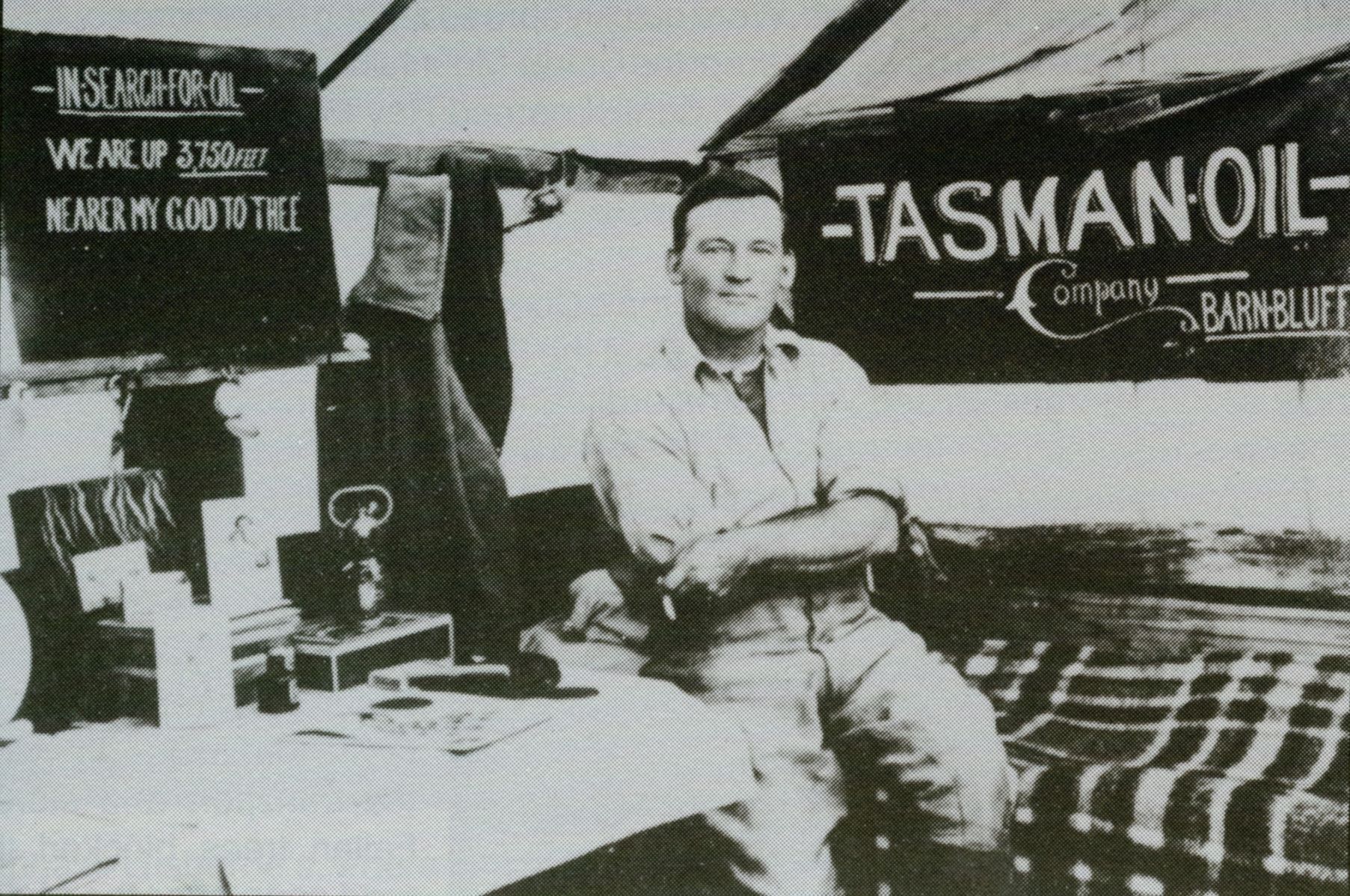

‘Nearer my God to thee’: AG Black, mine manager for the Tasman Oil Company at Barn Bluff, Christmas 1921, with his gun and family photos. Courtesy of the late Es Connell.

Mona to her girl friend [sic].

My Darling Marie,

Such a lovely thing has happened. A perfectly beautiful boy came here yesterday. He has most glorious brown eyes and a lovely big nose like Napoleon. His father and Dad used to be mates. His father is one of the directors in some mine here, and he worried his father till he let him come here to work, but now he is sick of it, and so Mum has asked him to come to town and stay for a holiday and it is such fun having him here, everyone else is pretty old except Claudia, she is a love, but she can’t tear round like I want to.[26] Percy had such a lark this morning. You know Mr W always brings us a cup of coffee before we get up. Well he knocked at the door and said ‘milk for the babies’ like he always does and I got on my elbow ready to take my cup (Claudia always get the tray — a bonza one made out of KB pine). When I looked up there was Percy grinning like a Cheshire cat and he had on the most beautiful silk pyjamas with purple stripes and a silk cord round the waist (Dad says he must be an awful fop to wear silk and he looked beautiful in them). I gave a most awful yell and nearly dropped the cup on the floor and Percy and I just squealed, it was so funny. We made such a row that everyone came trooping in to see the fun until Mum rapped on the wall and they all got for their lives.

Oh! I say Marie, did you know I had pretty ankles? Mr W served out leggings and putties to Mum and Claudia, but he wouldn’t give me any, because he said my ankles were the nicest he had seen for a long time and it was a pity to hide them. I thought perhaps he was stuffing, but he wasn’t because I asked Claudia, and she said it was quite true, she had often admired them. So that’s my first live compliment.

Mum is getting to be quite a sport up here — she doesn’t chip a bit. Every morning she goes out to the Kitchen for the Porridge jazz with the rest of us. We all streak out into the Kitchen like a lot of Oliver Twists and everyone grabs their own Porridge when Mr W puts it out and there is a procession back into the Dining-Room. But no-one ever asks for more, cos he gives us such big platefuls.

I do hate washing porridge pots at home, don’t you? But it is quite easy here the pot just gets stuck out on the roof until next morning and the Porridge comes off without any trouble. And he’s got quite a cute idea for washing windows, he just takes them right out and puts them in the Creek, and both sides are washed at once.

Mum doesn’t even mind getting her feet wet. You know coming out she wouldn’t even let me get out of the Trap to see the Pencil Pine Fall cos it was raining, and I might get my feet wet. But up here they are nearly always wet, and Mum thinks nothing of one foot slipping into a hole with water a foot deep in it. All the wet boots and stockings look so funny dangling round the fire place at night.

That Percy is pulling my hair so I’ll have to go and hammer him now so Ta-Ta, heaps of love.

Mona.

PS I hope you get that little note I sent by pigeon post. It was fun letting him go.

Mr John Moore to Percy’s father.

Dear Lane,

Suppose you will be somewhat surprised to note the address heading this letter — nearly as surprised as I was when your son rode in here. The lad had been sent over from the mine on an errand and was overjoyed to find our party. Truth to tell I think he is beginning to find the mine life a trifle monotonous and a short spell would [do] him no harm. Unless we hear from you to the contrary, therefore, it would give us great pleasure to keep him with us during our stay here and to take him home for a few weeks change. We would be glad if you would drop the manager a line and make this right for him. He and my little girl Mona have become great pals and are keeping all the old fogies alive with their harmless nonsense.

You should really take a spell and run over and see this place next summer. By that time the road will be right through and the accommodation even better than now, as our host has great plans for enlarging and improving the house and will probably have domestic help also.

At the present time he does the whole of the housework and cooking unaided, in addition to this work as guide, but expects the business will become far too large for that to continue possible [sic]. The wife was really rather worried about domestic arrangements, but our host soon proved he understood the important art of cooking a good dinner. On our first day we sat down to roast mutton, potatoes boiled in their skins and an excellent boiled ‘spring water’ pudding the flavouring of which aroused much curiosity among the ladies. As a matter of fact I found that ½ cup of rum was used and we have since had a similar concoction known as Barn Bluff pudding flavoured with port wine. Tip top coffee is the finishing touch to our meals. You will see that we are in no danger of starvation.

The house is unique, built almost entirely by our host. A picturesque porch opens into the dining room, 3 bed-rooms, the kitchen and wood shed open out of that, and one other bedroom out of the kitchen. There is an arrangement of curtains which can be drawn at will round the central part of the dining room to exclude draughts. Two long seats after the style of box couches run each side of the table and at the foot is an extremely solid arm chair cut from a tree trunk. The fire place is one of those huge affairs within which one can sit and is always garnished with a hug back log under which mine host can scarcely stagger. The kitchen is compact enough to be found on board ship and the owner can stand in the middle and reach almost anything he wants. By the way, we men, clad comfortably in pyjamas and slippers start most days in the kitchen with a good old yarn and smoke before the ladies are astir. You would enjoy those yarns. Most of the bedrooms are fitted with bunks, that occupied by my wife and self being the only one with ordinary beds. Our room also boasts a pretty little private balcony which the ladies have christened ‘The Juliet balcony.’ The tent room and the huts are some yards from the main buildings and are furnished with a couple of beds and a fire place with wood-shed attached, the hut having in addition a loft with an extra bed designed to accommodate mine host in times of pressure. The feature of the place however, is the bath room, a hut with its own small verandah standing on the brink of a creek a few yards from the house. Water is supplied from the creek by a most ingenious arrangement and may be heated in the copper which always stands on the huge fire place.

One thing I know will strongly attract you, there is a fine gramophone here, and a first class selection of records and we have enjoyed many a good concert as we sat round the fire after a long day’s tramp.

I should certainly like to come again next summer and possibly you can arrange to join our party then. However, we can discuss that at our next meeting.

Yours faithfully,

J Moore.

Richea pandanifolia in Cradle Valley. HJ King photo courtesy of the late Daisy Glennie.

From Claudia

My Dear Margaret,

I want to tell you of some of our walks. The first was in most glorious sunshine. We crossed the dear little creek that runs past the chalet and followed the steep moss-bordered path that winds up through the gulley [sic]. Here I made the acquaintance of the famous beech which is the only native tree that sheds its leaves.[27] Its slender graceful stem is beautiful and you have no idea how pretty, glimpses of the blue sky, looked through the canopy of little green leaves. I was quite sorry when we came up into the open but when we reached the top of Hampstead Heath we had a glorious view on all sides — the mountains in front and away back the way we had come to Middlesex.[28]

We went for the same walk again later but wandered further away over the hills and had a lovely picnic boiling the billy in the approved bush fashion. It was a delightful sight to see my rather stately Aunt Grace devouring a huge slice of bread and butter on which was spread a tinned herring and enjoying it too.

I think our lovliest {sic] picnic spot was a little pebbly speech on the shores of Dove Lake. The beauty of the spot and even the sight of Cradle frowning down upon us, failed to subdue the irrepressibles, who were madly engaged in getting as much of the beach as possible down each others’ backs. So to keep them quiet we set them to work getting our lunch. Our host had once been busy on that beach making a raft and the pair found too paddles roughly cut out of planks. These they seized and pressed into service as bread board and meat dish respectively. Mona soon had a nice little pile of bread and butter on one end of their respective paddles and solemnly marched round and served the waiting circle.

Soon we found ourselves climbing up the gently sloping sides of Mt Campbell. Half way up, we rested on a lovely fragrant couch of wild thyme[29] —So now I can say ‘I know a bank where the wild thyme grows’ because I do (Talking of resting, in this part of the world — if you want to rest where the ground is wet and it generally is wet, here we find you simply sit or lie on the strong stunted bushes growing about a foot above the ground and you have a seat fit for a Queen.)

As we pushed on up the mountain to our surprise we came across two or three snowdrifts. Of course each one was the signal for a scramble between the children (and I regret to say not wholly confined to them) but soon they came across an even more attractive diversion. Percy found a huge kerosene plant and promptly set fire to it.[30] It was really marvellous the way that green plant blazed and the intense heat it gave. Mona yearned to set fire to everyone she came across after that but her father wouldn’t hear of her spoiling the scenery in that fashion.

