by Nic Haygarth | 09/03/24 | Circular Head history

Lasseter’s Reef wasn’t the first pot of gold to go missing.[1] Many goldfields have their holy grails, the tale of a fabled reef found but then lost, tantalising generations of prospectors. On Tasmania’s Arthur River it was the reputed reef at the Blue Peaked Hill,[2] but even ‘Australia’s biggest dairy farm’ Woolnorth, in the state’s north-western corner, wears a tale of gilded woe.

The unlikely claimant at Woolnorth was John Elmer (1801–80), who is said to have been born at Barnham, St Edmundsbury Borough, in Suffolk, England. He married Frances Kemp in that town in 1823.[3] On 22 March 1832, along with their four daughters and five other men, they arrived at Stanley on the barque Forth as indentured servants to the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co).[4]

The Woolnorth property showing its original eastern boundary. TOPOGRAPHIC BASEMAP FROM THELIST copyright STATE OF TASMANIA

The settlement on the coast at Woolnorth Point was then only three years old, consisting of a store, six cottages, a stable, a blacksmith’s shop and a jetty where produce could be loaded and goods landed.[5] The place was isolated, conditions primitive and rations meagre. Indentured servants were required to stay long enough to work off their passage fares, but three Forth arrivals and two other indentured servants voted with their feet by absconding in October 1832.[6] The Elmers stayed, John’s employment even surviving an incident in October 1834 when he struck Woolnorth overseer Samuel Reeves during a pay dispute.[7] A splash of gold across the drudgery of tending Saxon ewes, draining marshland, milking cows and keeping house would have been welcome.[8] However, nobody entertained ideas of a gold bounty in the years before the Californian rushes of 1848–55. Few would have known gold if they fell over it.

Shepherd at Woolnorth and Cheshunt

The Elmer family endured a decade at remote Woolnorth before taking up a Launceston butchery.[9] That move landed John Elmer in the Insolvency Court, after which he appears to have joined the wool-grower, architect and botanist William Archer IV’s Cheshunt property south-west of Deloraine.[10] Elmer would have been an interesting witness on the subject of thylacine predation on sheep, having been a shepherd at a time when few attacks were reported at either Woolnorth or Cheshunt. In 1851, when Elmer was hired or rehired as a Cheshunt shepherd and overseer at an annual salary of £40, he and Frances already had a family of six young children.[11]

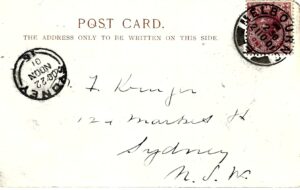

James (Edward James) Elmer and his wife Louisa Annie Diprose. Courtesy of Bruce Hull.

James Elmer

One of their offspring was Edward James Elmer (c1835–1916), who called himself James Elmer.[12] He claimed to be ‘the oldest white born under the VDL Company’. Many seventeen-year-olds must have raced off to the goldfields at Forest Creek, Loddon River or Creswick with their fathers circa 1852 when the mosquito fleet plying Bass Strait was laden with garrulous Van Diemen’s Land diggers. No shipping records place John or James Elmer among them.[13] A tour of the Victorian goldfields would have guaranteed the Elmers a familiarity with the appearance of alluvial gold and the conditions under which it was found. But it seems they stayed home keeping sheep and saving their pennies to take up a tenant farm at Cheshunt.[14]

A deathbed confession

John Elmer died as a supposedly senile 78-year-old at Bridgenorth, West Tamar in 1880.[15] On his deathbed he told James that at Woolnorth he’d done more than keep tigers from the sheep, having found ‘plenty of gold’.[16] The question of how exactly a Suffolk shepherd could have recognised gold a decade or two before the global gold bonanza began doesn’t seem to have fazed James. Nor did his father’s prescribed senility. Then there was the matter of why John Elmer—assuming he was literate—hadn’t exploited the reef himself by, for starters, sending rock samples to an assayer or a geologist. James’ problem was that he had developed a touch of gold fever, which is exactly what happened when you hung around with that ne’er-do-well Henry Weeks.

Chief Chummy’s gold chaser Henry Weeks. Courtesy of John Watts.

