by Nic Haygarth | 18/04/20 | Tasmanian high country history

When 52-year-old Maria Francis died of heart disease at Middlesex Station in 1883, Jack Francis lost not only his partner and mother to his child but his scribe.[1] For years his more literate half had been penning his letters. Delivering her corpse to Chudleigh for inquest and burial was probably a task beyond any grieving husband, and the job fell to Constable Billy Roden, who endured the gruesome homeward journey with the body tied to a pack horse.[2]

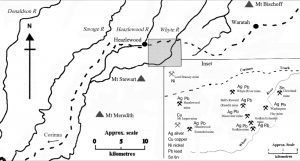

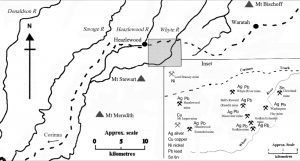

Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

By then Jack seems to have been considering retirement. He had bought two bush blocks totalling 80 acres west of Mole Creek, and through the early 1890s appears to have alternated between one of these properties and Middlesex, probably developing a farm in collaboration with son George Francis on the 49-acre block in limestone country at Circular Ponds.[3]

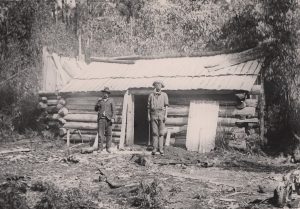

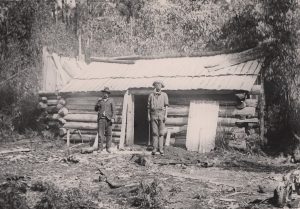

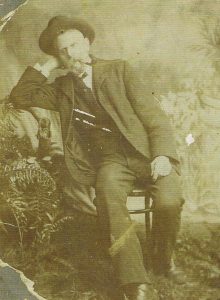

Jack Francis and second partner Mary Ann Francis (Sarah Wilcox), probably at their home at Circular Ponds (Mayberry) in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of Shirley Powley.

Here Jack took up with the twice-married Mary Ann (real name Sarah) Wilcox (1841–1915), who had eight adult children of her own.[4] Shockingly, as the passing photographer Frank Styant Browne discovered in 1899, Mary Ann’s riding style emulated that of her predecessor Maria Francis (see ‘Jack the Shepherd or Barometer Boy: Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis’). However, Mary Ann was decidedly cagey about her masculine riding gait, dismounting to deny Styant Browne the opportunity to commit it to posterity with one of his ‘vicious little hand cameras’.[5]

Perhaps Mary Ann didn’t fancy the high country lifestyle, because when Richard Field offered Jack the overseer’s job at Gads Hill in about 1901 he took the gig alone.[6] This encore performance from the highland stockman continued until he grew feeble within a few years of his death in 1912.[7]

Mary Ann seems to have been missing when the old man died. Son George Francis and Mary Ann’s married daughter Christina Holmes thanked the sympathisers—and Christina, not George or Mary Ann, received the Circular Ponds property in Jack’s will.[8] Perhaps Jack had already given George the proceeds of the other, 31-acre block at Mole Creek.[9]

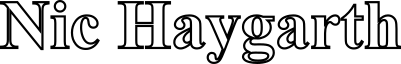

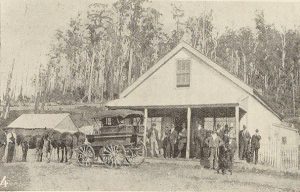

Field stockmen Dick Brown (left) and George Francis (right) renovating the hut at the Lea River (Black Bluff) Gold Mine for WM Black in 1905. Ronald Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

By the time Mary Ann Wilcox died in Launceston three years later, George Francis had long abandoned the farming life for the high country. He was at Middlesex in 1905 when he renovated a hut and took part in the search for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain.[10] Working out of Middlesex station, he combined stock-riding for JT Field with hunting and prospecting.

Like fellow hunters Paddy Hartnett and Frank Brown, Francis lost a small fortune when the declaration of World War One in July 1914 closed access to the European fur market, rendering his winter’s work officially worthless. At the time he had 4 cwt of ‘kangaroo and wallaby’ (Bennett’s wallaby and pademelon) and 60 ‘opossum’ (brush possum?). By the prices obtaining just before the closure they would have been worth hundreds of pounds.[11] Sheffield Police confiscated the season’s hauls from hunters, who could not legally possess unsold skins out of season.

The full list of skins confiscated by Sheffield Police on 1 August 1914 gives a snapshot of the hunting industry in the Kentish back country. Some famous names are missing from the list. Experienced high country snarer William Aylett junior was now Waratah-based and may have been snaring elsewhere.[12] Bert Nichols was splitting palings at Middlesex by 1914 but may not have yet started snaring there.[13] Paddy Hartnett concentrated his efforts in the Upper Mersey, probably never snaring the Middlesex/Cradle region. His double failure at the start of the war—losing his income from nearly a ton of skins, and being rejected for military service—drove him to drink.[14]

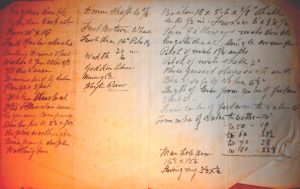

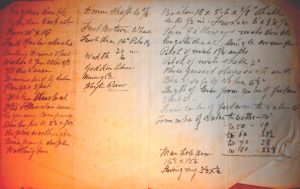

‘Return of skins on hand on the 1st day of August [1914] and in my possession’, Sheffield Police Station.

| Name |

Location |

Kangaroo/wallaby |

Wallaby |

Possum |

| George Francis |

Msex Station |

448 lbs |

|

60 skins |

| Frank Brown |

Msex Station |

562 skins+ 560 lbs |

|

108 skins |

| DW Thomas |

Lorinna |

960 lbs |

|

310 skins |

| William McCoy |

Claude Road |

600 lbs |

|

66 skins |

| Charles McCoy |

Claude Road |

40 lbs |

|

|

| Geo [sic] Weindorfer |

Cradle Valley |

31 skins |

|

4 skins |

| Percy Lucas |

Wilmot |

408 skins |

|

56 skins |

| G Coles |

Storekeeper, Wilmot |

|

5 skins |

|

| Jack Linnane |

Wilmot |

|

15 skins |

|

| WM Black |

Black Bluff |

50 skins |

|

3 skins |

| James Perry |

Lower Wilmot |

|

2 skins |

13 skins |

Most of those deprived of skins were bush farmers or farm labourers who hunted as a secondary (primary?) income, while George Coles was probably a middleman between hunter and skin buyer:

Frank Brown (1862–1923). Son of ex-convict Field stockman John Brown, he was one of four brothers who followed in their father’s footsteps (the others were Humphrey Brown c1855–1925, John Thomas [Jacky] Brown, 1857–c1910 and Richard [Dick] Brown). He appears to have been resident stockman at Field brothers’ Gads Hill Station in 1892.[15] Frank and Louisa Brown were resident at JT Field’s Middlesex Station c1905–17. He died when based at Richard Field’s Gads Hill run in 1923, aged 59, while inspecting or setting snares on Bald Hill.[16]

David William Thomas (c1886–1932) of Railton bought an 88-acre farm on the main road at Lorinna from Harry Forward in 1912.[17] His 1914 skins tally suggests that farming was not his main source of income—so the loss must have been devastating. Other Lorinna hunters like Harold Tuson were working in the Wallace River Gorge between the Du Cane Range and the Ossa range of the mountains.

William Ernest (Cloggy) McCoy (1879–1968), brother of Charles Arthur McCoy below, was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Sheffield.[18] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy and the uncle of the well-known snarer Tommy McCoy (1899–1952).[19]

Charles Arthur (Tibbly) McCoy (1870–1962) was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Barrington.[20] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy. Charles McCoy caught a tiger at Middlesex, depositing its skins at the Sheffield Police Office on 30 December 1901.[21] He was the uncle of the later well-known snarer Tommy McCoy.