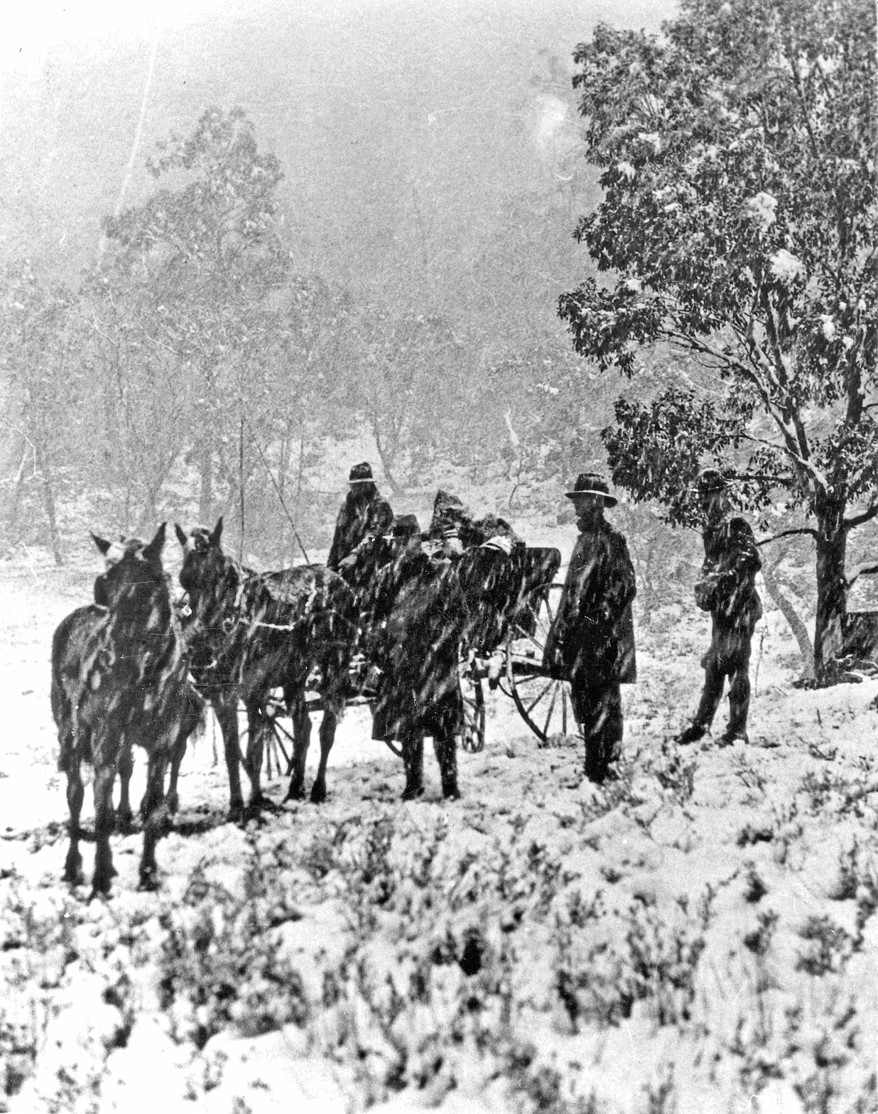

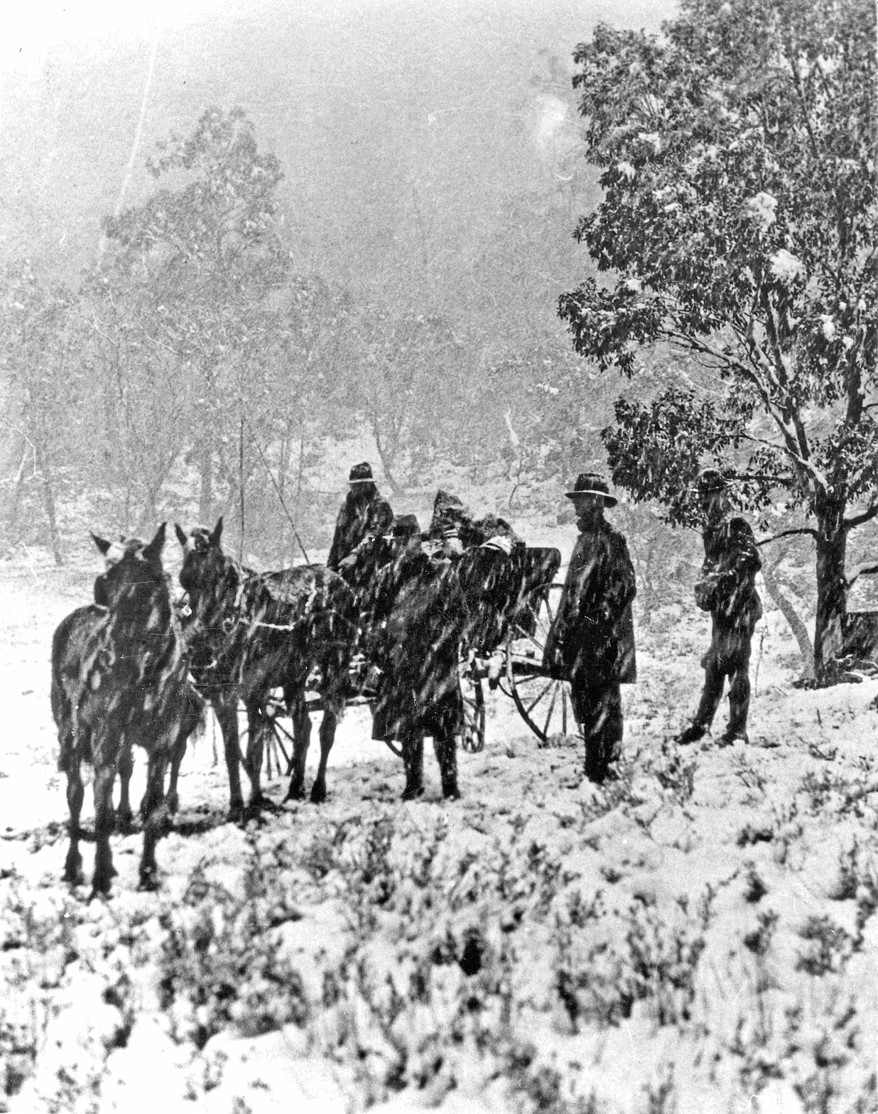

One morning we woke to find all the world white and the chalet a fairy place. We only got occasional glimpses of the Little Horn when her misty veil floated aside for a second, but those glimpses were beautiful indeed. Of course Mona and Percy were just spoiling for a snow fight and her father and I were dragged out to see fair play. At least that is what we intended, but we soon found ourselves involved in the battle and enjoying it mightily. The child’s delight in all was pretty to see, and so was the pride in her father’s eyes as they rested on the glowing face, alight with mischief and triumph as a well-armed snowball slipped down Percy’s neck. Our little Mona will be a very lovely woman some day. Ah me! What would it be to be sixteen and straight![31]

After peace had been declared we struck into the trees above the clear slope which had been the battlefield, and found a lovely little path winding among the trees towards the world. You have no idea how fascinating it is to stroll among the pretty floating flakes of snow. We felt quite injured when presently it turned to rain and sleet — it seemed commonplace. As we turned to retrace our steps Percy begged us to climb a tiny hill that lay between us and the ‘Dove’, directly facing Cradle. So up we climbed and there lay before us the Dove valley, Mount Campbell, the little foothills and Cradle, all one dazzling white vision of loveliness. I have only to shut my eyes and I can see it all once more. I wish you could, you would love it so.

Yours,

Claudia.

Dear Margaret,

It has been wet the whole day through. Mona was roaming restlessly round, poking her little nose into most things, when she came upon a printed notice on the roof ‘Special apartment for naughty girls’. Of course she immediately demanded the history thereof, and there was something very like a twinkle in the eyes of our host as he told the story of two unfortunate girls who had been imprisoned there. ‘And you too shall go up for you are the most naughty of them all’. There was a wild shriek from Mona, a frantic rush to the door, and then ensued such a scuffle as you never did see. When it was all over and Mona was safely in prison Mine host shook his head mournfully as he mopped his heated brow. ‘And she was the heaviest of them all.’ Then there was a shout of laughter for a shower of ancient Bulletins and Couriers came tumbling about his ears from the trap door above and Percy was promptly hoisted up to keep the rebel in order.

It was such evident cruelty to keep those two shut up that Uncle John proposed that we should take them for a walk, in spite of the rain. So off we set with one of the other visitors acting as guide to explore the valley in a new direction. First he led us into a most beautiful bit of virgin forest. Trees hundreds of years old towered above us.

Long ghostly locks of pale lichen hung from many of the smaller ones — I never saw such lovely moss and as I have seen here. Only once have we seen ferns in any of the glades, and those only of a common variety, but the mosses are exquisite. Presently we struck down into the opening and tramped briskly over the springy turf, the children wrangling away as usual.

Presently I made out that Percy was affirming his ability to make a big fire in the rain, and Mona was stoutly doubting.

We came to a little valley dotted with grass trees[32] and Percy stepped in front of a huge fellow, burrowed among the dried leaves around the trunk, set fire to them and waited. We watched breathlessly and soon saw a wicked little flame creeping up the trunk and in among the green leaves, and in a few moments great banners of flame were waving defiance to the rain. When we left, nothing remained of the beautiful green tree but a black smoking stump, and we were warned not to say anything about it on our return, as mine host doesn’t like the scenery spoilt. Neither do I, but all the same I am glad I saw it once.

One misty morning we started for the top of the Cradle. We had been looking forward to seeing the mountain lakes but the heavy mist hid everything. As we stood above what we were told was Crater Lake, occasionally we could see a thin silver line of foam, the mist would part for a second, allow us one weird glimpse of the lake then blot it out once more. By the time we had got within ¼ mile of the mountain’s foot the mist had turned to a fine thick rain, and the wind was icy, so a council of war was held and we decided to turn homeward by another route. In spite of the discomfort we enjoyed the experience — it was entirely new to us. It really was extremely funny to be tramping along in the fine rain and not worrying in the least, an inch of cold water swishing about in our boots, our faces perpetually washed but never dried, and drops of water hanging from brows, lashes, hair, chin — in fact anywhere they could cling. It is so strange to shut one’s eyes and fell the cold fringe of wet eyelashes. It was weird too, to look back and see mysterious indistinct figures, some armed with staves, looming in the distance. However we were soon safely home, into dry clothes, and grilling over the big home fire the chops we had expected to grill at the mountain’s foot.

Bed-time now so good-night.

Yours,

Claudia.

My Dear Margaret,

We had blackberry jam for tea, and it started us speaking of the occasional blackberry brambles we passed on our way here always beside a little stream, then someone said they had sprung up from seeds from blackberry jam used by prospectors camping there. Being in a dreamy mood I started picturing to myself the scenes round those camp fires — the rough hard faces lit up by the fitful flames, and from that I fell to musing over the glimpses we had had of lives so different from our own and the unexpected traces of history across which we had come. I could not help thinking what rich material a novelist might find here in the rough life of the mining settlements scattered among the hills — the lonelier camps away back in the mountains — the sawmill at Pencil Pine — the pioneer gang pushing their road into the mountains — the exciting rounding up of the magnificent wild cattle — the old life of the VDL Coy at Middlesex — the oldtime Governor [sic] who visited there — the convicts who toiled up the mountains laden with timber for the observation posts — the stalwart foreigner in his lonely chalet with its mysterious trap doors — the weather-beaten old man-councillor, — farmer, roadmaker [sic], miner, — his slender daughter with her sweet oval face and her hands full of golden lilies — or as we saw her later clad in rough trousers and boots for her work in the farm yard — her lover slipping along in the dusk to give her a helping hand. Why go to other lands for the setting for tales of adventure, of love, and mystery?

My dear! I have inflicted a screed on you. But we go home the day after to-morrow — that must be my excuse. Soon this freer and easy life — where ‘time is not [important] and nothing matters’, the porridge jazz, the wash up symphony, the picnics enlivened by the gambols [sic] of Flick and Flock, Mona and Percy, the fireside evenings of music and pleasant talk, the eagerly looked for coming of Mr Quaile with letters and papers, the meetings with visitors will be things of the past.

However often we come here in the future it will never be under quite the same conditions, and I am so glad we came before things are made too easy and ordinary for us.

Claudia.

MY DEAR MARGARET,

There is a touch of novelty about this letter. It is being written at the foot of Cradle — just as we started out I stuffed some paper and a pencil into my pocket in case I had a chance to write a line. We are just back from the summit and are resting before returning home. It has been a perfectly glorious scramble and I have enjoyed every minute of it. When we stood at the foot and looked up at the strange rugged pile I wondered if I could do it, but it turned out to be fairly easy. As we ascended our guide led us to the opposite side of the mountain and I felt a pang of disappointment as he began to go down, because I could see higher peaks above us. But it was only for a moment and then he began to ascend once more, passing over the lovliest [sic] little green velvety moss carpets. The view from the top is magnificent, we seemed to stand in a centre of ever widening circles of mountains. It was strange to stand on the cairn of tree trunks which we were told had been hauled and built up by convicts and think of the hard toiling hands that had placed them there, and to look at the wonderful view and think of the bitter, unhappy eyes that have gazed upon it before ours.

The scramble down gave us plenty of exercise and our hands were quite as useful as our feet; at the foot, one after the other down we went on hands and knees to drink from a tiny stream flowing from the hillside, and never was water sweeter. Mona seems pretty tired — don’t know what she will be like when we get home — she and Percy have been in such wild spirits that they have covered six times as much ground as anyone else. You know there is a lake on the way named after a Launceston lady,[33] and Mona was much taken by it and has been looking for something to which to tack her own name ever since. Well, she and Percy were for once walking quietly along conversing amicably when suddenly there was a wild shout and Percy darted off and began dancing wildly round a shallow swampy pool. When the rest of us came up he just gasped out ‘Mona’s Marsh’ and took to his heels with the indignant Mona after him like a deer. However she is quite happy now for a certain tiny muddy pool on the tableland bears the legend ‘Percy’s Puddle’ printed in big wobbly letters across its muddy bosom.

Claudia.

PS And oh, the lakes and the mountain are beautiful in the sunshine, but I am so glad we saw them first in their weird misty mood. C.

The Honeymoon Islands at the southern end of Dove Lake, with Beulah Hills on a pine driftwood and kerosene tin raft. Stephen Spurling III photo, 1922 (QVMAG).

My Dear Margaret,

It is 2 o’clock in the morning and I am sitting up in my bunk writing this by candlelight. I am far too happy to sleep so I will tell you of the wonderful thing that has happened. Mona was quite knocked up when we got back [from] Cradle and so it happened that I did not see the arrival of some new guests. I was busy putting her to bed and stayed with her till she was fast asleep. Then I slipped out to the group by the fire. Most of the men were so deep in the discussion of some mining affair that they did not notice me — all but one, quietly smoking and listening, on the edge of the group. He looked up and my dear! It was Dick! How long we stared at each other I do not know, nor how much of the wild gladness at my heart found its way into my face. But presently very quietly he rose, slipped back the curtain and drew me to the porch outside and oh my dear! Such a tangle of mistakes and misunderstandings we cleared up! All the happiness I ever dreamed of is mine. I know how glad you will be. And I am to be married to-morrow — no! It is to-day — I got into a panic at the bare idea but [Dick] only laughed at me and would have his way.

Yours Claudia,

(in a maze of happiness)

MRS JOHN MOORE TO HER SISTER.

My dear Mary,

The most unheard of thing has happened. Here we are at Wilmot and have left Claudia behind at that outlandish place. On our last night there John and myself happened to be left alone round the fire, when Dick Grey walked into the room and calmly asked John’s consent to marry Claudia next day.[34] He had turned up here early in the evening. Really for a moment I could only gasp. It appeared he met a parson staying at Daisy Dell as he came through and as it was bright moonlight, he proposed riding there at once, and bringing him here in the morning. I was really upset at the insane idea and as soon as I found breath enough I started straight for Claudia’s room. There she was, sitting on her bunk in the dark, ‘Claudia Crane, are you mad’? I demanded. When I had got the candle alight I could only gasp again. The little pale face was transfigured — flushed and smiling and sparkling the big eyes soft and shining. At sight of the radiant happiness shining in those eyes my irritation fell away like a garment. I did try to persuade her to come back to town and have a proper wedding but she was softly obstinate, she didn’t seem to think it mattered in the least that she had no trousseau or engagement ring or anything. And after all did it? As she had no relative nearer than ourselves, and we were all here, they were both old enough to be sure of themselves and they had wasted so much time already.

‘Starting for home from the Old Dump’, Bob Quaile at the reins of his horse team as he prepares to return a Waldheim party to Wilmot, 1925, with (left to right) Charlie Monds, Ron Smith and Gustav Weindorfer standing. Fred Smithies photo (TA).