Henry Weeks and Chummy’s gold

Native Rock farmer Weeks (1832–99) was a staunch Rechabite.[17] His weakness didn’t come in a bottle but with a geological pick: he lost his nut to mineral prospecting and mining investment. Weeks had also missed the Victorian gold rushes, only arriving in Van Diemen’s Land from Monmouth, Wales, as an assisted immigrant coalminer in 1854.[18] He must have made up for lost time. Weeks’ discovery of the rich Mount Claude (Round Hill) galena mine in 1881 distracted him from the farm but did nothing for his bank balance.[19] Chasing Chummy’s gold didn’t help much either. This Lasseter’s Reef story involved George ‘Chummy’ Webb finding a fabulous gold reef in the Forth River high country—and taking the location to the grave with him, leaving his mate Henry Weeks to rediscover it. The only surviving clue to the site, ‘with the Western Tiers behind you and Cradle in front of you’, led all comers on a merry dance.[20]

The VDL Co goes mining

Weeks wasn’t alone in taking this tack. Frustrated by poor farming returns and tantalised by rich metal discoveries just outside its property, in 1882 the VDL Co began to examine its holdings for minerals.[21] Weeks or James Elmer evidently got wind of this, and with Henry Cooper put their names to a proposal to the company. The spelling is James Elmer’s:

‘I have been told that you want some party to prospect the companys land at Woolnorth if so we wold like to take the work, as have some knowledge of the place and my Father found gold thare fifty years ago and when he was dyen he told me as near as he cold were it was. My Father was shepherd there for manney years. I was down thare some few years ago and my mates got tired before we got thare and wold not stay when we got thare so wold not stop we are astickon [sic] party now thare are three of us but only two will be abell to go at a time. If you will let me know what terms we will try and agree as we wold mutch like to go down and find the big reef for thare is plenty of gold down there. We have all had a deal of practice in mining fore gold …’[22]

No VDL Co response has been found. After decades of dealing with mostly lackadaisical prospectors, VDL Co local agent James Norton Smith probably never took Elmer’s proposal seriously. The company’s prospector, a Cornishman named James Rowe, later found nothing of value at Woolnorth or any other VDL Co property, advising it to give up prospecting.[23]

Chummy keeps his secret

James Elmer didn’t give up. He still had the bug two decades later as a 70-year-old, repeating his father’s tale to Norton Smith’s successor Andrew Kidd McGaw:

‘I wold like to go and see if I cold find it. I wold have to drive down and cannot walk as I cold 50 years ago but am [not] a crippel yet. My horse wold do on the run aney ware so long as I got my tucker down. If I can go I will call and see you as am goen down I wold like to go soon …’[24]

This time James Elmer got there. The Woolnorth farm diary records that on 7 January 1906 Edward J Elmer and son arrived at Woolnorth to go prospecting, leaving nine days later.[25] There was no report of a gold strike.

Chummy also kept his secret. Camped near Bonds Peak in 1918 on a Chummy’s gold mission, Bill Johnson even believed he heard Henry Weeks’ ghost try to give him directions.[26] Hobart mining investor EC James was still searching for Chummy’s gold in the years 1925–30. James believed the gold may have been somewhere near Mount Emmett in today’s Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park.[27] Just as Harry Bell Lasseter’s central Australian mirage still triggers adventurers, revival of the Stormont Gold Mine in 2014 stirred the legend of Chummy’s gold.

No gold-bearing quartz reef is known to exist at Woolnorth. If John Elmer did find one, his discovery would pre-date that of John Gardiner (aka James Roberts), who claimed to have struck gold in a limestone quarry on Cabbage Tree Hill near latter-day Beaconsfield in 1847.[28] This has been cited as the first Tasmanian gold discovery. Gardiner only confirmed that it was gold he had found when he saw the precious metal later on a Victorian goldfield. Perhaps John Elmer had a similar eureka moment years down the track from his Woolnorth days, at Mangana, Mathinna, Lefroy or Beaconsfield, when the spirt was still willing but the body wasn’t up for the rigours of a gold rush.

[1] Harry Lasseter (aka Lewis Hubert Lasseter) died trying to relocate his fabled gold reef in central Australia in 1931.