Gustav Weindorfer (1874–1932), tourism operator at Waldheim, Cradle Valley, during the years 1912 to 1932. By his own accounts during 1914 he shot 30 ‘kangaroos’, eight wombats, six ringtails and one brush possum, as well as taking one ‘kangaroo’ in a necker snare.[22] While the closure of the skins market would have handicapped this struggling businessman, these skins would have been useful domestically, and the wombat and wallaby meat would have gone in the stew.

Percy Theodore Lucas (c1886–1965) was a Wilmot labourer in 1914, which probably means that he worked on a farm.[23] Nothing is known about his hunting activities.

TJ Clerke’s Wilmot store, Percy Lodge photo from the Weekly Courier, 22 April 1905, p.19.

George Coles (1855–1931) was the Wilmot storekeeper whose sons, including George James Coles (1885–1977), started the chain of Coles stores in Collingwood, Victoria.[24] George Coles bought TJ Clerke’s Wilmot store in 1912, operating it until after World War One. In 1921 the store was totally destroyed by fire, although a general store has continued to operate on the same site up to the present.[25] The five skins in George Coles’ possession had probably been traded by a hunter for stores. Coles probably sold them to a visiting skin buyer when the opportunity arose.[26]

John Augustus (Jack) Linnane (1873–1949) was born at Ulverstone but arrived in the Wilmot district in 1893 at the age of nineteen, becoming a farmer there.[27] Like George Francis, Linnane joined the search party for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain in 1905, suggesting that he knew the country well.[28] His abandoned hunting camp near the base of Mount Kate was still visible in 1908.[29] Enough remained to show that Linnane was one of the first to adopt the skin shed chimney for drying skins.[30] He also engaged in rabbit trapping.[31] In 1914 he was listed on the electoral roll as a Wilmot labourer, but exactly where he was hunting at that time is unknown.[32]

Kate Weindorfer, Ronald Smith and WM Black on top of Cradle Mountain, 4 January 1910. Gustav Weindorfer photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Walter Malcolm (WM) Black (1864–1923) was a gold miner and hunter at the Lea River/Black Bluff Gold Mine in the years 1905–15. The son of Victorian grazier Archibald Black, WM Black was a ‘remittance man’, that is, he was paid to stay away from his family under the terms an out-of-court payment of £7124 from his father’s will.[33] He joined the First Remounts (Australian Imperial Force) in October 1915 by falsifying his age in order to qualify.[34] See my earlier blog ‘The rain on the plain falls mainly outside the gauge, or how a black sheep brought meteorology to Middlesex’.[35]

James Perry (1871–1948), brother of a well-known Middlesex area hunter, Tom Perry (1869–1928), who was active in the high country by about 1905. Whether James Perry’s few skins were taken around Wilmot or further afield is unknown.

No tigers at Middlesex/Cradle Mountain?

George Francis survived the financial setback of 1914. Gustav Weindorfer in his diaries alluded to collaboration with him on prospecting and mining activities, but they hunted in different areas. In 1919 Francis co-authored the three-part paper ‘Wild life in Tasmania’ with Weindorfer, which documented their extensive knowledge of native animals, principally gained by hunting them. At the time, the authors claimed, they were the only permanent inhabitants of the Middlesex-Cradle Mountain area, boasting nine years (Weindorfer) and 50 years’ (Francis) residency. They also made the interesting claim that the ‘stupid’ wombat survived as well as it did in this area because it had no natural predators, since the thylacine did not then and probably never had frequented ‘the open bush land of these higher elevations’.[36] While this suggests that George Francis had never encountered a thylacine around Middlesex, it’s hard to believe that his father Jack Francis didn’t, especially given the story that Jack’s early foray into the Vale of Belvoir as a shepherd for William Kimberley was tiger-riddled.[37] It’s also a pity the authors didn’t consult the likes of Middlesex tiger slayers Charlie McCoy (see above) and James Mapps—or rig up a séance with the late George Augustus Robinson and James ‘Philosopher’ Smith.

The dog of GA Robinson, the so-called ‘conciliator’ of the Tasmanian Aborigines, killed a mother thylacine on the Middlesex Plains in 1830.[38] Decades later, ‘Philosopher’ Smith the mineral prospector came to regard Tiger Plain, on the northern edge of the Lea River, as the most tiger-infested place he visited during his expeditions. It was popular among the carnivores, he thought, because the Middlesex stockman’s dogs by driving game in that direction provided a ready food source. ‘I thought it necessary’, he wrote about his experience with tigers,

‘to be on my guard against them by keeping a fire as much as I could and having at hand a weapon with which to defend myself in the event of being attacked by one or more of them … ‘[39]

Smith killed a female tiger on Tiger Plain and took its four pups from her pouch but found they could not digest prospector food (presumably damper, potatoes, bully beef, wallaby or wombat).[40] Philosopher’s son Ron Smith had no reason to doubt his father, as he found a thylacine skull on his property at Cradle Valley in 1913 which is now lodged in Launceston’s Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery.[41] There were still tigers in the Middlesex region at the cusp of the twentieth century. Like ‘Tibbly’ McCoy, James Mapps claimed a government thylacine bounty at this time, probably while working as a tributor at the Glynn Gold Mine at the top of the Five Mile Rise near Middlesex.[42]

George Francis in his will described himself as a ‘shepherd of Middlesex Plains’, yet he met his maker in the Campbell Town Hospital. His parents were dead and he had no remaining relatives. The sole beneficiary of his will was Golconda farmer and road contractor William Thomas Knight (1862–1938), probably an old hunting mate.[43] Francis’s job at Middlesex was filled by the so-called ‘mystery man’ Dave Courtney (see my blog ‘Eskimos and polar bears: Dave Courtney comes in from the cold’), whose life, as it turns out, is an open book compared to that of his elusive predecessor.

[1] Died 11 October 1883, death record no.167/1883, registered at Deloraine, RGD35/1/52 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=maria&qu=francis#, accessed 15 February 2020; inquest dated 13 October 1883, SC195/1/63/8739 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC195-1-63-8739, accessed 15 February 2020. A pre-inquest newspaper reporter incorrectly attributed her death to suicide by strychnine poisoning (editorial, Launceston Examiner, 23 October 1883, p.1).

[2] It is likely that Jack Francis and Gads Hill stockman Harry Stanley conveyed Maria Francis’s body to Gads Hill Station, where Roden took delivery of it. See ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4; and ‘Supposed case of poisoning at Chudleigh’, Launceston Examiner, 13 October 1883, p.2. Later Roden had the job of removing Stanley’s body for an inquest at Chudleigh (Dan Griffin, ‘Deloraine’, Tasmanian Mail, 13 August 1898, p.26).

[3][3] For the land grant, see Deeds of land grants, Lot 5654RD1/1/069–71In 1890, 1892 and 1894 John and George Francis were both listed as farmers at Mole Creek (Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1890–91, p.200; 1892–93, p.288; 1894–95, p.260). Jack Francis was reported to have left Middlesex in March 1885, being replaced by Jacky Brown (James Rowe to James Norton Smith, 10 March 1885; and to RA Murray, 24 September 1885, VDL22/1/13 [TAHO]). However, he appears to have returned periodically.

[4] She was born to splitter John Wilcox and Rosetta Graves at Longford on 17 July 1841, birth record no.3183/1847 (sic), registered at Longford, RGD32/1/3 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=sarah&qu=wilcox, accessed 14 March 2020; died 25 October 1915 at Launceston (‘Deaths’, Examiner, 8 November 1915, p.1). Mary Ann’s youngest child, Eva Grace Lowe, was born in 1879.

[5] Frank Styant Browne, Voyages in a caravan: the illustrated logs of Frank Styant Browne (ed. Paul AC Richards, Barbara Valentine and Peter Richardson), Launceston Library, Brobok and Friends of the Library, 2002, p.84.

[6] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory for the period 1901–08 listed Jack Francis as an overseer at Gads Hill or Liena, while Mary, as she was described, was listed as a farmer at Liena, meaning Circular Ponds (1901, p.322; 1902, p.341; 1904, p.204; 1906, p.189; 1907, p.192; 1908, p.197).

[7] ‘A veteran drover’.