Why should they wait longer? So I had to give in, for after all I had not the slightest right to object. When Mona heard the news in the morning, she was wild with excitement and promptly took charge with all girl’s delight in a wedding. She insisted on doing the thing properly, invited herself to be bridesmaid, and Percy to be the best man, hunted out the one soft little white frock Claudia had with her and fixed up a big tulle scarf of mine for a veil. A wreath of ginsen flowers and sweet scented white daisies nestled in the soft hair, holding the veil in place. My tender-hearted little girl had carefully draped it so that the slight deformity about which Claudia is so sensitive, was scarcely apparent. She had even a bouquet of lovely white berries she had found growing near the house. They were married out on the porch facing the mountain. Even to my eyes the little bride was as sweet as a rose, and it did my heart good to see the rather quiet face of her groom light up at sight of her and to see his eyes grow infinitely tender as they rested on the shy winsome face and I wish you could have heard the serene confidence in the low voice of the bride. After a gay little wedding breakfast, with one of Mr W’s huge slabs of cake in the place of honour, we started for home. It was quite in keeping with the rest of the up-side-down [sic] proceedings that we should be the ones to go (to the strains of the wedding march our host put on the Gramophone) leaving the bride and groom behind for their honeymoon and I am afraid they were not quite as sorry to see the last of us as they should have been — if they were the content in their faces belied them. I am afraid you will be inclined to blame me for lack of firmness but really I do not see how I could have acted differently.

Your affectionate Sister

Grace.

[1] Kate Legge, Kindred: a Cradle Mountain love story, Melbourne University Press, 2019.

[2] NS573/1/1/11 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA).

[3] Maude van der Riet, ‘The Cradle Mountain: a climb to the peak: the world’s view’, Daily Telegraph, 15 December 1923, p.9.

[4] Waldheim visitors book, vol.1, 1991:MS:0004 (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery).

[5] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of Launceston West, 1922, p.31; entry for Harriet Mary (Addie) Cumings, Launceston Family Album, written by Lesley Morgan Blythe and Marion Sargent, https://www.launcestonfamilyalbum.org.au/detail/1030945/harriet-mary-addie-cumings, accessed 10 June 2023.

[6] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of Launceston West, 1922, p.43. Piper married Ada Letitia Isabel Scott, unrelated to Vera May Scott, in 1923.

[7] Years are from headstone, Carr Villa Memorial Park, Launceston; plus 1901 British Census as below.

[8] British Census, 1901, Administrative County of London, Civil Parish of Heathorn, p.22 (accessed through Ancestry.com.au).

[9] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of West Launceston, 1922, p.48. See also will of Henry Sidney Scott, in which he made his daughter Vera May Scott his sole executrix and beneficiary, will no.18727, AD960/1/56 (TA).

[10] ‘Thanks’, Examiner, 23 October 1945, p.2.

[11] See will no.43508, AD960/1/94 (TA).

[12] Years are from headstone, Carr Villa Memorial Park, Launceston.

[13] Passenger list for the Orana, October 1891, Series BT27, British National Archives (accessed through Ancestry.com.au).

[14] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of Launceston Central, 1922, p.34.

[15] Electoral roll, Division of Bass, Subdivision of Launceston Central, 1968, p.16.

[16] Descriptive list of immigrants, ss Coptic, arriving in Hobart 27 July 1888,. CB7/12/1/12–13, p.40 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?s=harriet+cumings&searchTarget=library&qu=harriet&qu=cumings, accessed 10 June 2023.

[17] ‘Current topics’, Launceston Examiner, 13 May 1893, p.5.

[18] See, for example, ‘Education’, Launceston Examiner, 4 January 1893, p.2; ‘Educational’, Daily Telegraph, 21 January 1896, p.4; ‘Diamond jubilee’, Launceston Examiner, 15 June 1897, p.6.

[19] Married 21 January 1903, registration no.608/1903, at St Paul’s Church, Launceston (TA).

[20] Gustav Weindorfer to RE Smith, 20 March 1920, NS234/17/1/4 (TA).

[21] Bob Quaile (1862–1942) was a well-known Wilmot identity, whose farmhouse just north of the village remains today as a barn. Quaile did much to open up Cradle Mountain as a tourist destination. For many years he operated a horse and wagonette service to Waldheim which was Gustav Weindorfer’s lifeline, the trip being broken at Quaile’s halfway house Daisy Dell. Quaile was a Kentish councillor and member of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board.

[22] In 1922 Quaile had only one unmarried daughter, Sarah Ellen Quaile, born in 1897 and therefore 25 years old at the time of the Joscelyne party’s visit to Waldheim.

[23] Quaile was not a miner but had shares in the revamped Great Caledonian Gold Mine at Middlesex.

[24] The Great Caledonian Gold Mine.

[25] The FH Haines sawmill was on the site of the present-day Peppers Cradle Mountain Lodge.

[26] That is, Percy Lane’s father was involved in the Tasman Oil Company mine at Barn Bluff.

[27] Nothofagus gunnii.

[28] Claudia is describing the track through what is now known as Weindorfers Forest to Hounslow (not Hampstead) Heath. Weindorfer’s track was later replaced by the present track in that direction, cut by Lionel Connell and his sons.

[29] Lemonthyme (Boronia citriodora). It has a strong scent which some liken to that of lemon.

[30] Several Tasmanian plants seem to have borne the colloquial name ‘kerosene bush’ because of their flammability, but here the author seems to be referring to Richea pandanifolia.

[31] Claudia refers to her physical form rather than her sexual orientation!

[32] Richea pandanifolia.

[33] The ‘lake named after a Launceston lady’ is Lake Lilla, named by Stephen Spurling III after his sister in 1905.

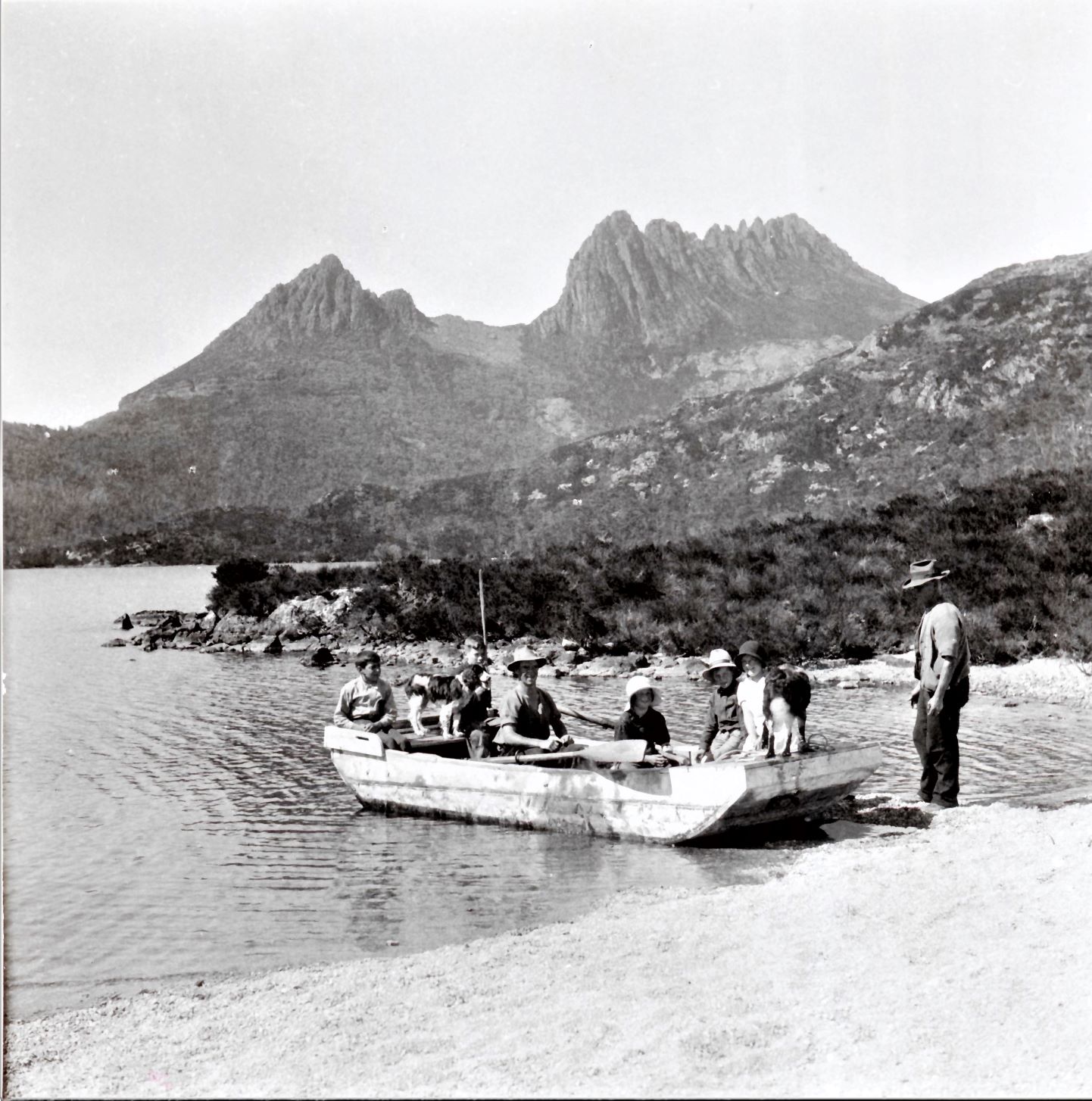

[34] The idea of a Waldheim wedding was perhaps inspired by the legend of the naming of the Honeymoon Islands in Dove Lake. Weindorfer is meant to have rowed a couple to this improbable honeymoon spot, serenading them as he dipped the oar.

by Nic Haygarth | 08/06/23 | Uncategorized

Mining in a scenic reserve? A fur farm as well? How about damming a protected lake to generate power? Bring it all on. During its first 25 years the Cradle Mountain–Lake St Clair National Park was a free-for all.

The national park might have been sparked by a sermon on Cradle Mount but its implementation was more like a meditation on patience. In the 1920s economy reigned over ecology in Tasmania. With the state considered an economic basket case, government had little appetite for funding national parks or for standing in the way of resource exploitation. The Scenery Preservation Board which nominally managed the park had only advisory powers and was, as Gerard Castles suggested, ‘handcuffed’ to this development ethos.[1] Voluntary park administrators attacked their task with a passion. However, their efforts were clouded by conflicts of ideology and pecuniary interest. The first two decades of park management were beset with challenges from the mining, fur and timber industries and the government mantra of hydro-industrialisation. Even the local experts employed to build, maintain and oversee park infrastructure and guide tourists were ‘exploiters’—fur hunters and mineral prospectors. The idea of a road from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair was entertained on the ‘bigger, better and more accessible’ social justice principle that has been used time and time again in Tasmania to justify development of natural assets. What a mess!

Waldheim in the Weindorfer era. Fred Smithies photo, courtesy of Margaret Carrington.

Getting to Cradle Mountain in 1924, the Citroen-Kegresse prototype, which Weindorfer called the ‘platypus motor’. Stephen Spurling III photo.

Origins of the park

The Cradle Mountain–Lake St Clair National Park had three starting points: Cradle Mountain, the Pelion/Du Cane region, and Lake St Clair. At Cradle Valley Gustav and Kate Weindorfer established a tourist resort called Waldhiem in 1912. The story of how they built it and almost no-one came has been told a thousand times. In the Pelion/Du Cane region hunter/prospector Paddy Hartnett had a network of huts, some of which doubled as staging posts for his guided tours as far south as Lake St Clair. Three industrial-size skin drying sheds which stood near Pelion Gap, at Kia Ora Creek and in the Du Cane Gap give some idea of the scale of hunting operations before and after World War One (1914–18). Hartnett’s Du Cane Hut remains today. Lake St Clair had been visited fairly regularly by Europeans for almost a century. It was effectively reserved in 1885 when a half-mile-wide zone around its shores was withdrawn from selection. The Pearce brothers built a government accommodation house, boat house and horse paddock at Cynthia Bay 1894–95 but the buildings were destroyed by fire in 1916.

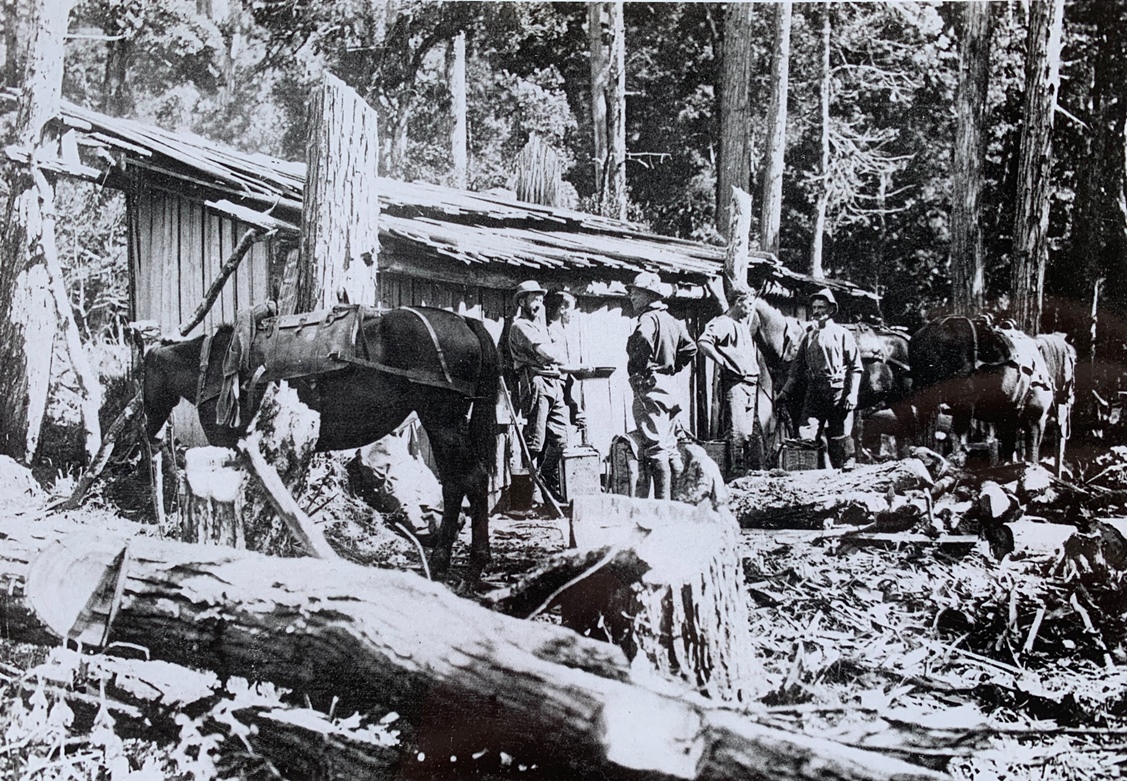

Paddy Hartnett’s massive skin shed near Kia Ora Creek, 1913. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

When Gustav Weindorfer declared famously that ‘this should be a park for the people for all time’, he meant only the Cradle Mountain–Barn Bluff area in which he later operated. Other park proponents, including Director of the Tasmanian Government Tourist and Information Bureau ET Emmett, and bushwalker photographers Fred Smithies, Ray McClinton and HJ King, were familiar with a much greater area. They wanted to include the swathe of land from Dove Lake to Lake St Clair, making an area about six times the size of the Mount Field National Park.