[2] See Nic Haygarth, ‘SB Emmett: a pioneer Tasmanian prospector, from Bendigo to Balfour’, Circular Head Local History Journal, vol.1, no.1, 2004, pp.36–69.

[3] FHL film no.950448, sourced through Ancestry.com.au.

[4] CSO1/1/591/13412; GO1/1/13, p.517; Edward Curr to Samuel Reeves, 30 March 1832, VDL23/1/5 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA).

[5] ‘Our Own Reporter’ (Stuart Sanderson), ‘The VDL—VIII’, Advocate, 22 December 1925, p.12; Edward Curr to Samuel Reeves, 12 January and 25 September 1832, VDL23/1/4 and VDL23/1/5 respectively; Edward Curr to John Hicks Hutchinson, 11 April 1833, VDL178/1/1 (TA).

[6] Edward Curr to the Court of Directors, VDL Co, London, Outward Dispatch no,230, 15 October 1832, VDL5/1/4 (TA).

[7] John Hicks Hutchinson to Samuel Reeves, 8 November 1834, VDL23/1/6 (TA).

[8] Monthly returns Woolnorth Estate, VDL62/1/1 (TA).

[9] Paylists for Woolnorth, VDL 82/1/1 (TA).

[10] John Elmer was declared insolvent on 15 April 1844 while working as a butcher in Launceston (advert, Launceston Examiner, 17 April 1844, p.5). William Archer was the informant for the birth of Henry Thomas Elmer to John Elmer and Frances Kemp on 31 July 1844, birth record no.410/1844, registered at Launceston, RGD33/1/23 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=frances&qu=kemp&rw=24&isd=true#, accessed 1 July 2023.

[11] William Archer IV diary, 11 July 1851 (University of Tasmania Special Collections, Afterwards UTas).

[12] He was presumably the baby born in October 1835. See Edward Curr to Adolphus Schayer, 28 September 1835, VDL23/1/6 (TA).

[13] Another John Elmer, a free immigrant who arrived in the colony on the Water Witch, departed from Launceston for Melbourne on the brig William Hill on 27 April 1852 (POL220/1/2, p.13, TA). John E Elmer, a free arrival in the colony on the Bee, also sailed from Launceston to Melbourne on the steamer Clarence on 16 November 1852 (POL220/1/2, p.238, TA).

[14] By 1862 both John and James Elmer were tenant farmers on Cheshunt, leasing 170 and 150 acres respectively, William Archer IV diary, 15 April 1862 (UTas).

[15] Died 6 June 1880, death record no.861/1880, registered at Westbury, RGD35/1/49 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=elmer, accessed 1 July 2023; ‘Another old colonist gone’, Launceston Examiner, 9 June 1880, p.2.

[16] James Elmer, Henry Weeks and Henry Cooper to James Norton Smith, VDL Co, 12 June 1883, VDL22/1/11; James Elmer, Kimberley, to Andrew Kidd McGaw, VDL Co, 17 December 1905, VDL22/1/36 (TA).

[17] The Independent Order of Rechabites was a friendly society which encouraged abstention from alcohol. Weeks’ property Native Rock was near latter-day Railton.

[18] Descriptive list of immigrants for the Merrington. CB7/12/1/2, book 20, p.330 (TA), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=henry&qu=weeks&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Arrivals%09Arrivals+%7C%7C+Departures%09Departures, accessed 3 March 2024. Both Henry and his wife Priscilla were literate Wesleyans. Resident Mersey–Don River coalminer Zephaniah Williams applied to bring them to the colony along with other coal-mining families to work for the Mersey Coal Company.

[19] ‘Auction sales’, North Coast Standard, 17 July 1894, p.3. Bankruptcy forced Weeks to sell four properties.

[20] See, for example, ‘Lorinna’, Daily Telegraph, 11 January 1911, p.2.

[21] See Nic Haygarth, ‘Mining the Van Diemen’s Land Company holdings 1851–1899: a case of bad luck and clever adaptation’, Journal of Australasian Mining History, vol.16, October 2018, pp.93–110.

[22] James Elmer, Henry Weeks and Henry Cooper to James Norton Smith, VDL Co, 12 June 1883, VDL22/1/11 (TA).