[8] ‘Return thanks’, Examiner, 2 March 1912, p.1; purchase grant, vol.36, folio 116, application no.3454 RP, 1 July 1912.

[9] Jack Francis bought purchase grant vol.18, folio 113, Lot 5654, on 25 November 1872. He divided it in half, selling the two lots on 6 May 1902 to Arthur Joseph How and Andrew Ambrose How for £30 each.

[10] ‘The mountain mystery: search for Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[11] 1 August 1914, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[12] See ‘William Aylett: career bushman’ in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.42–43.

[13] See ‘Bert Nichols: hunter and overland track pioneer’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.114.

[14] See ‘Paddy Hartnett: bushman and highland guide’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.93.

[15] On 20 April 1892 (p.179) Frank Brown reported stolen a horse which was kept at Gads Hill, Deloraine Police felony reports, POL126/1/2 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Well-known stockrider’s death’, Advocate, 4 June 1923, p.2.

[17] ‘Lorinna’, North West Post, 28 August 1912, p.2; ‘Obituary: Mr DW Thomas, Railton’, Advocate, 21 April 1932, p.2.

[18] Born 21 March 1879, birth record no.2069, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/57 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=william&qu=ernest&qu=mccoy. Accessed 10 April 2020.

[19] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[20] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[21] 30 December 1901, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] Gustav Weindorfer diaries, 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (TAHO).

[23] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.27.

[24] ‘About people’, Age, 22 December 1931, p.8.

[25] ‘Fire at Sheffield [sic]’, Mercury, 8 November 1921, p.5.

[26] Coles held a tanner’s licence in 1914 (‘Tanners’ licences’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 1 May 1914, p.109), but the legal requirement was that skins had to be sold to a registered skin buyer. Despite this, plenty of people tanned and sold their own skins privately.

[27] ‘”Back to Wilmot” celebration’, Advocate, 12 April 1948, p.2.

[28] 10 July 1905, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[29] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[30] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[31] On 18 April 1910, Linnane reported the theft of 200 rabbit skins from his hut valued at £2, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[32] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.26.

[33] ‘Supreme Court’, Age, 27 February 1885, p.6.

[34] World War One service record, https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1791278/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[35] Nic Haygarth website, http://nichaygarth.com/index.php/tag/walter-malcom-black/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[36] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Victorian Naturalist, vol.36, March 1920, p.158.

[37] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ’In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.2.

[38] George Augustus Robinson, Friendly mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834 (ed. Brian Plomley), Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 1966; 22 August 1830, p.159.

[39] James Smith to James Fenton, 14 November 1890, no.450, NS234/ 2/1/15 (TAHO).

[40] ‘JS (Forth)’ (James Smith), ‘Tasmanian tigers’, Launceston Examiner, 22 November 1862, p.2.

[41] Ron Smith to Kathie Carruthers, 26 September 1911, NS234/22/1/1 (TAHO); email from Tammy Gordon, QVMAG, 2019.

[42] Bounty no.242, 30 August 1898, LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO); ‘Court of Mines’, Launceston Examiner, 22 September 1897, p.3; 30 September 1897, p.3.

[43] Will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis, accessed 15 March 2020; ‘Funeral of Mr WF [sic] Knight’, Examiner, 15 April 1938, p.15.

by Nic Haygarth | 18/04/20 | Tasmanian high country history

When it comes to mythology, James ‘Philosopher’ Smith (1827–97), discoverer of the phenomenal tin deposits of Mount Bischoff in north-western Tasmania, has copped the lot. He was a mad hatter who ripped off the real discoverer, didn’t know tin when he saw it, threw away a fortune in shares (didn’t collect a single Mount Bischoff Co dividend) and ended up having to be saved from himself with a government pension.[1] Some of this hot air is still in circulation today—hopefully giving no one Legionnaire’s disease.

James ‘Philosopher’ Smith, wife Mary Jane and children Annie (left) and Leslie (right) at their near the Forth Bridge, 1877 or 1878. Peter Laurie Reid photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

Unbeknownst to Fields’ Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis, he has also been mired in Smythology. My favourite version of how Jack Francis rescued—or might have rescued, given the chance—Philosopher Smith during his Mount Bischoff expedition is this published poem by E Slater:

‘How Mount Bischoff was found’

Philosopher Smith was full of go,

He tried lots of times to get through the snow,

With his swag on his back he was not very slow,

And he crawled through the bush when his tucker was low.

So he had to turn back, to Jack Francis he came,

To the stockriders’ hut on Middlesex Plains,

I was in the hut when the old man came in,

And gave him some whisky, I think it saved him.

He told us quite plain that the tin it was there,

So he never gave in, or did not despair,

He got some more tucker and went out again,

This time he found Bischoff (it was teeming with rain).[2]

Not content with having Francis save a teetotaller with a bottle of whisky, this bold author decided to mooch in on the tall tale and make himself the saviour. The poem continues, inexplicably, to describe Smith’s triumphant return from Bischoff to the Middlesex Hut after finding the tin and his exit right via Gads Hill and Chudleigh.

Why would Smith take that circuitous route home? At the time, he owned the property Westwood at Forth, but he was also renting land at Penguin while he was involved in opening up the Penguin Silver Mine.[3] At least one author has claimed that Smith’s definitive prospecting expedition was mounted from Penguin up the Pine Road he had had cut in 1868 to enable piners to exploit the forests at Pencil Pine Creek near Cradle Mountain.[4]

However, in his notes Smith made it clear that he travelled from Forth via Castra, the logical route from Westwood to the gold-bearing streams of the Black Bluff Range and the mineralised country around the Middlesex Plains. His main plan was to test the headwaters of the Arthur River for a gold matrix, in support of which he had had a stash of supplies packed out to the base of the Black Bluff Range.

And so, according to Tasmania’s late-nineteenth-century Book of Genesis, James Smith unearthed hope and prosperity in the form of tin at Mount Bischoff on 4 December 1871. What Smith’s notes tell us is that, after a week of work at Mount Bischoff, he ran out of food and—with apologies to those who have claimed he ate his dog[5]—retreated to the hut of Field’s Surrey Hills stockman-hunter Charlie Drury to beg a feed. Drury, not Francis, was the stockman Smith recalled meeting during his Mount Bischoff expedition.[6]

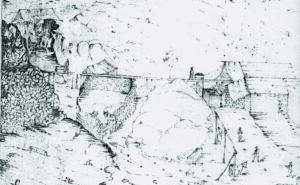

Action from the

Slaughteryard Gully Face of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mine, c1876, showing the yarding and slaughter of stock reflected in its name. Courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Regardless of Jack Francis’s non-glorification in the discovery of Bischoff, the tin mine brought a benefit to the denizens of Middlesex Station. The advent of the town of Mount Bischoff (Waratah), from about 1873, brought them closer to civilisation. However, there was no Mount Bischoff Tramway until 1877, and in its early days the town had no resident doctor. This meant that when a kick from a horse broke Jack Francis’s thigh at Middlesex in 1875, the nearest medical help was the unqualified ‘Dr’ Edward Brooke Evans (EBE) Walker of Westbank, Leven River (West Ulverstone). The round trip from the coast to Middlesex Station via the VDL Co Track—about 240 km—must have taken several days each way. ‘I had a nice jaunt to Middlesex’, Walker reported,

‘JT Field wrote asking me to go there to see a poor fellow a stock rider who had broken his thigh eight weeks before offering me £10!! to go there … I had to break it as it was 4 inches [9 cm] too short … I wrote and told him [JT Field] that he ought to supplement his offer but have had no answer … ‘[7]

Despite the pain, Jack—and/or his wife Maria Francis—made good use of this ‘down’ time, assembling a 30-shilling possum skin rug. ‘The rivers are not always fordable otherwise you would have the rugs more certain’, Jack told a customer, Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) local agent James Norton Smith.[8] He could ride, but for years the thigh injury still prevented him from walking far. In 1881 he asked the VDL Co to give him free passage to Waratah on the company’s horse-drawn tramway, enabling him to ride there after hitching his horse at the Surrey Hills stop.[9]

The establishment of Waratah also raised the Francis family’s social profile. One-time recipients of Her Majesty’s pleasure (they were both ex-convicts) became vice-regal hosts. In January 1878 Jack, Maria and possibly young George Francis put up Lieutenant Governor Frederick Weld at Middlesex Station. Escorted by a young Deloraine Superintendent of Police, Dan Griffin, and guided by Thomas Field, the vice-regal party negotiated Gads Hill on its way to visit the new mining capital—Weld being the first governor since George Arthur to tackle the VDL Co Track.[10] So it was that Jack Francis scored his moment of glory without even tempting the temperate Philosopher.