The Scenery Preservation Act (1915), under which the Freycinet Scenic Reserve and National Park (Mount Field National Park) were gazetted in 1916, forbade the lighting of fires, cutting of timber, shooting of guns, removal or killing of birds and native or imported game and damage to scenic or historic features on reserved land. The Act therefore effectively forbade hunting but it did not expressly forbid mining, even though mining always included the lighting of fires and cutting of timber. Parts of the proposed national park area were already logged, grazed, hunted and mined, and to allay fears of these primary industries being locked out of a proclaimed reserve, in 1921 the Act was amended to allow exemptions from the provisions of the original Act.[2]

Stephen Spurling III photo, from file AB948/1/225, Tasmanian Archives.

The Pelion oil field

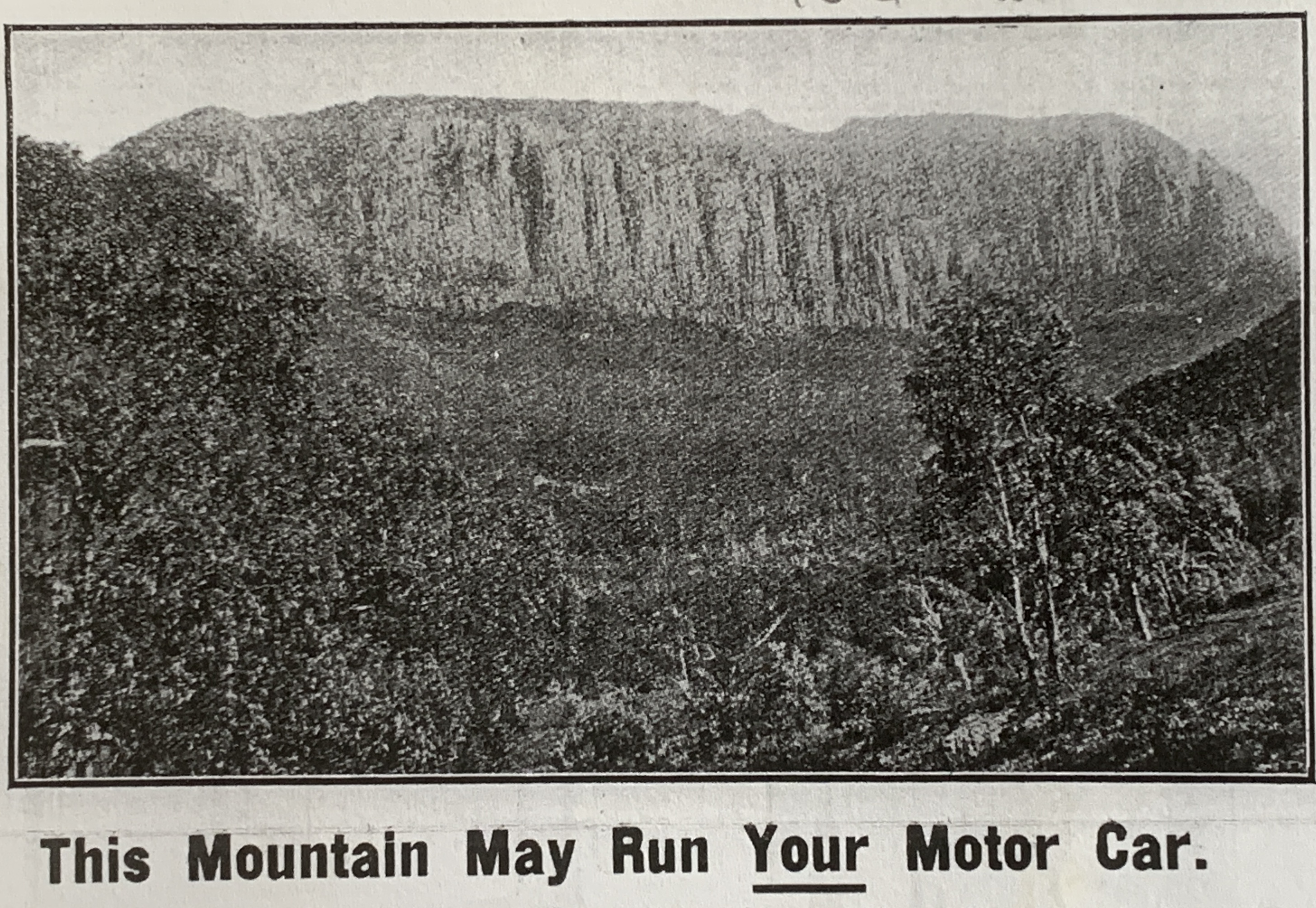

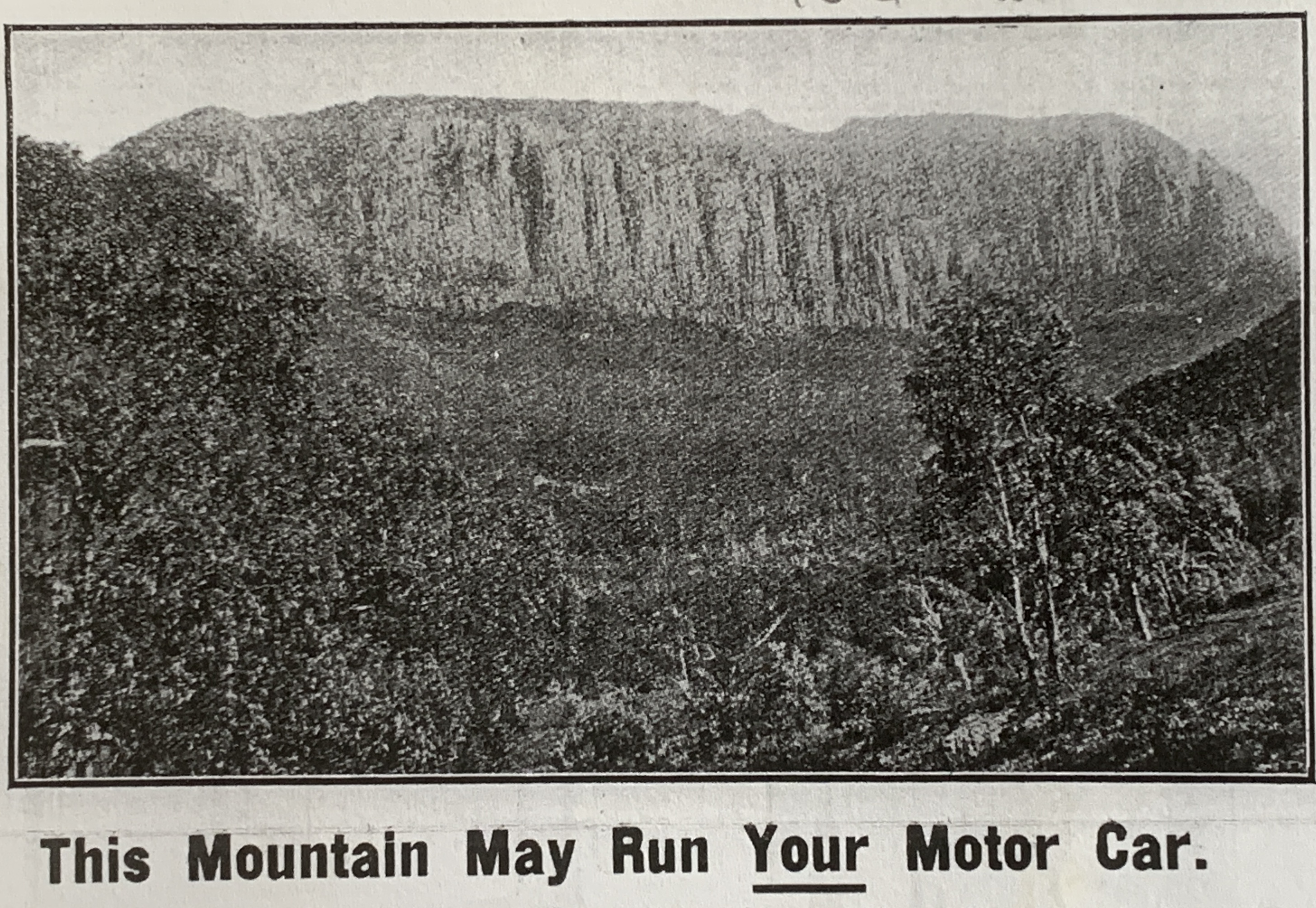

World War One (1914–18) had created anxiety about resource security in Australia and precipitated revolution and civil war in Russia. Outcomes for Tasmania included the search for shale oil reserves and a boom in the Tasmanian fur industry, with brush possum skins helping to make up for the loss of Russian fur reserves. While a lantern lecture campaign promoted the idea of a Cradle Mountain national park in 1921, about 80,000 acres of the land in question was under exploration lease in the search for shale oil (‘inspissated asphalite’). The Adelaide Oil Exploration Company used a Spurling photo to push the idea that Mount Pelion West was a motor oil bonanza. Its proponents assured would-be investors that its lease contained ‘the greatest potential amount of wealth hitherto controlled by any one concern in the British Empire, and, probably, in the whole world, outside the United States of America’. Faith might be able to move mountains, but the government geologist assured them it couldn’t put oil in these mountains. The only lasting impact of oil exploration was the Horse Track south from Waldheim, which was marked to enable pack horses to supply coal/oil operations at Lake Will.

Gustav Weindorfer hunting at Lake Lilla with his dog Flock, 1922.

Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

The Cradle Mountain fur farm

The Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair Scenic Reserves were gazetted under the amended Act in 1922 but at first neither was a fauna sanctuary under the Animals and Birds Protection Act (1919). With the surge in hunting it was inevitable that fur farming on the Canadian model was proposed for Tasmania. The Fur Farming Encouragement Act (1924) reserved 30,000 acres at Cradle Mountain for a fur farm, but before local hunters could protest, in 1925 this area was dismissed as unsuitable by two of the scheme’s proponents, Melbourne skin buyers who, extraordinarily, believed that ‘furs grown at a high altitude have not the good texture of those grown on the low lying country’.[3] Nobody seems to have counselled Tasmanian hunters that high country furs were inferior. Working at Lake St Clair in the winter season of 1925, Bert Nichols reportedly made the small fortune of £500, his possum skins fetching 17 shillings 11 pence and his wallaby skins more than 12 shillings each at the Sheffield Skin Sale.[4] This was at a time when the average annual wage for a farm worker was about £110 to £125.[5]

Two subsidiary management boards

Two subsidiary bodies were appointed to advise the Scenery Preservation Board on matters relating to the two adjoining scenic reserves. One, the National Park Board, already helped manage the Mount Field National Park. Chaired by botanist Leonard Rodway, with Tasmanian Museum director Clive Lord as its secretary, it now added the Lake St Clair Scenic Reserve to its purview. The other body, which administered the Cradle Mountain Scenic Reserve, was created from nominated representatives of interested organisations and municipal councils plus several people who had campaigned for the reserve’s creation.[6] Ron Smith (Cradle Mountain Reserve Board secretary from 1930) and Fred Smithies became standard bearers for the 68,000-acre Cradle Mountain Reserve, but their simultaneous ownership of land at Cradle Valley inevitably led to a conflict-of-interest situation.