[23] James Rowe, ‘Report of Captain James Rowe’, 1886, VDL334/1/1 (TA).

[24] James Elmer, Kimberley, to Andrew Kidd McGaw, VDL Co, 17 December 1905, VDL22/1/36 (TA).

[25] VDL277/1/34 (TA).

[26] Graham Riley, Sheffield, interviewed 23 May 1993.

[27] EC James, ‘Forth Valley prospecting’, Mercury, 8 April 1925, p.12; EC James, ‘An old gold find’, Examiner, 18 December 1929, p.11; EC James, ‘Chumey’s [sic] claim’, Examiner, 4 February 1930, p.9.

[28] See for example ‘Gold in Tasmania’, Mercury, 27 March 1869, p.3.

by Nic Haygarth | 26/09/21 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

Stephen Spurling III (1876–1962) rode the rails and marched the mountains in his quest to snap Tasmania. Revelling in ‘bad’ weather and ‘mysterious’ light, this master photographer shot the island’s heights in Romantic splendour. His long exposures of the lower Gordon River are likely to have helped shape the reservation of its banks in 1908.[1] Snow-shoed, ear-flapped and roped to a tree, he captured Devils Gullet in winter and froze the waters of Parsons Falls. But Spurling wanted to record the full gamut of life. He was there when the whales beached, the bullock teams heaved, the apple packers boxed antipodean gold and floodwaters smashed the Duck Reach Power Station. His lens was ever ready.

Stephen Spurling III in 1913, photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

Oddly, just about the only thing Spurling didn’t snap was a sack full of thylacine heads which he claimed to have seen at the Stanley Police Station in 1902. Forty-one years after the event, Spurling wrote that he watched ‘cattlemen from a station almost on the W coast [produce] two sacks of tigers’ heads (about 20 in number) and [receive] their reward’.[2] One-hundred-and-nineteen years after the event, this claim is hard to reconcile with the records of the government thylacine bounty. It adds a puzzle to the story of the so-called Woolnorth tigermen.

The Woolnorth tigermen

About 170 thylacines were killed at the Van Diemen’s Land (VDL Co) property of Woolnorth in the years 1871–1912, mostly by the company’s tigermen—a lurid title given to the Mount Cameron West stockmen. The tigermen had a standard job description for stockmen, receiving a low wage for looking after the stock, repairing fences, burning off the runs and helping to muster the sheep and cattle. They supplemented their income by hunting kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons, ringtail and brush possums. The only departure from the normal shepherd’s duty statement was keeping a line of snares across a neck of land at Green Point—now farming land at Marrawah—where the supposedly sheep-killing thylacines were thought to enter Woolnorth. The VDL Co paid their employees a bounty of 10 shillings for a dead thylacine, which was changed to match the government thylacine bounty of £1 for an adult and 10 shillings for a juvenile introduced in 1888. To make a government bounty application the tiger killer needed to present the skin at a police station, although sometimes thylacine heads sufficed for the whole skin.

It is not easy to work out how or even whether the Woolnorth tigermen generally collected the government thylacine bounty in addition to the VDL Co bounty. It is reasonable to think that the VDL Co would have encouraged its workers to do this, since doubling the payment doubled the incentive to kill the animal on Woolnorth. However, only two men are recorded as receiving a government thylacine bounty while acting as tigerman, Arthur Nicholls (6 adults, in 1889) and Ernest Warde (1 adult, 1 juvenile, in 1904).[3] This suggests that if Woolnorth tigermen and other staff received government thylacine bounties they did so through an intermediary who fronted up at the police station on their behalf.

Charles Tasman Ford and family, PH30/1/6928 (Tasmanian Archives Office).