[1] For Smith finding the Mount Bischoff tin in the hut of stockman Charles Drury (‘Dicey’), see ‘The story of Bischoff’, Advocate, 24 April 1923, p.4. For Smith failing to identify the tin when he saw it, see, for example, Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Proceedings of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science (ed. A Morton), vol.iv, Hobart, 1892, p.342. For Smith squandering a fortune and having to be saved by the Tasmanian Parliament see, for example, ‘Parliamentary notes’, Launceston Examiner, 21 October 1878, p.2. For Smith ‘not making a cent’ out of Mount Bischoff tin and not collecting a single dividend from the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, see, for example, Carol Bacon, ‘Mount Bischoff’; in (ed. Alison Alexander), The companion to Tasmanian history, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 2005, p.243.

[2] E Slater, ‘How Mount Bischoff was found’, Waratah Whispers, no.15, March 1982; reprinted there from ‘an old newspaper cutting’.

[3] Application to register the Penguin Silver Mines Company was gazetted on 23 August 1870. The assessment roll for the district of Port Sorell for 1870 lists Smith as the occupant of a hut on 47 acres at Penguin owned by Thomas Giblin of Hobart (Hobart Town Gazette, 22 February 1870, p.298).

[4] See ‘Penguin old and new: record of great development’, Weekly Courier, 17 December 1927, p.35.

[5] See, for example, ‘Nomad’, ’Correspondence: Philosopher Smith’, Circular Head Chronicle, 25 May 1927, p.3.

[6] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/1/14/3 (TAHO).

[7] EBE Walker to James Smith, 8 July 1875, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[8] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 13 October 1875, VDL22/1/5 (TAHO).

[9] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 11 April 1881, VDL22/1/9 (TAHO).

[10] ‘Vice-regal’, Tribune, 28 January 1878, p.2; ‘DDG’ (Dan Griffin), ‘Vice-royalty at Mole Creek’, Examiner, 15 March 1918, p.6.

by Nic Haygarth | 03/04/20 | Story of the thylacine, Tasmanian high country history

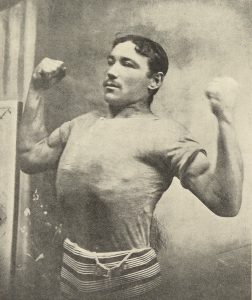

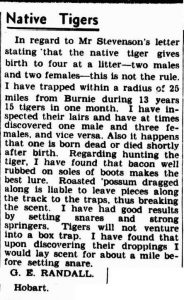

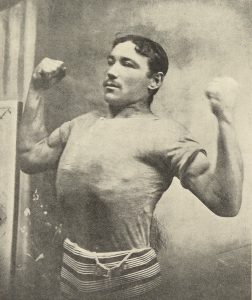

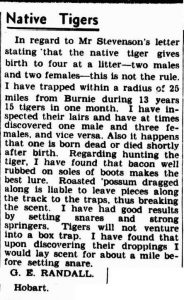

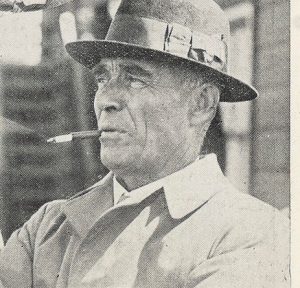

In 1945 one-time wrestler George Randall (1884–1963) recalled catching fifteen thylacines in the space of a month within 25 miles (40 km) of Burnie. He didn’t smother them in a bear hug. Randall reminisced that, upon finding tiger scats, he would lay a scent for half a mile from that point to his snares. The cologne no tiger could resist was actually the smell of bacon rubbed onto the soles of his boots.[1]

Champion wrestler George Randall, from the Weekly Courier, 18 February 1909, p.18.

George Randall in the Mercury, 12 December 1945, p.3.

Fifteen tigers—a big boast indeed. I was suspicious of those numbers. Who was Randall, and if he was such an ace tiger killer why had he never claimed a government thylacine bounty? Government bounties of £1 for an adult tiger and 10 shillings for a juvenile were paid in the years 1888 to 1909, after all, plenty of time in which he could leave his mark. The production of a carcass at a police station was the basis for a bounty application.

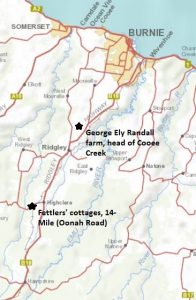

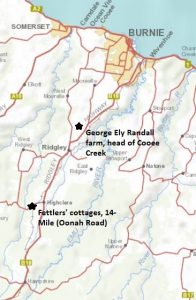

Randall was born at Burnie to George Ely Randall (1857–1907) and Emily Randall, née Charles (1871–1938).[2] By 1891 his father George Randall senior was a ganger maintaining the Emu Bay Railway (EBR) at Ridgley, south of Burnie. There were some tigers about, and it didn’t take much effort to find some Randalls killing one. In May 1892 Tom Whitton, who was aware of tigers coming about the gangers’ camp at night, set some snares and caught a large male. Two Randalls, George senior and his brother Charles, plus a fettler named Ted Powell, were at hand to help throttle the beast.

Wellington Times editor Harris added: ‘The tiger’s head was inspected by a large number of persons up to yesterday, many of whom remarked that they had never seen larger from a native animal; but yesterday the head had to be thrown away as it was manifesting signs of decay.’[3]

Thrown away?! So much for the £1 bounty. Perhaps the killers were too bloated on public admission fees to care about the bounty payment.

Another Randall killing came only two months later, when Powell and Charles Randall’s dogs flushed a tiger out of the bush at the 23-Mile on the EBR. Again the body was hauled into Burnie as a trophy.[4] Was a £1 government reward paid?

The government bounty records for the period May–July 1892 show the difficulty of reconciling newspaper reports with official records. There is no evidence of a bounty application having been made for the tiger killed on the EBR on 13 May 1892, but the one destroyed there in the week preceding 12 July 1892 is problematical. Was James Powell, who submitted a bounty application on 8 July, a relation of Ted Powell, the fettler involved in the two killings on the EBR? I could find no record of a James Powell working or residing in the Burnie area at that time, whereas two James Powells in pretty likely tiger-killing professions—manager of a highland grazing run, and bush farmer under the Great Western Tiers—were easily identified through digitised newspaper and genealogical records (see Table 1):

Table 1: Government thylacine bounty payments, May–July 1892, from Register of general accounts passed to the Treasury for payment, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

| Name |

Identification |

Application date |

Number |

| G Atkinson |

Probably farmer George Elisha Atkinson of Rosevears, West Tamar |

13 June 1892 |

2 adults[5] |

| A Berry |

Probably shepherd Alfred James Berry, Great Lake, Central Plateau |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[6] |

| John Cahill |

Farmer/prospector, Stonehurst, Buckland, east coast |

8 July 1892 |

1 adult[7] |

| WF Calvert |

Wool-grower/orchardist William Frederick Crace Calvert, Gala, Cranbrook, east coast |