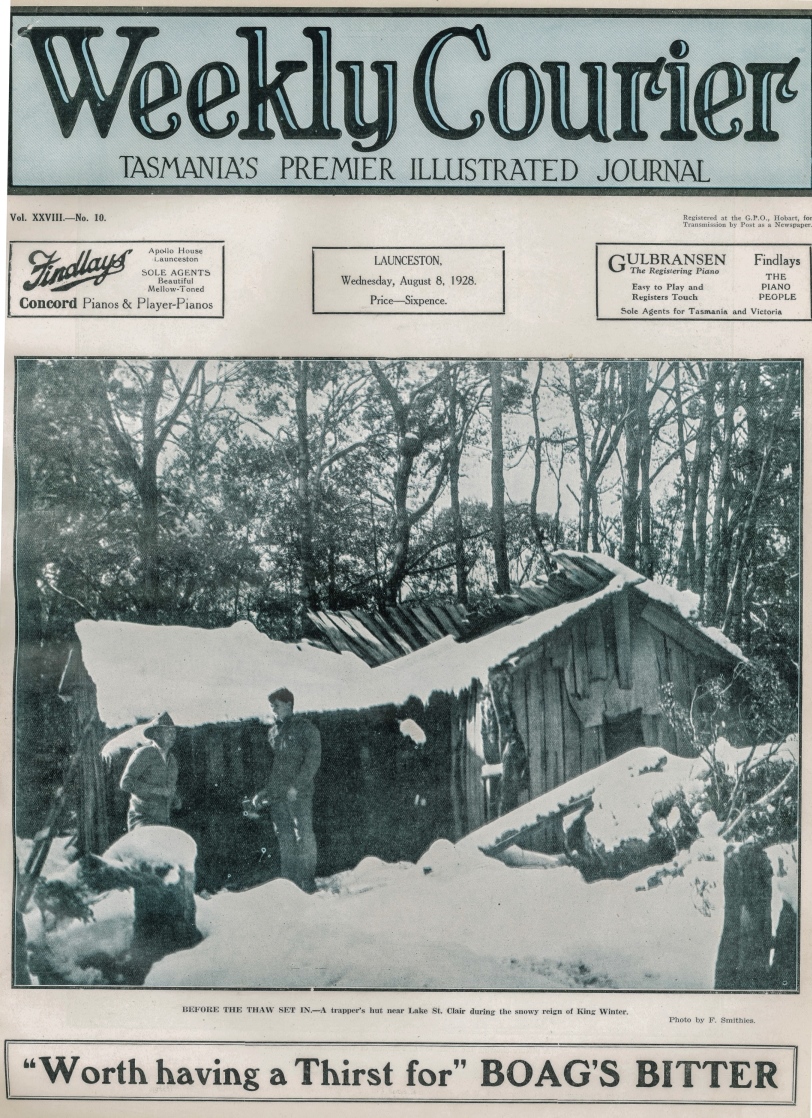

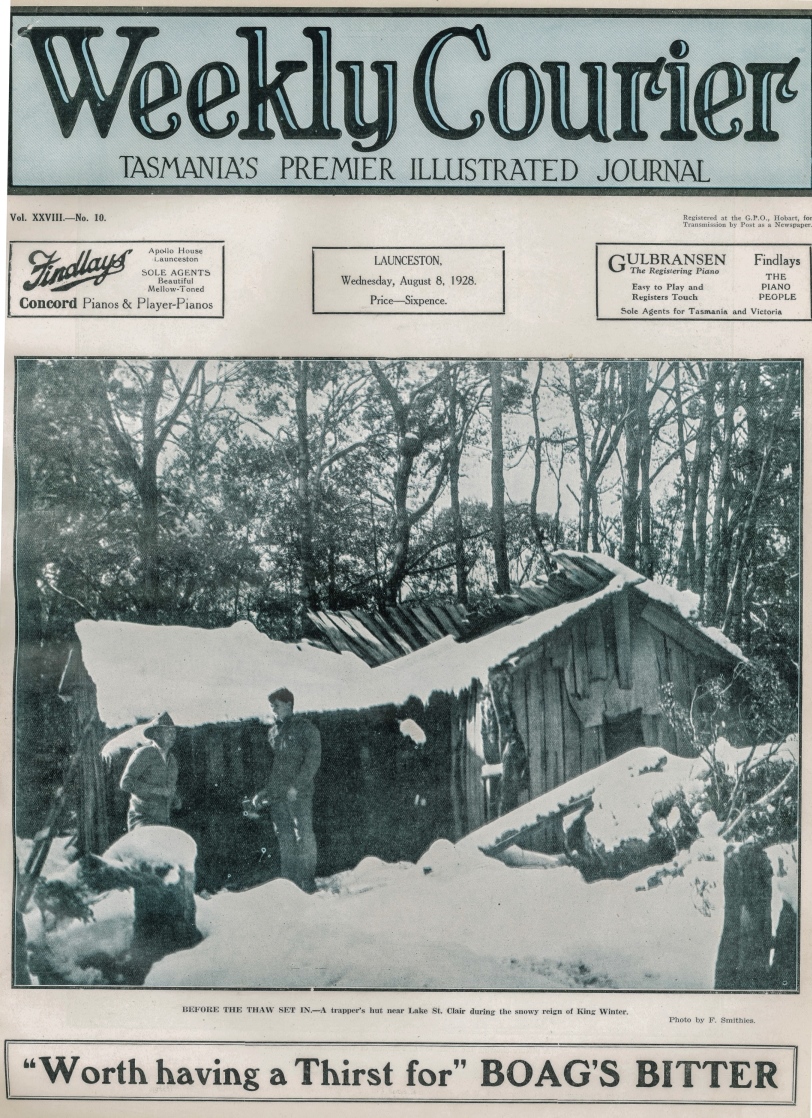

Fred Smithies’ photo of ‘a trapper’s hut near Lake St Clair’,

Weekly Courier, 8 August 1928. Courtesy of Libraries Tasmania.

During 1927 the Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair Scenic Reserves were gazetted as fauna sanctuaries.[7] Two months later the hunter/prospector Dick Nichols was nabbed for poaching at a hunting hut in the Cuvier Valley. His brother Bert was probably around somewhere too but escaped detection, and it became clear that they had a network of hunting huts around Lake St Clair and in the Cuvier Valley.[8] Fred Smithies, a member of the CMRB, was used to sleeping among the drying pelts in Bert Nichols’ Marion Creek Hut.[9] In the winter of 1928 he took a lovely photo of it under snow and this poacher’s hut in a fauna sanctuary made the front cover of the Weekly Courier newspaper![10] Nichols later duplicated the hut for the use of Overland Track walkers.

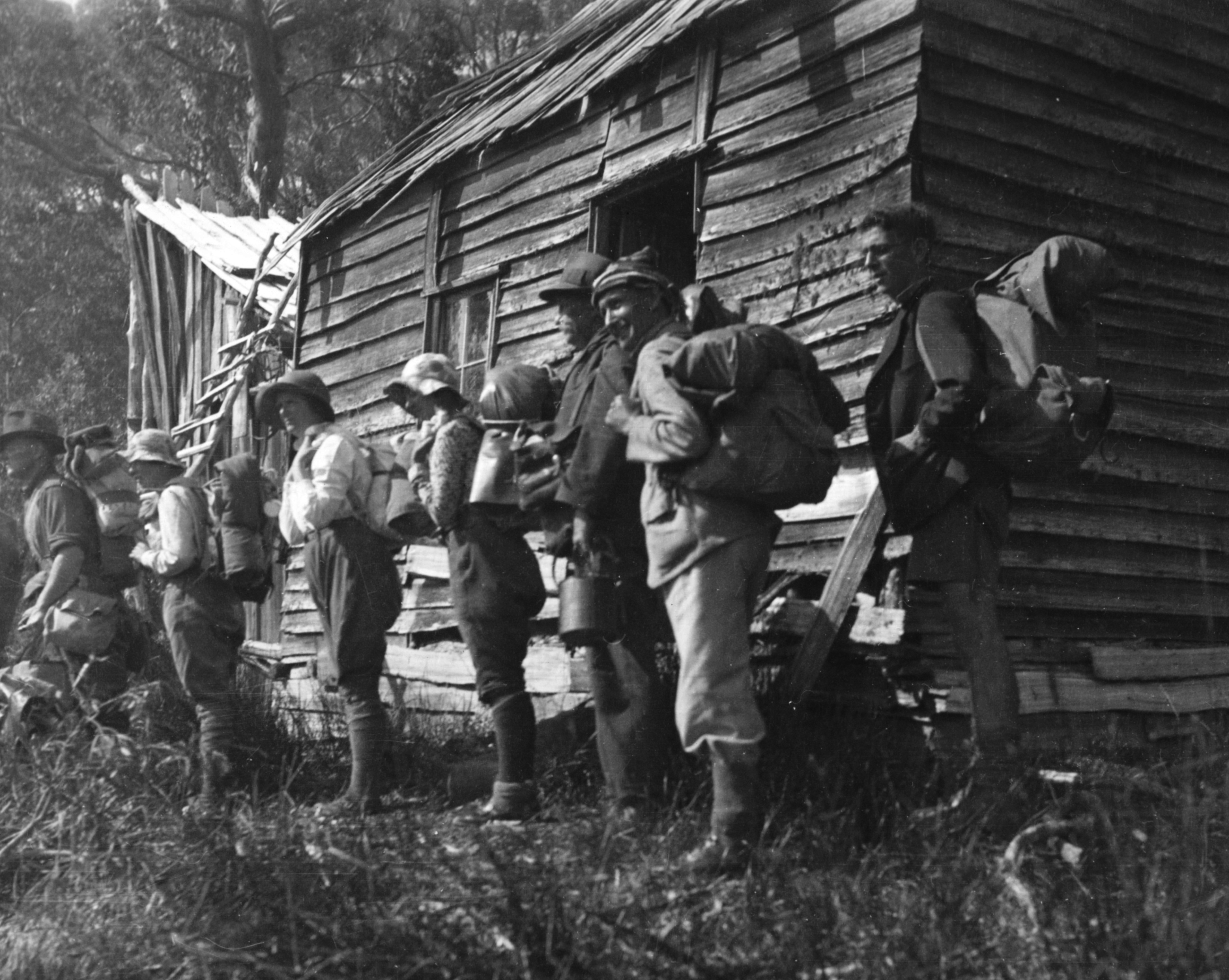

The Overland Track

The idea of threading a track through the two reserves to unite them seems to have started with Ron Smith, who in 1928 envisaged an ‘overland track’ connecting Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair, including a motor boat service on the lake.[11] Sections of track that could be linked already existed, including that marked by Weindorfer from Waldheim to Lake Will (the basis of the Horse Track), the Mole Creek Track between Pelion Plain and Pine Forest Moor, and hunters’ tracks from Pelion Plain through to Lake St Clair and the Cuvier Valley. Paddy Hartnett offered to cut the Overland Track for £440, but Bert Nichols did it for only £15.[12] He connected up sections of track and cleared others south of Pelion Plain to form the Overland Track in 1931.[13] Mining, hunting and tourism huts like Old Pelion, Lake Windermere and DuCane were adopted as staging posts along the track.

In 1934 Fergy established this dining room and associated huts at Cynthia Bay, Lake St Clair. Norton Harvey photo.

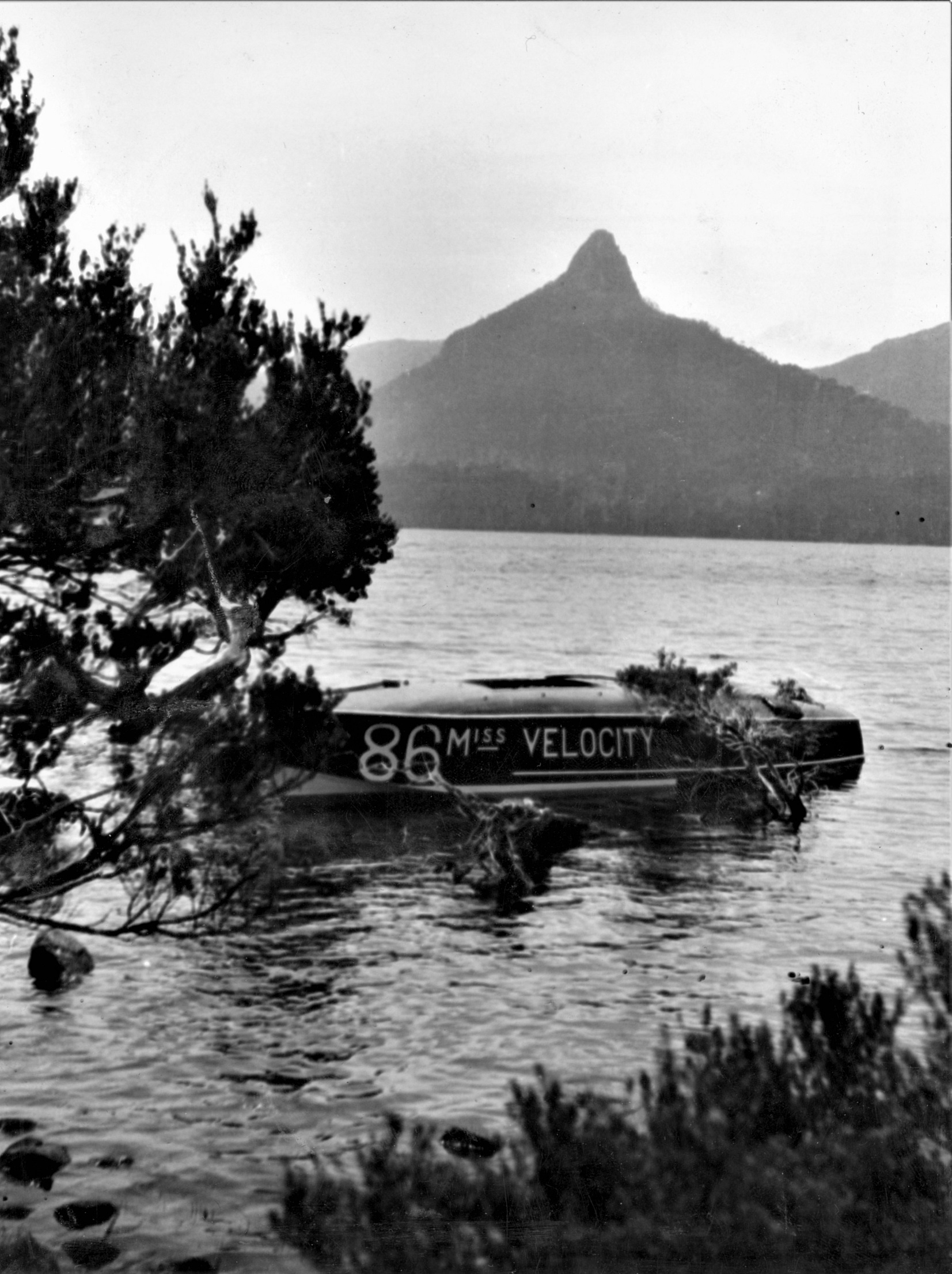

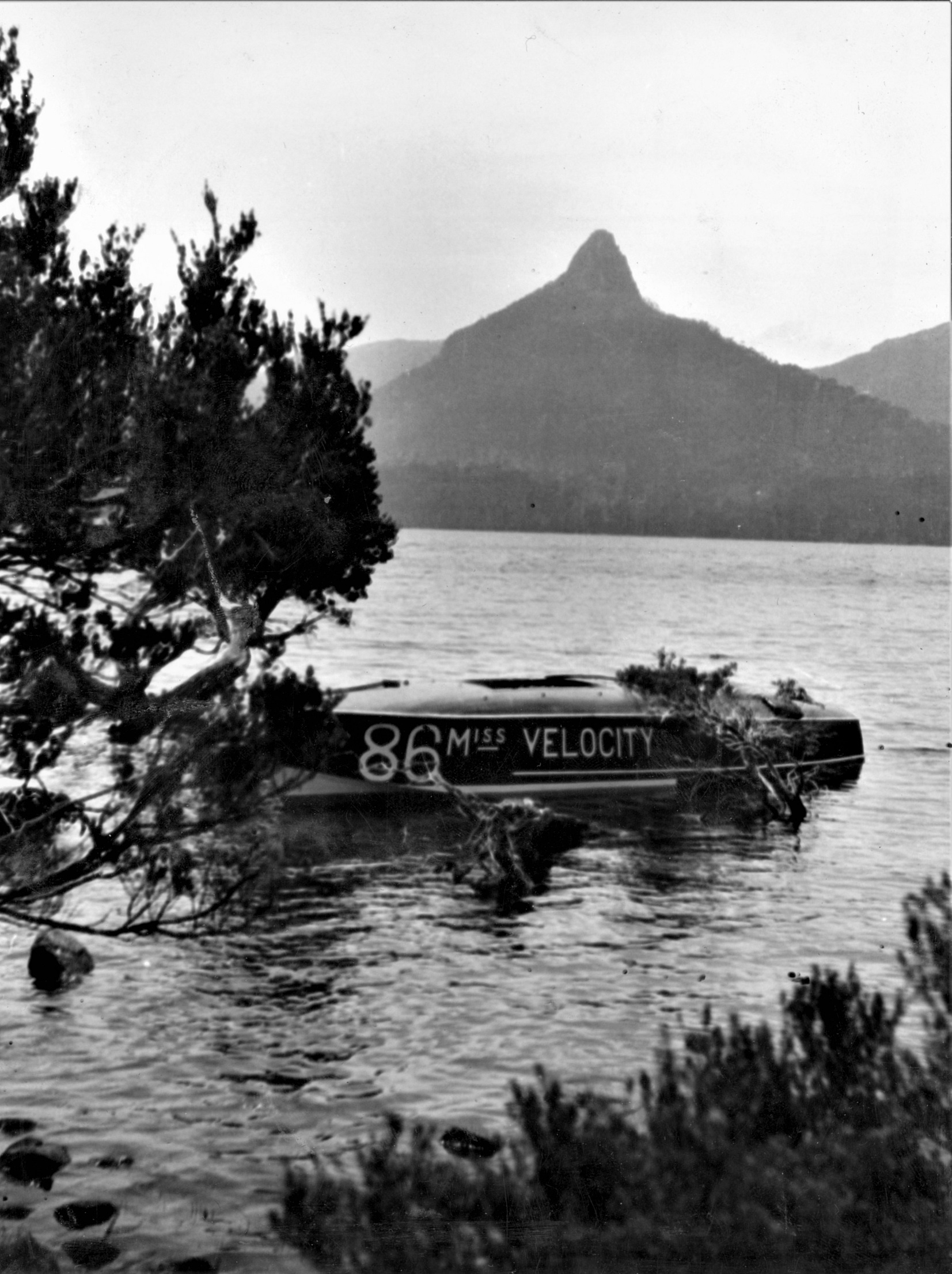

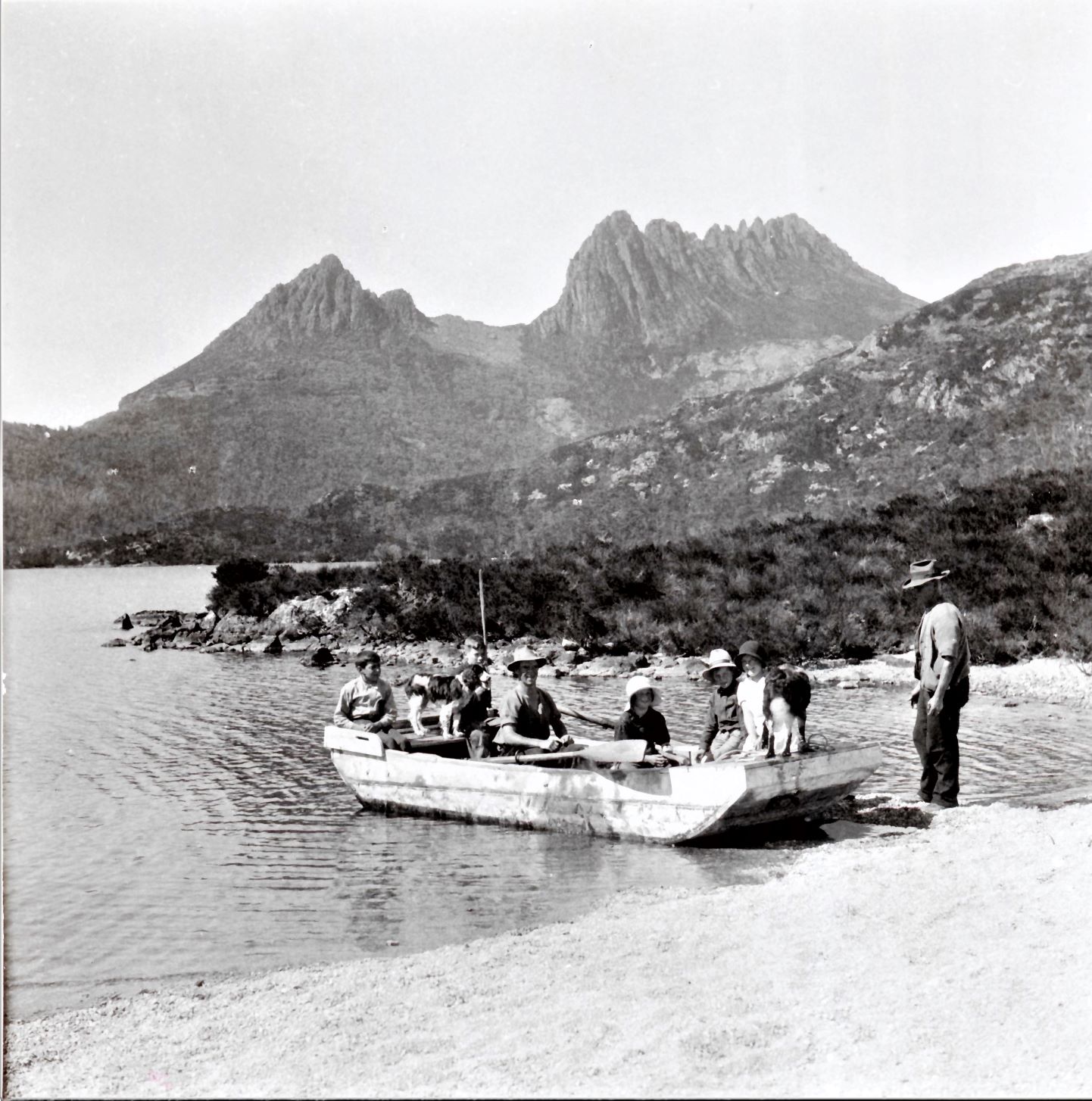

Although the official Overland Track went through the Cuvier Valley, it soon became standard procedure to cross Lake St Clair instead on tourist operator Albert ‘Fergy’ Fergusson’s motorboat. During the Great Depression Miss Velocity was an integral part of Bert Nichols’ guided tours on the Overland Track. Fergy’s tourist camp of sixteen tent-huts with earthen floors and a communal rustic dining room rivalled Weindorfer’s set-up at Cradle Valley.[14] He employed a housekeeper and owned a ‘frightful old bus’ with sawn-off cane kitchen chairs for seats, with which he drove walkers out to the Lyell Highway at Derwent Bridge.[15]

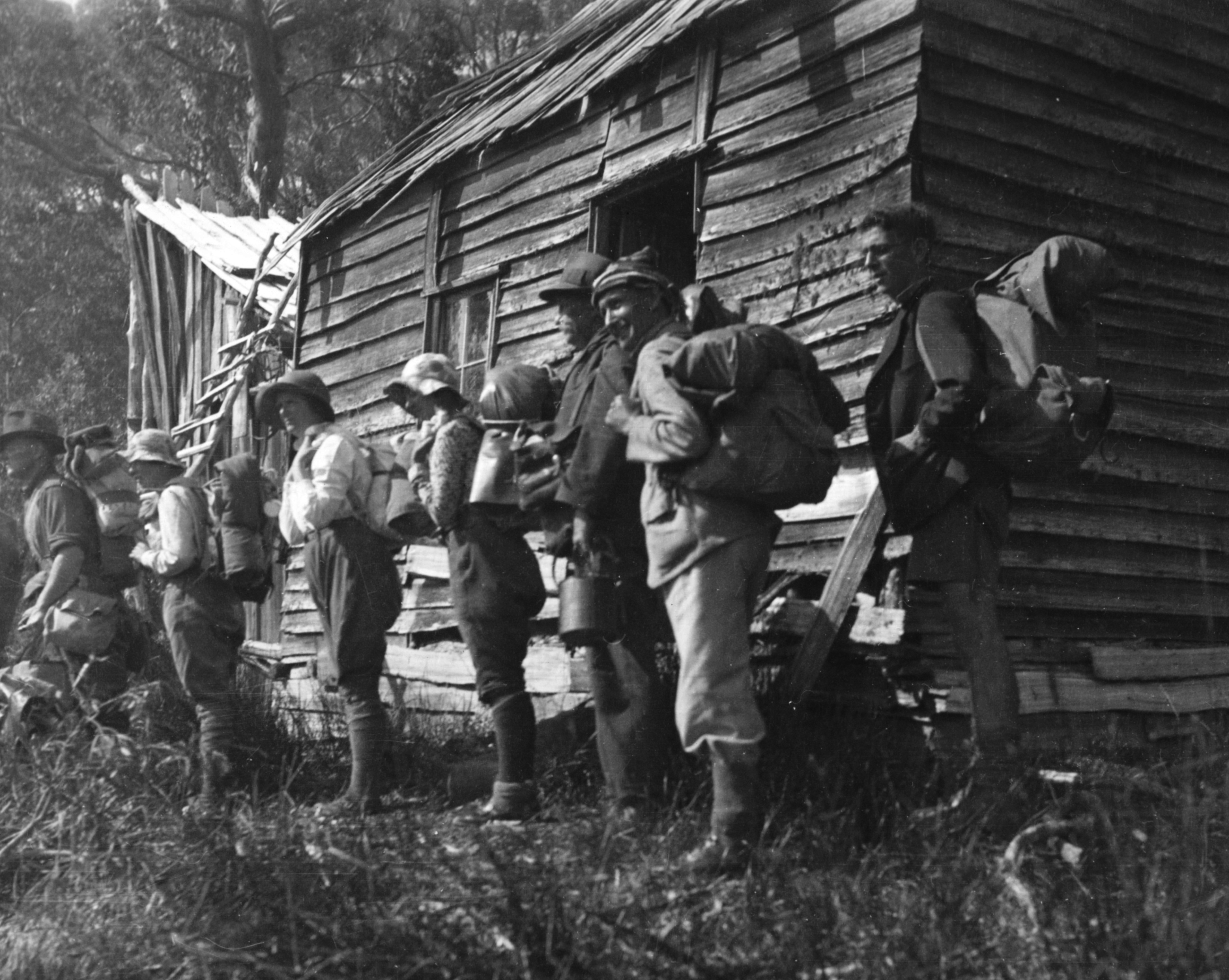

A 1929 Bert Nichols party at Windermere Hut. Marjorie Smith photo courtesy of the late Ian Smith.

Fergy’s racing boat Miss Velocity at rest in front of Mount Ida, Lake St Clair, 1929. Marjorie Smith photo courtesy of Ian Smith.

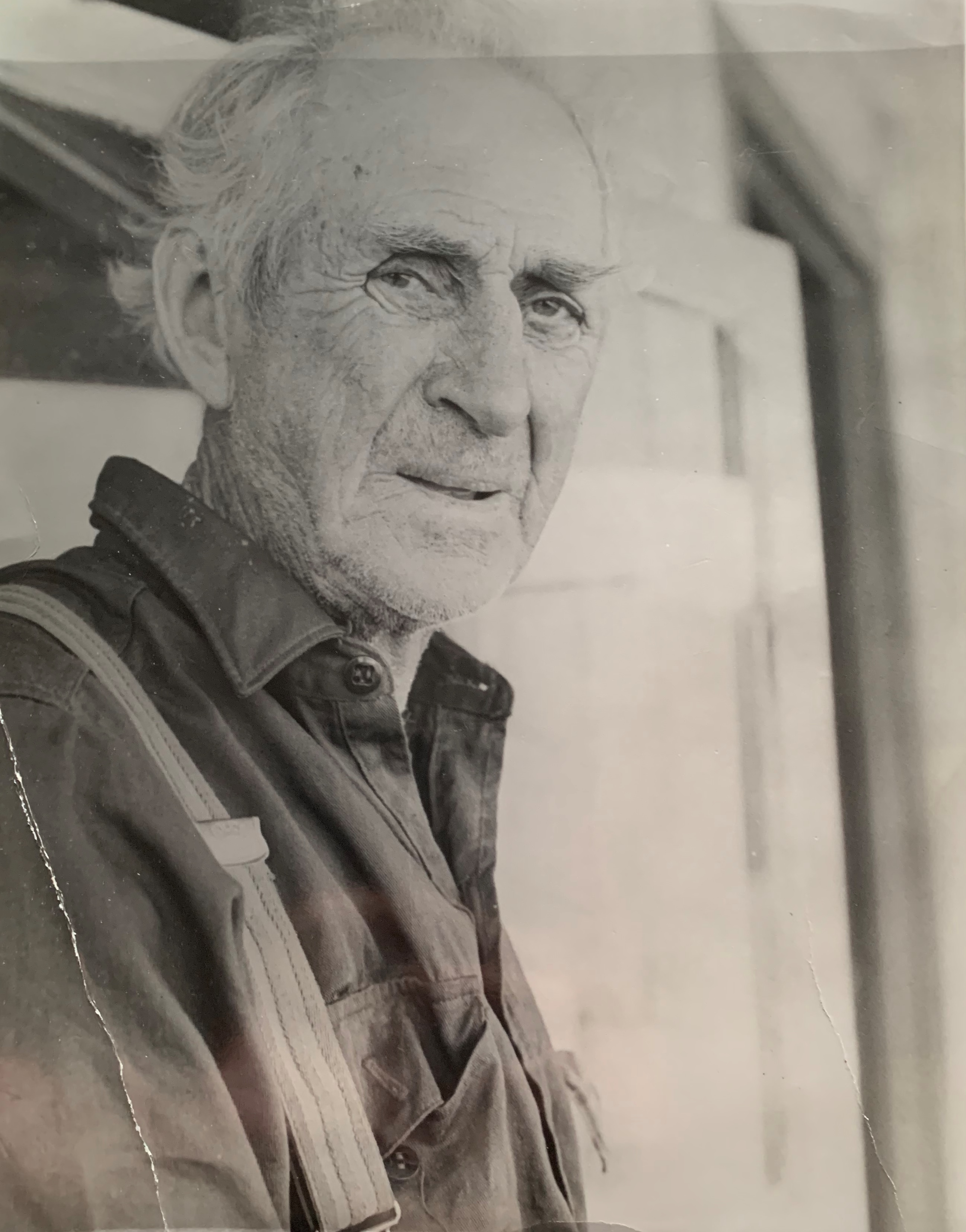

The death and wake of Gustav Weindorfer

Gustav Weindorfer died of cardiac arrest in Cradle Valley in May 1932, apparently in the act of trying to start his Indian motorcycle.[16] His name was already inscribed on his wife Kate’s headstone at Don in anticipation of him joining her there but a group of his friends arranged his interment in front of Waldheim.[17] Ironically, despite his love of the place, for years Weindorfer had been trying to sell and leave Waldheim.[18] Now he was stuck there!