21 July 1892 |

4 adults[8] |

| J Clifford |

Probably bush farmer/hunter Joseph Clifford of Ansons Marsh, north-east |

12 May 1892 |

1 adult[9] |

| Harry Davis |

Mine manager, Ben Lomond, eastern interior |

31 May 1892 |

2 adults & 1 juvenile[10] |

| CT Ford |

Mixed farmer Charles Tasman Ford, Stanley, north-west coast |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[11] |

| Thomas Freeman |

Shepherd at Benham, Avoca, northern Midlands |

12 May 1892 |

1 adult[12] |

| E Hawkins |

Shepherd William Edward Hawkins, Cranbrook, east coast |

9 July 1892 |

1 adult[13] |

| E Hawkins |

Shepherd William Edward Hawkins, Cranbrook, east coast |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[14] |

| Thomas Kaye |

Labourer at Deddington, northern Midlands |

31 May 1892 |

1 adult[15] |

| John Marsh |

John Richard James Marsh of Dee Bridge, Derwent Valley |

27 June 1892 |

1 adult & 1 juvenile[16] |

| W Moore junior |

Bush farmer William Moore junior, Sprent, north-western interior |

13 June 1892 |

1 adult[17] |

| E Parker |

Probably grazier Erskine James Rainy Parker of Parknook south of Cressy, northern Midlands |

27 June 1892 |

2 adults[18] |

| James Powell |

Probably manager, Nags Head Estate, Lake Sorell, Central Plateau, or bush farmer, Blackwood Creek, northern Midlands |

8 July 1892 |

1 adult[19] |

| Charles Pyke |

Mail contractor, Spring Vale, Cranbrook, east coast |

27 June 1892 |

1 adult[20] |

| A Stannard |

Probably shepherd Alfred Thomas David Stannard, native of Mint Moor, Dee, Derwent Valley but thought to have been in the northern Midlands at this time |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[21] |

| D Temple |

Shepherd David Temple senior, Rocky Marsh, Ouse, Derwent Valley |

21 July 1892 |

1 adult[22] |

| R Thornbury |

Farmer Roger Ernest Thornbury, Bicheno, east coast |

12 May 1892 |

1 adult[23] |

| H Towns |

Farmer Henry Towns, Auburn, near Oatlands, southern Midlands |

20 June 1892 |

1 adult[24] |

The two EBR slayings are not the only known tiger killings missing from the bounty payment record: two young men reportedly snared a live tiger near Waratah at the beginning of May 1892, but the detained animal accidentally hanged itself on its chain in a blacksmith’s shop; while on 22 July 1892 well-known prospector/sometime postman and seaman Axel Tengdahl shot a tiger that broke a springer snare on the Mount Housetop tinfield.[25] (Another July 1892 killing by ‘Bill the Sailor’ Casey at Boomers Bottom, Connorville, Great Western Tiers, was not rewarded until 5 August 1892, a lag of almost a month.[26]) The reasons for the Waratah and Housetop killings going unrewarded are not clear. While Tengdahl was in an inconvenient place to submit a tiger carcass to a police station, he was probably also snaring for cash as well as meat, so would have needed to leave the bush anyway in order to sell his skins to a registered buyer.

Anyway, back to Randall the tiger tamer. We know that young George Randall junior, eight years old in 1892, grew up with his elders hunting and chasing tigers. Then he went out on his own. He claimed that he trapped within a 40-km radius of Burnie for thirteen years, and that sometime during that period, in the space of a month, he killed fifteen tigers. It should be easy enough to figure out when this was. The ten-year-old would have been still living along the EBR with his family and presumably at school in 1894 when his mother was judged to be of unsound mind and committed to the New Norfolk Asylum.[27] In the years 1897–1901 (from the age of thirteen to seventeen) he was an apprentice blacksmith while living with his father at the 14-Mile (Oonah).[28] [29] He was still in the Burnie area in 1902 when he was cutting wood for James Smillie and driving a float for JW Smithies, but in 1903, as a nineteen-year-old, he was an insolvent fettler at Rouses Camp near Waratah.[30]

Emu Bay Railway south of Burnie, showing sites that George Randall may have hunted from. Base map courtesy of DPIPWE/

By 1907 Randall was a married man working at Dundas.[31] He did not return to the Burnie region after that, doing the rounds of Tasmania’s mining fields and rural districts for two decades with intermissions at Devonport, Hobart and Hokitika, the little mining port on the west coast of New Zealand’s South Island.[32] At Zeehan he was described as ‘the champion [wrestler] of Tasmania’, and he was noted not as a hunter but as a weightlifter and athlete.[33] More importantly, the blacksmith qualified as an engine driver and a winding engine driver, making him eminently employable in resource industries.[34] Randall finally settled at Hobart in 1929 at the age of 45.[35]

If we consider his Rouses Camp fettling a short aberration, the thirteen-year period in which Randall hunted around Burnie could have been approximately 1894 to 1906, that is, between the ages of ten and 22. The government bounty was available for the whole of this time, so why is there no record of George Randall’s prowess as a tiger tamer?

There are two possibilities. One is that Randall, a born showman, simply lied. The other possibility is that he killed or captured (he doesn’t say which) a lot of tigers but the evidence of same is hard to find.[36] There are few surviving records of the sale of live thylacines to zoos or animal dealers, or of bounty applications made through an intermediary like a hawker or shopkeeper. In some cases suspicion of acting as an intermediary even attaches to farmers—such as Charles Tasman (CT) Ford.

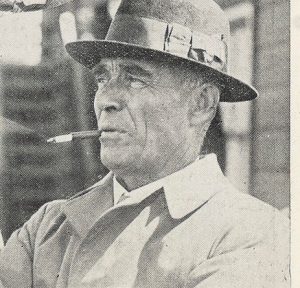

In later life Guildford’s Edward Brown assumed respectability as a breeder of race horses and hotelier. Stephen Spurling III photo from the Weekly Courier, 16 November 1922, p.28.

Randall may have been rewarded for fifteen thylacine carcasses through intermediaries such as shopkeepers, hawkers, skin buyers or some regular traveller to Burnie. Hunter/skin buyers such as Thomas Allen (15 adults and a juvenile, 1899–03)[40] and Edward Brown (7 adults, 1904–05)[41] operated in the Ridgley-Guildford area along the railway line, possibly accounting for some bounty payments for the likes of Randall, ‘Black Harry’ Williams, ‘Five-fingered Tom’ Jeffries and Bill Todd.

However, it does seem extraordinary that fifteen tiger captures or kills within the space of a month escaped public attention. We can assume that Randall never anticipated the scrutiny of his life that digitisation of records now allows us, let alone that someone who read his 1945 letter in the next century would try to dissect his life in order to verify his words. It is likely that Randall guessed that he had hunted in the Burnie region for thirteen years. Perhaps it was ten years, and perhaps his tigers took a lot longer to secure. Perhaps in a trunk in an attic somewhere is a mouldering trophy photo of the wrestler who wrangled tigers—dead or alive.

[1] GE Randall, ‘Native tigers’, Mercury, 12 December 1945, p.3.

[2] Born 1 July 1884, birth record no.1298/1884, registered at Emu Bay; died 14 July 1963, will no.44135, AD960/1/95, p.911 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall#, accessed 28 March 2020.

[3] ‘Capture of a native tiger’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 12 May 1892, p.2.

[4] ‘A big tiger’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 12 July 1892, p.2.

[5] Bounty no.147, 13 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[6] Bounty no.207, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[7] Bounty no.190, 8 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[8] Bounty no.203, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[9] Bounty no.118, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[10] Bounty no.136, 31 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[11] Bounty no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[12] Bounty no.119, 12 May 1892; LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[13] Bounty no.188, 9 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[14] Bounty no.210, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[15] Bounty no.135, 31 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[16] Bounty no.173, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[17] Bounty no.148, 13 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[18] Bounty no.172, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[19] Bounty no.189, 8 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[20] Bounty no.171, 27 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[21] Bounty no.206, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] Bounty no.208, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[23] Bounty no.117, 12 May 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[24] Bounty no.151, 20 June 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[25] ‘Waratah notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 10 May 1892, p.3; ‘Housetop notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 28 July 1892, p.2.

[26] ‘Longford notes’, Launceston Examiner, 14 July 1892, p.2; bounty no.236, 5 August 1892, LSD247/1/1 (TAHO).

[27] ‘Burnie: Police Court’, Daily Telegraph, 7 February 1894, p.1.

[28] ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 July 1901, p.3.

[29] ‘For sale’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 31 January 1902, p.3.