The ceremony to unveil the memorial to Gustav Weindorfer at Waldheim, 1938, with Ron Smith in the foreground at right. Fred Smithies photo courtesy of Margaret Carrington.

The Austrian secular tradition of remembering departed loved ones was adopted at Weindorfer’s grave after his sister Rosa Moritsch sent a bunch of flowers and four small candles from his native land. These were placed on his grave on New Year’s Day 1933. For several decades Weindorfer’s good friend Ron Smith organised the annual New Year’s Day ceremony. The annual commemoration of Weindorfer’s life has assumed possibly unparalleled longevity among Australian public figures.

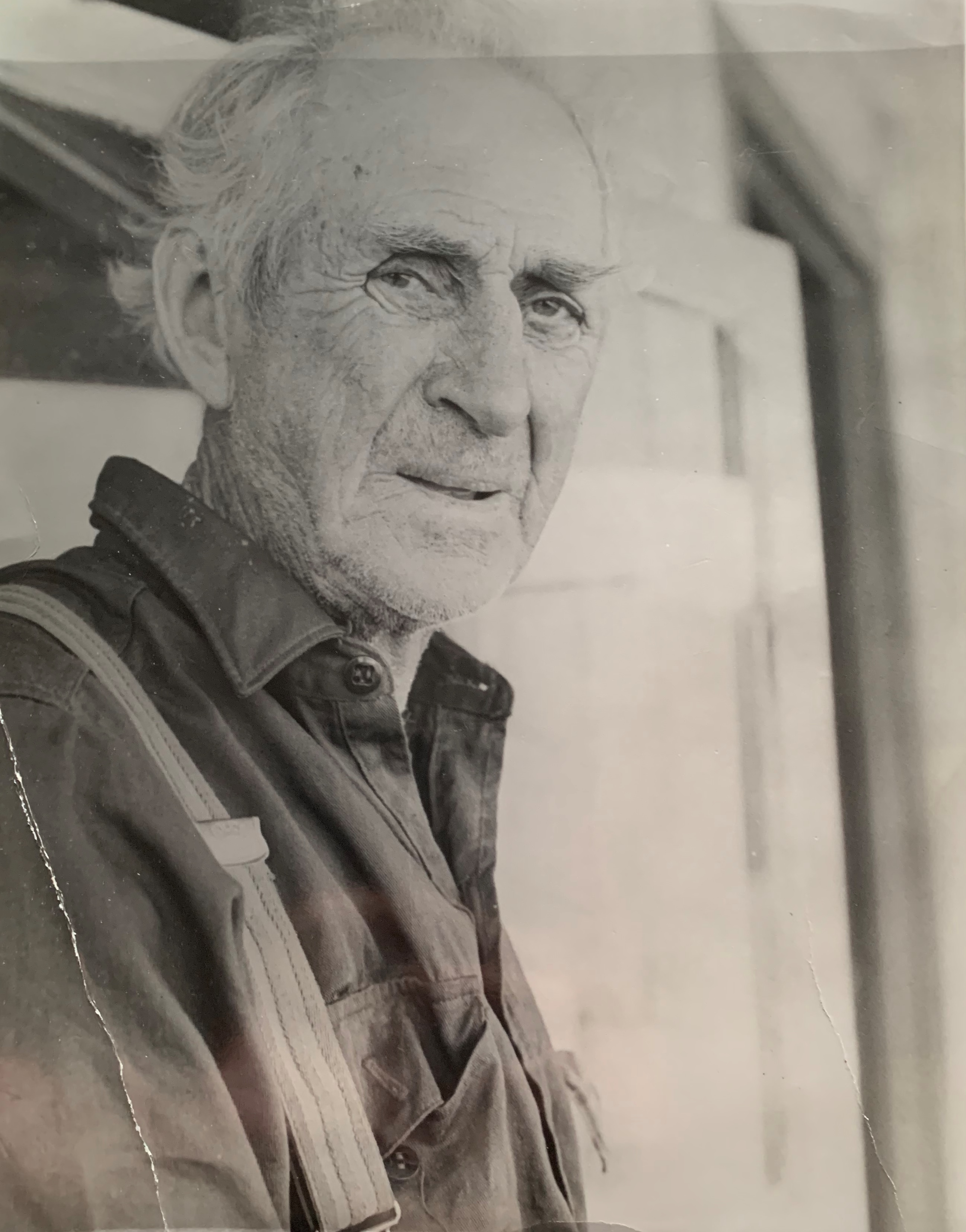

The work of the Connells

First Bert Nichols and then Barrington farmers Lionel and Maggie Connell looked after Waldheim before a syndicate of Weindorfer’s Launceston friends (George Perrin, Charlie Monds, Karl Stackhouse and Fred Smithies) bought the chalet from his estate.[19] They asked the Connells to stay on as managers. Lionel Connell had been snaring around Cradle Mountain for two decades and knew the country well. The Connells, with six sons and daughters to help them, set about making Waldheim financially viable by extending the building and improving access to it.

Lionel Connell loading up Weindorfer’s punt on Dove Lake, 1936. Ron Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

Os Connell digging out his family’s Sheffield–Cradle Mountain Passenger Service, 1943. Photo courtesy of Es Connell.

In the late 1930s the Connells had a tourism package for the Northern Reserve that far exceeded that of Gustav Weindorfer, ferrying visitors to and from Waldheim in their car, accommodating visitors, feeding them with produce from the farm at Barrington, guiding them around Cradle Mountain and even guiding them on pack-horse tours on the Overland Track.

Fergy’s other tub: early rangers

Ex-hunter and Overland Track guide Bert Nichols is said to have removed Overland Track markers when they were not needed in order to snare undetected in the fauna sanctuary. Nichols did other infrastructure work and was appointed ranger for two months in 1935. However, when the time came to appoint a permanent ranger the known poacher was not considered for the job.

A Lionel Connell hunting hut built with Dick Nichols still stood south of Lake Rodway as a reminder of the former’s past. Yet Connell was considered fit for a permanent posting as ranger.[20] The Connell family demonstrated great enterprise in their work at Cradle but conflict between Lionel’s roles of privately-employed tourism operator and government-employed ranger at the same location were soon obvious. To compound the issue, Connell managed Waldheim for Smithies and Karl Stackhouse. These men, as members of the CMRB, also effectively employed him as a ranger. CMRB Secretary Smith also had a family tie with the Connells.

Cyclists arriving at Old Pelion Hut, 1936. With them (left to right) are (possibly) Os Connell, Lionel Connell, Mount Field ranger HE Belcher and Director of the Government Tourist Bureau, ET Emmett. Photo courtesy of Es Connell.

Fergy overloading Miss Velocity’s more mundane replacement at Narcissus Landing, 1940. Ron Smith photo courtesy of Charles Smith.

The other remarkable early ranger was Fergy who, like Lionel Connell, combined the job with that of tourism operator. His toughest journey was not on the lake but in an upside-down bath. While building the original Pine Valley Hut, the Lake St Clair ranger lugged an iron tub to it about 10 km from Narcissus Landing by balancing it upside down on his shoulders and head, his forehead reputedly having been reinforced to mend a war wound (his World War One record suggests only that he suffered from shell shock and deafness). Stripping off in the heat, his curses echoing inside the bath, he was stark naked when he ran into a party of bushwalkers.

Extension of eastern and western reserve boundaries 1935 and 1939

The extension of fauna sanctuary boundaries to natural features was done with the intention of negating claims by hunters that they weren’t sure where the boundaries were. Tommy McCoy seems to have known. His Lake Ayr Hut was cheekily perched within sight of the reserve boundary. Reactions to it showed the distinction between the old-style conservationists in the park administration and the new ones of the bushwalking community. Cradle Mountain Reserve Board Secretary Ron Smith, a former possum shooter, respectfully left payment of threepence for a candle he removed from McCoy’s camp.[21] Hobart hikers, on the other hand, became conservation activists, puncturing McCoy’s canned food with a geological pick when they found his hut in 1948.[22] McCoy, like fellow snarers Paddy Hartnett, Bert Nichols and Lionel Connell before him, embraced the opportunities offered by tourism, building and repairing Overland Track huts. He was proprietor of Waldheim Chalet when he died in 1952.

Some of JW Beattie’s islands, southern end of Lake St Clair. Beattie photo, courtesy of Alma McKay.

Damming Lake St Clair 1937

The Art Deco Pump-house Hotel which juts into southern Lake St Clair, as if walking the plank for its crimes, is a symbol of gradually changing values. In 1922, in a joint lecture about ‘preserving’ the tract of land south from Cradle Mountain, Ray McClinton and Fred Smithies deplored the ‘firestick of the destroyer’ and the ‘ravages of the trapper’ but spruiked the hydro-electric potential of the region’s lakes.[23] Fifteen years later the naivety of this position became apparent when the Hydro-Electric Department dammed the Derwent River as part of the Tarraleah Power Scheme. After assuring the National Park Board that Lake St Clair would be unaffected, it raised the lake’s water level by more than a metre, sinking the golden moraine sand (the Frankland Beaches) and the accompanying islands once painted by Piguenit and photographed by Beattie.[24] A fringe of dead trees around the lake’s edge now greeted visitors. When photographers Stephen Spurling III and Frank Hurley joined the National Park Board in attacking the Hydro, Minister for Lands and Works Major TH Davies sprang to the institution’s defence, describing the damage as ‘unavoidable’.[25] This was a taste of what was to come at Cataract Gorge, Lake Pedder, the Pieman River and the Lower Gordon River.

Excision of the Wolfram Mine

With rearmament taking place in Europe in 1938, the raised price of tungsten (wolfram), used for strengthening steel, prompted an application to reopen the (Mount Oakleigh) Wolfram Mine, which was then included in the Cradle Mountain Reserve. CMRB Secretary Ron Smith penned the board’s opposition to the proposal, stating that no payable lode was likely to be found and that a successful application would set a bad precedent in terms of mining the reserve.[26] The subsidiary board’s concerns were not heeded. In a forerunner to national park and/or Wilderness World Heritage Area excisions at Mount Field, the Hartz Mountains and Exit Cave, the mine was temporarily excised from the scenic reserve as the Mount Oakleigh Conservation Area.[27] No Tasmanian reserved land ever seemed inalienable after this.

First load of logs from Mount Kate, 1943, with (left to right) George, Bernard and Leo Stubbs. Ron Smith photo, courtesy of Charles Smith.

The Mount Kate sawmill dispute and dissolution of the CMRB

The pitfalls of having vested interests on a government board again became apparent in December 1943 when Ron Smith took advantage of wartime stringency, rising timber prices and a finished access road to start harvesting King Billy pine on his property at Mount Kate. Over the next few years the definition of conflict of interest and the limits of official jurisdiction became increasingly blurred, as private land was resumed at Cradle Valley and the problematic CMRB was dissolved. Ironically, Smith and the Launceston syndicate had previously offered their land to the government but been refused. With Waldheim compulsorily acquired, Lionel Connell resigned as ranger. His sons Esrom and Wal were later reemployed in their own right as rangers at Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair. The appointment of the Cradle Mountain National Park Board in 1947 was the first step in placing the national park—as it was now known for the first time—on a sound footing, 25 years after the scenic reserves were initially gazetted. But the battle of ecology and economy continued.

[1] Gerard Castles, ‘Handcuffed volunteers: a history of the Scenery Preservation Board in Tasmania 1915–1971’, BA (Hons) thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 1986.

[2] This was the Scenery Preservation Act (1921). For an example of fears of loggers being locked out of the Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair Scenic Reserves, see E Alexander, ‘Cradle Mountain park: claims of timber area’, Advocate, 22 August 1921, p.5.

[3] ‘Fur farming: Cradle Mountain unsuitable: area further south chosen’, Mercury, 17 August 1925, p.6.

[4] ‘Lure of the skins’, Advocate, 22 August 1925, p.12.

[5] Statistics of Tasmania, 1922–23, p.58.

[6] Proclamation, Tasmanian Government Gazette, 8 March 1927, p.753.

[7] Proclamation, Tasmanian Government Gazette, 31 May 1927, pp.1412–13.

[8] Gerald Propsting to the secretary for Public Works, 4 August 1927, AA580/1/1 (TA); ‘Game Protection Act: illegal possession of skins’, Mercury, 17 August 1927, p.5.

[9] Fred Smithies, transcript of an interview by Margaret Bryant, 15 June 1977, NS573/3/3 (TA).

[10] Weekly Courier, 8 August 1928, p.1.

[11] Ron Smith to National Park Board Secretary Clive Lord, 27 August 1928, NS234/19/1/20 (TA).

[12] Paddy Hartnett to ET Emmett, 26 November 1928, PWD24/1/3; Director of Public Works to LM Shoobridge, Chairman of the National Parks Board, 13 March 1931, NS234/17/1/17 (TA).

[13] Bert Nichols to Ron Smith, 26 April 1931, NS573/1/1/4 (TA).

[14] Kevin Anderson, ‘Tasmania revisited: being the diary of Kevin Anderson, in which he related the incidents of his travelling to and through Tasmania with his companion, William Foo, from 12th April 1939 to the 26th April 1939’, unpublished manuscript (QVMAG), p.27.

[15] Jessie Luckman interviewed by Nic Haygarth.

[16] Bernard Stubbs interviewed by Nic Haygarth, c1993; Esrom Connell, in writing to Percy Mulligan, 20 September 1963 (NS234/19/122, TA), claimed to possess a diary in which Weindorfer recorded the failure of the motorbike to start. The present whereabouts of the diary are unknown. For the coronial inquiry into Weindorfer’s death, see AE313/1/1 (TA). The coroner determined the cause of death to be heart failure.

[17] ‘Papers relating to Coronial Enquiry into death of Gustav Weindorfer’, AE313/1/1 (TA).

[18] On 17 April 1928 Weindorfer wrote in his dairy, ‘This is very likely my last trip on the mountain’ (QVMAG). If he had a buyer for Waldheim then, the deal must have fallen through.