[30] ‘Arson: case at Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 20 March 1902, p.3; ‘New insolvent’, Examiner, 29 April 1903, p.4.

[31] He married Ethel May Jones on 22 May 1907 at North Hobart (‘Silver wedding’, Mercury, 23 May 1932, p.1). Dundas: ‘To-night at the Gaiety’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 7 September 1907, p.3.

[32] Zeehan: Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 31 August 1908, p.2; ‘Macquarie district’, Police Gazette Tasmania, vol.48, no.2595, 16 April 1909, p.81; Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Darwin, Subdivision of Zeehan, 1914, p.2. Devonport: Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Devonport, 1914, p.36. Waratah: ‘Waratah’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 17 October 1918, p.2; Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Darwin, Subdivision of Waratah, 1919, p.14. Hobart: Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Denison, Subdivision of Hobart East, 1922, p.30. Mathinna: ‘Personal’, Daily Telegraph, 30 September 1924, p.5. Cygnet: ‘Shooting at electric lines’, Mercury, 28 June 1926, p.4. Taranna: ‘Centralisation of school teaching’, Mercury, 12 May 1927, p.6. Hokitika: ‘Macquarie district’.

[33] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 31 August 1908, p.2; ‘Macquarie district’.

[34] Certificate of competency as second class engine drive, 1916, AA80/1/1, p.424, image 63 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall; Certificate of competency as mining engine driver, 1926, LID24/1/4, pp.109 and 109b (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=edward&qu=randall#, accessed 28 March 2020.

[35] ‘Motor cycle registrations’, Police Gazette Tasmania, vol.68, no.3629, 8 February 1929, p.33.

[36] Randall mentioned using springers, the supple saplings used to ‘spring’ the snare, generally employed in footer snares, which caught the animal by the paw, not being designed to kill it. Many thylacines sent to zoos were captured in footer snares.

[37] Bounties no.365, 31 July 1891 (2 adults); no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.402, 9 January 1893; no.71, 27 April 1893 (2 adults); no.91, 5 May 1893; no.125, 19 June 1893; no.183, 24 July 1893, no.4, 23 January 1894 (2 adults); no.239, 22 September 1897 (3 adults, ‘August 2’); no.276, 4 November 1897 (2 adults, ’27 October’); no.379, 1 February 1898 (‘4 December’); no.191, 2 August 1898 (2 adults, ‘7 July’); no.158, 30 May 1899 (’26 May’); no.253, 30 August 1899 (3 adults, ’24 August’); no.254, 30 August 1899 (2 juveniles, ‘24 August’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[38] Bounties no.43, 27 February 1900 (3 adults, ’22 February’); no.250, 16 August 1900 (5 adults, ’26 July’); no.316, 3 October 1900 (4 adults, ’27 September’); no.398, 15 November 1900 (4 adults and 4 juveniles, ’28 October’); no.79, 13 March 1901 (2 adults, ’28 February’); no.340, 31 July 1901 (7 adults, ’25 July’); no.393, 28 August 1901 (6 adults, ‘2/3 August’); no.448, 3 October 1901 (’26 September’); no.509, 5 November 1901 (’24 October 1901’); no.218, 7 May 1903 (2 adults, ’24 April’); no.724, 17 November 1903 (4 adults); no.581, 21 June 1906, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[39] Woolnorth farm journals, VDL277/1/1–33 (TAHO). The Woolnorth figure for 1900–06 excludes one adult and one juvenile killed by Ernest Warde and for which he claimed the government bounty payment himself (bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, LSD247/1/2 [TAHO]).

[40] Bounty no.374, 12 January 1899 (3 adults, ‘3 December’); no.401, 15 November 1900 (3 adults, ’15 June’); no.482, 21 January 1901 (3 adults, ’17 December’); no.22, 4 February 1901 (3 adults, ‘4 January’); no.985, 25 July 1902 (‘July’); no.1057, 27 August 1902 (’15 August’); no.1091, 17 September 1902 (‘4 September 1902’); no.462, 6 August 1903, (1 juvenile, ’24 July’), LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO). See ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 15 December 1900, p.2.

[41] Bounty no.233, 16 June 1904 (5 adults); no.125, 28 September 1905 (2 adults, ’31 August and 8 September’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 15/03/20 | Tasmanian high country history

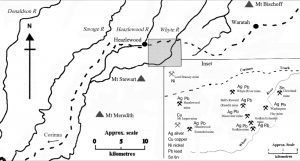

In 1891 the Godkin Silver Mining Company (GSM Co) spent about £7000 building a horse-drawn tramway to service its mine before the value of the property was even established. Its mine manager, Arthur Richard (AR) Browne, was more interested in installing machinery at the property 13 miles (21 km) south-west of Waratah. He wanted the Godkin to not only control the mining field’s transport but to be its custom smelter.[i] The GSM Co’s early half yearly reports are a litany of grand installation plans fed by Browne’s delusional ore values: £10,000 worth of ore were said to be on the claim in September 1890; £70,000-£80,000 worth in March 1891.[ii]

The mines on the 13-Mile silver field west of Waratah, Tasmania. The site of the village of Heazlewood on this map is the original site on the Heazlewood River. The village was later re-established further east. Base map drawn by the late Glyn Roberts.

However, the September 1891 report, tabled when Browne was on sick leave, painted a sobering picture of the mine. Only 27 tons of silver and lead ore from the southern section had been sold, for a profit of £218—not much of a return on the £7000 tramway.[iii] Directors were nervous.[iv] Notably, no banquet was called to celebrate completion of the second, 4-km-long stage of the Godkin Tramway to the Arthur River, which was tipped to occur in October 1891. No announcement of the achievement was ever made. Since the tramway never reached Waratah, it is safe to say that none of the construction costs were defrayed by hauling freight for other mining companies.

Remains of the headframe and flywheel at the South Godkin Shaft. Nic Haygarth photo.

Browne never returned to the Godkin, reportedly resigning in protest at directorial preference for tramway construction. His preference remained not proving the mine, but smelter building.[v] His last hurrah, delivered vicariously by Chairman of Directors TC Smart at the February 1892 half yearly meeting, was to compare the Godkin with Broken Hill mines and to continue to press for a smelter. Smart kept up the rhetoric, declaring in September 1892 that no Broken Hill mine had produced such rich ore at such a shallow level.[vi] When Browne returned to Tasmania in January 1893, it was as the Burnie agent for the Queensland Smelting Company, which envisaged buying ores from the new Tasmanian silver fields at the 13-Mile and Zeehan.[vii] Browne must have died an optimist in 1900 when, at the age of only 34, after stints at mines in Western Australia and British Columbia, he succumbed to asphyxia at the London home of his father, Lord Richard Browne.[viii]

The North Godkin Shaft today: pumps and windlass. Worthington pumps and a collapsed horse whim also help tell the story of the mine’s development and de-evolution. Nic Haygarth photo.

Despite securing another Broken Hill mining manager, Nathaniel Hawke, the GSM Co was already doomed.[ix] It had spent about £26,000 for a return of less than £300 when in 1892 government geologist Alexander Montgomery reported that it was no closer to success than when it started, having no payable ore on hand and needing to conduct deep sinking to prove its claim.

Montgomery also offered a cheaper alternative to deep sinking, but it was one which could never be definitive: driving a 1200-metre-long drainage tunnel from the Whyte River through both southern and northern leases to meet the engine shaft in the northern lease. While still working the upper, oxidised zone, this would test the entire property at a deeper level as well as drain it. The estimated cost of £2500–£3000 was well beyond the means of the GSM Co during tough economic times, and it succumbed to creditors in May 1894.[x] The surveyed township reserve of Stafford near the South Godkin site was never needed.

Paul Darby brown water rafting in Godkin Adit no.5. Nic Haygarth photo.

Gour pools in the Washington Mine Main Adit. A mixture of limestone and other minerals gives the 13-Mile mine workings rich calcite formations. Nic Haygarth.

The 13-Mile field today

The subsequent history of the 13-Mile mines is a typical one of de-evolution, both financial and technological. In the case of the Godkin, under-capitalised companies forced to revert to basic technology sought to exploit a lode that a heavily capitalised company had failed to even prove. The Victorian Magnet Company, which in 1912 completed the 1200-metre-long drainage tunnel, worked the North Godkin shaft using not a steam engine but a horse whim for motive power.[xi] By 1923 this company still used the Godkin Tramway to access the mine from the Corinna Road at Whyte River, but had converted it into a sledge track, the wooden rails having been torn up decades before in order to help build the nearby Whyte River Hotel.[xii] None of the 13-Mile mines was tested at depth until Electrolytic Zinc drilled the North Godkin site, Bell’s Reward, Discoverer and Godkin Extended in 1949—and the South Godkin Mine site remains undrilled to this day.[xiii] The likely presence of zinc in the Godkin’s pre-1917 finger dumps (that is, mullock that pre-dates the separation of zinc in Tasmania by the electrolytic process) and the possible presence of tin threaten to disturb what can now be seen as a fine historical mining interpretation site.

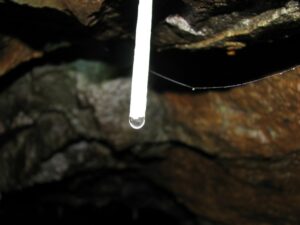

Hickmania troglodytes, Tasmanian cave spider with egg sac, Washington Hay Lower Adit. Nic Haygarth photo.

Well-rooted bottle, Godkin Mine. The tree root has grown around this discarded bottle over the course of nearly 130 years. Nic Haygarth photo.

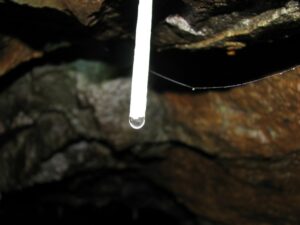

End of a calcite straw in one of the Godkin adits. Nic Haygarth photo.

Calcite shawl in one of the Godkin adits. Nic Haygarth photo.

Aside from pilfering by visitors, the 13-Mile field has remained largely undisturbed for almost a century. With so many artifacts still in place and with more than 50 adits, shafts and other workings, this is one Tasmania’s most impressive mining heritage sites. The expenditure demonstrated by the Godkin and Godkin Extended Tramways (1889–92), Cornish boiler (1891), blacksmith’s shop, ship’s tank, steam pumps, windlass, flywheel and head frame tell the tale of a fanatical response to the Broken Hill silver boom of 1888, while the horse whim at the North Godkin shaft recalls the technological reversal of later years. Similarly, the main tramway, with its in places corduroyed formation, bridge ruins, discarded iron wheels, axles, sledge artifacts and branch tramways to other mines, demonstrates not only the GSM Co’s efforts to capitalise on the mining field’s transport needs, but the de-evolution of the Godkin.[xiv]

[i] ‘Meeting of the company’, Mercury, 8 January 1891, p.3.

[ii] ‘Meeting: Godkin SM Co’, Mercury, 26 September 1890, p.3; ‘Godkin SM Co’, Mercury, 26 March 1891, p. 3.

[iii] The company would sell only seven more tons of ore, to Kennedy and Sons and the Clyde Works in Sydney, in 1892.

[iv] ‘Godkin Silver Mining Co’, Mercury, 29 September 1891, p.4.

[v] ‘The Godkin Mine’, Launceston Examiner, 5 November 1891, p.4.

[vi] ‘Meetings: Godkin SM Co’, Mercury, 1 October 1892, supplement, p.1.

[vii] GVS Dunn to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 31 May and 10 June 1892, VDL22/1/23; Arthur R Browne to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 24 January 1893, VDL 22/1/23 (TAHO).

[viii] ‘Queenstown notes’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 May 1900, p.4; ‘Sudden death of Lord Richard Browne’s son at Reigate’, Sussex Agricultural Express, 28 April 1900, p.10.

[ix] Little is known of Hawke’s performance, but his ability to defend himself with a gun prompted a conviction for assaulting the mine’s dismissed engineer in August 1892 (editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 August 1892, p.2).

[x] Alexander Montgomery, Report on the Godkin Silver Mine, Geological Surveyor’s Office, Launceston, 1892, p.3; advert, Launceston Examiner, 14 May 1894, p.2.

[xi] Secretary of Mines Annual report for 1912, 1913, p.37.

[xii] Nye, The silver-lead deposits of the Waratah district, p.118.

[xiii] DI Groves, The geology of the Heazlewood–Godkin area, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1966, pp.37–39; Allegiance Mining, EL 14/2001 Heazlewood Area, Tasmania: partial relinquishment report, 2002, p.20.

[xiv] See also Parry Kostoglou, An archaeological survey of the historic Godkin Silver Lead Mine, Archaeological Survey Report, 1999/03, Mineral Resources Tasmania, Hobart, 1999.

by Nic Haygarth | 15/03/20 | Tasmanian high country history

Tasmania has produced some disastrous mining ‘bubbles’. Stamper batteries and water wheels were rushed to the ‘Cornwall of the Antipodes’, the Mount Heemskirk tin field, in the early 1880s.[i] In the following decade the hydraulic gold craze crossed the Tasman Sea from Otago, while in 1910–12 the discovery of a so-called second Mount Lyell mine was celebrated in the Balfour copper boom. All of these were spectacular failures.

The ‘Broken Hill of Tasmania’ was another case of catastrophic piggybacking.[ii] It began in 1885 with prospector WR Bell returning to Tasmania from an exploratory tour of the Barrier Ranges silver field—later to become famous as the Broken Hill field—in western New South Wales. Bell put his Broken Hill experience to good use at home in the next five years, making a series of silver, galena and lead discoveries.[iii]

The mines on the 13-Mile silver field west of Waratah, Tasmania. The site of Heazlewood as marked on this map is the original site on the Heazlewood River. The village was later re-established on the 13-Mile field. Base map drawn by the late Glyn Roberts.

Among them was the Bell’s Reward mine on what became known as the 13-Mile silver lode, since it was 13 miles (about 21 km) west of Waratah, in Tasmania’s west coast mining province. However, it was the adjacent Godkin Mine that grabbed the headlines—and shareholders’ wallets—when in 1888 the Broken Hill silver boom reverberated across Tasmania. Never was there a better example of needless infrastructure spending before a mine was proven, or of the blinding effect of ‘mining fever’, than the Godkin.

Broken Hill invigorates the Tasmanian silver mines

In June 1887 Bell and his friend and business partner James ‘Philosopher’ Smith were granted 20-acre reward leases at what became known as the Bell’s Reward and Discoverer Mines respectively.[iv] Axes rang in the forest and cross-cut saws echoed in sawpits as a new mining village known as Heazlewood was established. Myrtle timber served for mining props, rails, building timber and firewood. Within a few years, five mine managers, two carpenters, a sawyer, a constable, a baker, a bank manager, three other storekeepers, a cricket team, hoteliers Joe and Emma Jupp and a branch of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association all called Heazlewood home.[v]

Insatiable prospector and innkeeper Josiah Jupp of the Heazlewood Hotel. Courtesy of Debra Talbot.

Mistress of the Heazlewood Hotel, Emma Jupp, equalling her husband in studio presentation. Courtesy of Debra Talbot.

Probable remains of the Heazlewood Hotel in 2016. Paul Darby photo.

Other prospectors arrived on the 13-Mile, including 23-year-old New Norfolk prospector Norman Godkin, representing the Dunrobin Prospecting Association.[vi] A touring phrenologist, Professor Klang, claimed to have divined Godkin’s suitability to a mining career from reading the bumps on his head, vocational advice which his customer adopted.[vii] Working south from the Bell’s Reward, Godkin found a gossan outcrop close to the northern side of a small tributary flowing into the Whyte River. The Godkin Mine was born.