[19] Public Trustee to Fred Smithies, 11 November 1932, NS573/1/1/7 (TA).

[20] Minutes of the Cradle Mountain Reserve Board meeting, 26 April 1935, AF363/1/1, p.185 (TA).

[21] Ron Smith diary, 1940, NS234/16/1/41 (TA).

[22] Jessie Luckman interviewed by Nic Haygarth.

[23] ‘Cradle Mountain’, Advocate, 31 July 1922, p.2.

[24] ‘Level of water raised’, Mercury, 12 October 1938, p.13.

[25] National Park Board: ‘Level of water raised’, Mercury, 12 October 1938, p.13; Davies: ‘Lake St Clair: high level “unavoidable”’, Advocate, 13 October 1938, p.6; Hurley: ‘Tasmanians asleep’, Mercury, 30 January 1939, p.8; Spurling: S Spurling, ‘Scenic vandalism’, Examiner, 5 October 1940, p.3.

[26] Ron Smith to Minister for Mines, 3 May 1938, NS234/19/1/4 (TA).

[27] For an overview of the Wolfram Mine dispute, see Gerard Castles, ‘Handcuffed volunteers: a history of the Scenery Preservation Board in Tasmania 1915–1971’, pp.51–52.

by Nic Haygarth | 26/09/21 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

Stephen Spurling III (1876–1962) rode the rails and marched the mountains in his quest to snap Tasmania. Revelling in ‘bad’ weather and ‘mysterious’ light, this master photographer shot the island’s heights in Romantic splendour. His long exposures of the lower Gordon River are likely to have helped shape the reservation of its banks in 1908.[1] Snow-shoed, ear-flapped and roped to a tree, he captured Devils Gullet in winter and froze the waters of Parsons Falls. But Spurling wanted to record the full gamut of life. He was there when the whales beached, the bullock teams heaved, the apple packers boxed antipodean gold and floodwaters smashed the Duck Reach Power Station. His lens was ever ready.

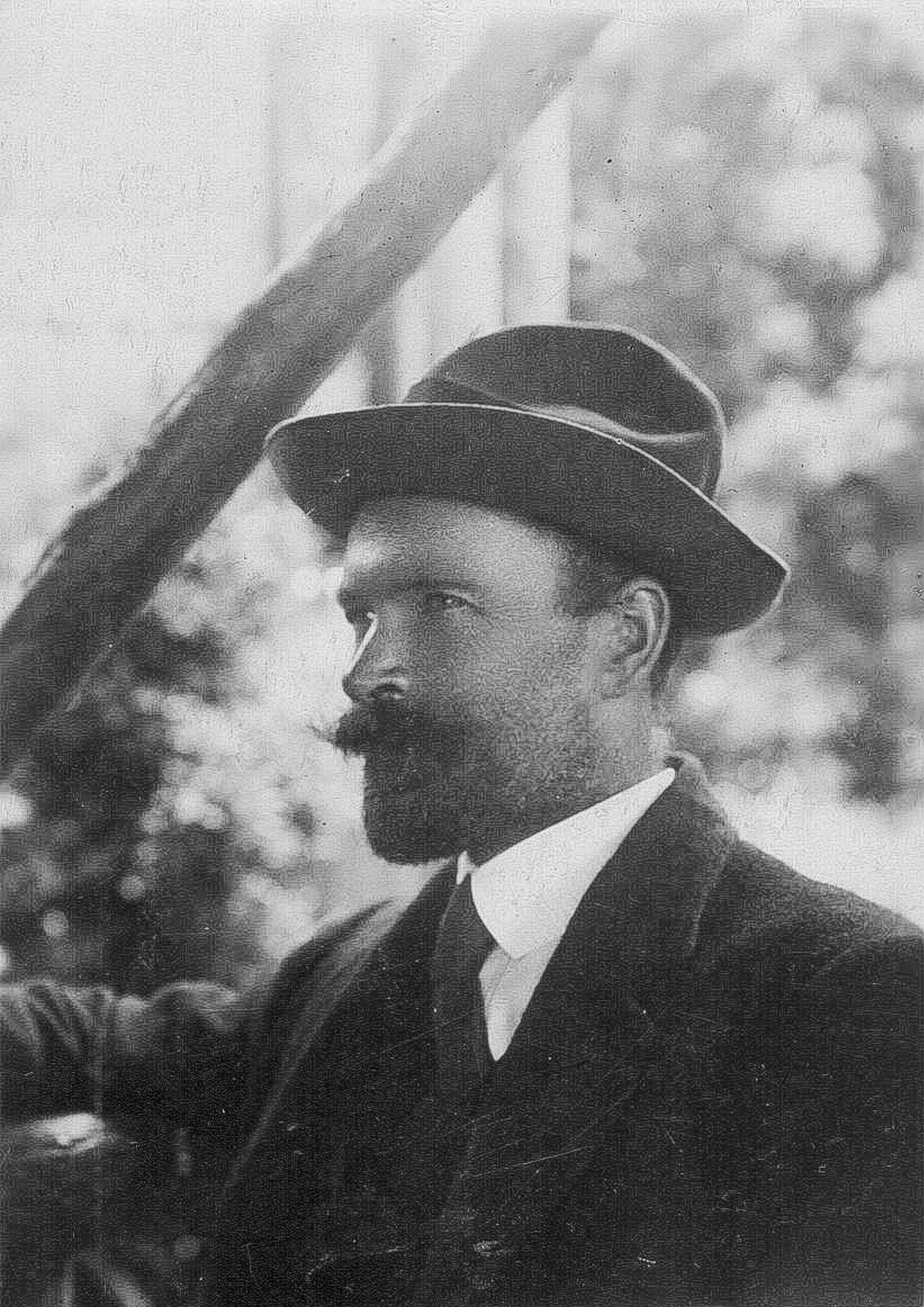

Stephen Spurling III in 1913, photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

Oddly, just about the only thing Spurling didn’t snap was a sack full of thylacine heads which he claimed to have seen at the Stanley Police Station in 1902. Forty-one years after the event, Spurling wrote that he watched ‘cattlemen from a station almost on the W coast [produce] two sacks of tigers’ heads (about 20 in number) and [receive] their reward’.[2] One-hundred-and-nineteen years after the event, this claim is hard to reconcile with the records of the government thylacine bounty. It adds a puzzle to the story of the so-called Woolnorth tigermen.

The Woolnorth tigermen

About 170 thylacines were killed at the Van Diemen’s Land (VDL Co) property of Woolnorth in the years 1871–1912, mostly by the company’s tigermen—a lurid title given to the Mount Cameron West stockmen. The tigermen had a standard job description for stockmen, receiving a low wage for looking after the stock, repairing fences, burning off the runs and helping to muster the sheep and cattle. They supplemented their income by hunting kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons, ringtail and brush possums. The only departure from the normal shepherd’s duty statement was keeping a line of snares across a neck of land at Green Point—now farming land at Marrawah—where the supposedly sheep-killing thylacines were thought to enter Woolnorth. The VDL Co paid their employees a bounty of 10 shillings for a dead thylacine, which was changed to match the government thylacine bounty of £1 for an adult and 10 shillings for a juvenile introduced in 1888. To make a government bounty application the tiger killer needed to present the skin at a police station, although sometimes thylacine heads sufficed for the whole skin.

It is not easy to work out how or even whether the Woolnorth tigermen generally collected the government thylacine bounty in addition to the VDL Co bounty. It is reasonable to think that the VDL Co would have encouraged its workers to do this, since doubling the payment doubled the incentive to kill the animal on Woolnorth. However, only two men are recorded as receiving a government thylacine bounty while acting as tigerman, Arthur Nicholls (6 adults, in 1889) and Ernest Warde (1 adult, 1 juvenile, in 1904).[3] This suggests that if Woolnorth tigermen and other staff received government thylacine bounties they did so through an intermediary who fronted up at the police station on their behalf.

Charles Tasman Ford and family, PH30/1/6928 (Tasmanian Archives Office).

Charles Tasman Ford and William Bennett Collins

The most likely candidates for the job of Woolnorth proxy during the government bounty period 1888–1909 were CT (Charles Tasman) Ford and WB (William Bennett) Collins. In the years 1891–99 Ford, a mixed farmer (sheep cattle, pigs, poultry, potatoes, corn, barley, oats) based at Norwood, Forest, near Stanley, claimed 25 bounties (23 adults and 2 juveniles), placing him in the government tiger killer top ten.[4] If you include bounty payments that appear to have been wrongly recorded as CJ Ford (5 adults, 1896) and CF Ford (1 adult, 1897), his tally climbs to an even more impressive 29 adults and 2 juveniles—lodging him ahead of well-known tiger tacklers Joseph Clifford of The Marshes, Ansons River (27 adults and 2 juveniles) and Robert Stevenson of Blessington (26 adults).[5] After Ford’s death in September 1899, Stanley storekeeper Collins claimed bounties for 40 adults and 4 juveniles 1900–06, his successful bounty applications neatly dovetailing with those of Ford.[6]

William Bennett Collins (standing at back) and family, courtesy of Judy Hick.

WB Collins’ Stanley store, AV Chester photo, Weekly Courier, 25 February 1905, p.20.

Where did their combined 75 tigers come from? The biggest source of dead thylacines in the far north-west at this time was Woolnorth. Twenty-six adult tigers were taken at Woolnorth in the years 1891–99, and 44 adults in the years 1900–06, making 70 in all. Tables 1 and 2 show rough correlations between Woolnorth killings and government bounty claims made by Ford and Collins. Ford, for example, received 7 payments 1892–93, the same figure for Woolnorth, while in the years 1894–97 his figure was 13 adults and theirs 16. Similarly (see Table 2), Collins claimed 16 adult and 4 juvenile bounties in 1900, a year in which 22 adult tigers were killed at Woolnorth; while in 1901 the comparative figures were 17 and 9. (Some of the data for Woolnorth is skewed by being recorded only in annual statements, which makes it look as though most tigers were killed in December. This was not the case: the December figures represent killings over the course of the whole year.) Clearly the Woolnorth tigers did not represent all the bounties claimed by Ford and Collins, but likely these made up the majority of their claims.

Table 1: CT Ford bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1891–99

| CT Ford |

29 – 2 |

Woolnorth |

26 – 0 |

| 31 July 1891 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 21 July 1892 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 9 Jany 1893 |

1 adult |

31 Dec 1892 |

2 adults |

| 27 April 1893 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 5 May 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 19 June 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 24 July 1893 |

1 adult |

18 Dec 1893 |

5 adults |

| 23 Jany 1894 |

2 adults |

20 Dec 1894 |

3 adults |

| 24 Feby 1896 |

5 adults |

30 Dec 1895 |

4 adults |

| 5 March 1897 |

1 adult |

7 Jany 1896 |

2 adults |

| 22 Sept 1897 |

3 adults |

19 Dec 1896 |

3 adults |

| 4 Nov 1897 |

2 adults |

Dec 1897 |

4 adults |

| 1 Feby 1898 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 2 August 1898 |

2 adults |

Dec 1898 |

3 adults |

| 30 May 1899 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

2 young |

|

|

Table 2: WB Collins bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1900–12

| WB Collins |

40 – 4 |

Woolnorth |

44 |

| 27 Feby 1900 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 16 Aug 1900 |

5 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1900 |

4 adults |

|

|

| 15 Nov 1900 |

4 adults, 4 young |

Dec 1900 |

22 adults |

| 13 Mar 1901 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 31 July 1901 |

7 adults |

|

|

| 28 Aug 1901 |

6 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1901 |

9 adults |

| 5 Nov 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1902 |

3 adults |

| 7 May 1903 |

2 adults |

Nov 1903 |

8 adults |

| 17 Nov 1903 |

4 adults |

1904 |

1 adult, 1 young (Warde) |

| 21 June 1906 |

1 adult |

1906 |

1 adult |

It would not have been difficult for Ford to act as a go-between for Woolnorth workers.[7] He had grazing land at Montagu and Marrawah/South Downs, east and south of Woolnorth respectively, and would have travelled via Woolnorth to reach the latter. He was also a supplier of cattle and other produce to Zeehan, a wheeler and dealer who bought up Circular Head produce to add to his consignments of livestock to the West Coast.[8] It would have been a simple thing for him on his way home from a Zeehan cattle drive to collect native animal skins and tiger skins/heads from the homestead at Woolnorth, presumably taking a commission for himself in his role as intermediary.

Of course that is not the only possible explanation for Ford’s bounty payments. His brothers Henry Flinders (Harry) Ford (three adults) and William Wilbraham Ford (6 adults) both claimed thylacine bounties. They had a cattle run at Sandy Cape, while William had another station at Whales Head (Temma) on the West Coast stock route.[9] It is possible that all the Ford government thylacine bounty payments represented tigers killed on their own grazing runs and/or in the course of West Coast cattle drives. CT Ford did, after all, take up land at Green Point, the place where the VDL Co killed most of its tigers in the nineteenth century. However, if the Fords killed a lot of tigers on their own properties or during cattle drives you would expect to see some evidence for it, such as in newspaper reports or letters. The Fords were, after all, not only VDL Co manager James Norton Smith’s in-laws, but variously his tenants, neighbours and fellow cattlemen. No evidence has been found in VDL Co correspondence. Oddly, when CT Ford shot himself at home in 1899, it was reported to police by his supposed employee George Wainwright—the same name as the Woolnorth tigerman of that time.[10] Perhaps this was the tigerman’s son George Wainwright junior, who would then have been about sixteen years old, and if so it shows that tigerman and presumed proxy bounty collector knew each other.

For all his 44 bounty claims, storekeeper WB Collins possibly never saw a living thylacine, let alone killed one. After Ford’s death, Collins appears to have established an on-going relationship with Woolnorth, being paid for three bounties in February 1900 before his store even opened for business. The VDL Co correspondence contains plenty of evidence that Collins dealt regularly with Woolnorth as a supplier and skins dealer.

The puzzle of Spurling’s sack of tiger heads

The only problem is Spurling. His claim about the 20 tiger heads being presented to the Stanley Police as a bounty claim doesn’t make a lot of sense. There is no record of such an event in the Stanley Police Station books, although, admittedly, tiger bounty payments rarely turn up in police station duty books or daily records of crime occurrences.[11] Still, 20 bounty claims presented at once would constitute a noteworthy event. The ‘almost W coast’ cattle station to which Spurling referred can only have been Woolnorth or a farm south of there, but his recollection seems wildly inaccurate..