Since Broken Hill was the model for development at the 13-Mile, the services of a Broken Hill manager were deemed essential. The Bell’s Reward syndicate rejected Lane, manager of the Block 14 Company mine at Broken Hill, after he demanded a salary of £2000 per year, plumping instead for Edgar L Rosman, former mine manager for the Broken Hill Proprietary itself.[viii] The pedigree of Arthur Richard (AR) Browne, the Godkin Silver Mining Company’s (GSM Co’s) Broken Hill man, was even more impressive. The English-born nephew of the Marquis of Sligo, he was educated at the Freiberg School of Mines, Saxony.[ix] Significantly, neither of these men had experience of Tasmanian geology, geography, climate, terrain or transport infrastructure.

In 1891, only months before a severe economic downturn, Bell and Smith floated the Bell’s Reward and Discoverer mines, pocketing £3000 each from their sale.[x] The shareholders of the Bell’s Reward Silver Mining Co, an under-capitalised, privately subscribed Melbourne company, grew dispirited in 1893 after two years of fruitless work when water burst into a crosscut, flooding the main shaft.[xi] By then the true meaning of the Bell’s Reward was apparent on the hill above Burnie, where Bell had used his share of the proceeds to raise Glen Osborne, still one of the city’s finest homes. This remains the second most impressive product of the 13-Mile field, albeit physically distant from the mines themselves.

Glen Osborne, WR Bell’s home on the hill at Burnie. Nic Haygarth photo.

Tramway to nowhere

The most impressive product of the 13-Mile field was the Godkin Tramway. Having raised much more money than any of the neighbouring mines, the GSM Co was able to exercise its delusions of grandeur. During winter the dray track between Waratah and the 13-Mile mines was a sea of mud. Possibly with Broken Hill’s Silverton Tramway in mind, the GSM Co took matters into its own hands. The well-known Huon timber tramway builder known as John Hay no. 2 (junior) was engaged to deliver the mine from isolation. He surveyed and built the 3-foot-6-inch gauge horse-drawn wooden-railed Godkin Tramway at a cost of about £7000, the wide gauge having been chosen to connect the line with the Van Diemen’s Land Company railway from Waratah to the port of Burnie.[xii] The Godwin Tramway Act (1891) empowered the company to charge neighbouring companies for freight on the line, potentially placing it in a position to dominate the mining field.

The Godkin Tramway formation today. Nic Haygarth photo.

Godkin Extended Tramway formation between the South and North Shafts of the Godkin Mine. Nic Haygarth photo.

Early bush tramways were constructed of whatever timber was available locally. Hay would have been familiar with the process of clearing and levelling the route, splitting myrtle sleepers, sawing and morticing the wooden rails and securing the line with gauge sticks. He set up a sawmill to cut the rails. The tramway rested on cross logs, on which were placed stringers, then four-inch slabs across those. The wooden rails were fixed on top of the slabs. Trestles were necessary in several places, but no ballast was used. Steel rails were placed on some of the curves on the line.[xiii]

The Godkin Tramway must have rivaled the famous Zigzag Railway in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales for switchback bends. At one point passengers could see two other sections of tramway and the Whyte River stretched out beneath them. The views were spectacular: ‘Here and there magnificent gullies and ravines, precipices of 200 ft or 300 ft on one side or the other that made one’s blood run cold to anticipate an overthrow’.[xiv] Yet it was said that the line enabled one horse to draw two tons of freight and/or passengers, with four trips possible in a day.[xv]

The mine remained unproven, but excitement mounted as some Godkin silver was smelted into a pendant for the governor, Sir Robert Hamilton.[xvi] Tramway builder Hay was a ‘strict total abstainer’, but soon he also became intoxicated—by silver. While constructing the tramway he struck his own silver lode near the Whyte River, floated a company, installed a concentrating plant alongside the tramway and set it up as the custom crusher for the district.[xvii]

In mid-February 1891 Minister of Lands and Works, Alfred Pillinger, opened the 4.8-km-long first stage of the Godkin Tramway to the bridge over the Whyte River.[xviii] Now the mine could be tested. The 200 tons of Godkin ore reported to be ready for export could be sent out.[xix] Pumping and winding machinery could be brought to the Godkin, enabling sinking to prove whether the mine lived down. Tenders were called for the supply and erection of 40-ton and 80-ton water jacket smelting furnaces at the mine and for the construction of a police station at ‘Godkin’s and Heazlewood’.[xx] The arrival of machinery in July 1891 also warranted a celebratory banquet in Waratah and, more ambitiously, a christening ceremony on site on the mine’s southern section.[xxi] Mine manager Browne guaranteed one of his invited guests ‘a regular little spree for the men & the visitors’.[xxii]

The bricked-in Austral Otis Godkin boiler, which has been on the field since 1891 and was once investigated as a possible thylacine lair. Nic Haygarth photo.

The boiler was officially inspected only once, in 1891. From AC705/1/1, 1885–1898 (TAHO).

Getting to the spree was a challenge. A party of guests, including Miss Seagrave, Browne’s future bride, left Waratah by coach and horseback for the start of the tramway. The coach broke down on the Magnet Range, forcing its passengers to wade through knee-deep mud for about a kilometre to the rails. At the mine, the Melbourne-based Austral Otis Elevator and Engineering Company boiler was inspected, after which Miss Inge and Miss Seagrave set the machinery in motion for the first time.[xxiii]

[i] The phrase ‘Cornwall of the Antipodes’ was credited to John Addis, manager of the Prince George Mine on the Mount Heemskirk tin field, in 1881 (‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 7 December 1881, p.3).

[ii] ‘A Bushman’, ‘The Whyte River Silver Field’, Mercury, 27 February 1890, p.3, described the field as being ‘in the opinion of many … destined to be the Broken Hill of Tasmania’.

[iii] For Bell, see Nic Haygarth, ‘Richness and prosperity: the life of WR Bell, Tasmanian mineral prospector’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.57, no.3, December 2010, pp.203–35.

[iv] PB Nye, The silver-lead deposits of the Waratah district, Geological Survey Bulletin no.33, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1923, p.109.

[v] For Smith being elected vice-president of the Heazlewood Cricket Club, see JE Lyle to James Smith, October 1888, no.485; and 15 October 1888, no.500; NS234/3/16 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Hobart [hereafter TAHO]).

[vi] ‘In Chambers’, Mercury, 7 November 1888, supplement p.1.

[vii] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 19 November 1890, p.2.

[viii] WR Bell to James Smith, 3 March and 4 March 1891, NS234/3/19 (TAHO).

[ix] ‘Mining news’, Daily Telegraph, 7 June 1889, p.3; ‘Queenstown notes’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 May 1900, p.4.

[x] Agreements dated 3 February 1891 and 15 June 1891, NS234/3/19 (TAHO).

[xi] J Harcourt Smith, ‘Report on the mineral district between Corinna and Waratah 28 July 1897’, Secretary of Mines Annual Report 1997, Parliamentary Paper 44/1897, pp. i–xix.

[xii] ‘Meetings: Godkin’s SM’, Mercury, 29 March 1890, supplement, p.1; Henry Penn Smith, Godkin Silver Mining Company, to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 23 February 1891, VDL22//21 (TAHO).

[xiii] Arthur R Browne to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 27 September and 4 October 1891, VDL22/1/21 (TAHO).

[xiv] ‘Whyte River silver field’, Launceston Examiner, 22 July 1891, supplement p.2.

[xv] ‘The Godkin Tramway: opening ceremony’, Wellington Times, 18 February 1891, p.3.

[xvi] ‘Personal’, Daily Telegraph, 1 October 1920, p.8.

[xvii] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 30 January 1891, p.3; ‘Obituary’, Examiner, 16 May 1902, p.7.

[xviii] ‘The Godkin Tramway: opening ceremony’.

[xix] ‘Waratah notes’, Wellington Times, 27 May 1891, p.3.

[xx] Adverts, Daily Telegraph, 10 June 1891, p.1 and 22 August 1891, p.7.

[xxi] ‘Starting the Godkin machinery’, Mercury, 20 July 1891, p.3.

[xxii] Arthur R Browne to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 12 July 1891, VDL22/1/21 (TAHO).

[xxiii] ‘Starting the Godkin machinery’. Details of the boiler inspection can be found in AC705/1/1, 1885–1898 (TAHO).