Charles Tasman Ford and William Bennett Collins

The most likely candidates for the job of Woolnorth proxy during the government bounty period 1888–1909 were CT (Charles Tasman) Ford and WB (William Bennett) Collins. In the years 1891–99 Ford, a mixed farmer (sheep cattle, pigs, poultry, potatoes, corn, barley, oats) based at Norwood, Forest, near Stanley, claimed 25 bounties (23 adults and 2 juveniles), placing him in the government tiger killer top ten.[4] If you include bounty payments that appear to have been wrongly recorded as CJ Ford (5 adults, 1896) and CF Ford (1 adult, 1897), his tally climbs to an even more impressive 29 adults and 2 juveniles—lodging him ahead of well-known tiger tacklers Joseph Clifford of The Marshes, Ansons River (27 adults and 2 juveniles) and Robert Stevenson of Blessington (26 adults).[5] After Ford’s death in September 1899, Stanley storekeeper Collins claimed bounties for 40 adults and 4 juveniles 1900–06, his successful bounty applications neatly dovetailing with those of Ford.[6]

William Bennett Collins (standing at back) and family, courtesy of Judy Hick.

WB Collins’ Stanley store, AV Chester photo, Weekly Courier, 25 February 1905, p.20.

Where did their combined 75 tigers come from? The biggest source of dead thylacines in the far north-west at this time was Woolnorth. Twenty-six adult tigers were taken at Woolnorth in the years 1891–99, and 44 adults in the years 1900–06, making 70 in all. Tables 1 and 2 show rough correlations between Woolnorth killings and government bounty claims made by Ford and Collins. Ford, for example, received 7 payments 1892–93, the same figure for Woolnorth, while in the years 1894–97 his figure was 13 adults and theirs 16. Similarly (see Table 2), Collins claimed 16 adult and 4 juvenile bounties in 1900, a year in which 22 adult tigers were killed at Woolnorth; while in 1901 the comparative figures were 17 and 9. (Some of the data for Woolnorth is skewed by being recorded only in annual statements, which makes it look as though most tigers were killed in December. This was not the case: the December figures represent killings over the course of the whole year.) Clearly the Woolnorth tigers did not represent all the bounties claimed by Ford and Collins, but likely these made up the majority of their claims.

Table 1: CT Ford bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1891–99

| CT Ford |

29 – 2 |

Woolnorth |

26 – 0 |

| 31 July 1891 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 21 July 1892 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 9 Jany 1893 |

1 adult |

31 Dec 1892 |

2 adults |

| 27 April 1893 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 5 May 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 19 June 1893 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 24 July 1893 |

1 adult |

18 Dec 1893 |

5 adults |

| 23 Jany 1894 |

2 adults |

20 Dec 1894 |

3 adults |

| 24 Feby 1896 |

5 adults |

30 Dec 1895 |

4 adults |

| 5 March 1897 |

1 adult |

7 Jany 1896 |

2 adults |

| 22 Sept 1897 |

3 adults |

19 Dec 1896 |

3 adults |

| 4 Nov 1897 |

2 adults |

Dec 1897 |

4 adults |

| 1 Feby 1898 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 2 August 1898 |

2 adults |

Dec 1898 |

3 adults |

| 30 May 1899 |

1 adult |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 30 Aug 1899 |

2 young |

|

|

Table 2: WB Collins bounty claims compared to Woolnorth tiger kills 1900–12

| WB Collins |

40 – 4 |

Woolnorth |

44 |

| 27 Feby 1900 |

3 adults |

|

|

| 16 Aug 1900 |

5 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1900 |

4 adults |

|

|

| 15 Nov 1900 |

4 adults, 4 young |

Dec 1900 |

22 adults |

| 13 Mar 1901 |

2 adults |

|

|

| 31 July 1901 |

7 adults |

|

|

| 28 Aug 1901 |

6 adults |

|

|

| 3 Oct 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1901 |

9 adults |

| 5 Nov 1901 |

1 adult |

Dec 1902 |

3 adults |

| 7 May 1903 |

2 adults |

Nov 1903 |

8 adults |

| 17 Nov 1903 |

4 adults |

1904 |

1 adult, 1 young (Warde) |

| 21 June 1906 |

1 adult |

1906 |

1 adult |

It would not have been difficult for Ford to act as a go-between for Woolnorth workers.[7] He had grazing land at Montagu and Marrawah/South Downs, east and south of Woolnorth respectively, and would have travelled via Woolnorth to reach the latter. He was also a supplier of cattle and other produce to Zeehan, a wheeler and dealer who bought up Circular Head produce to add to his consignments of livestock to the West Coast.[8] It would have been a simple thing for him on his way home from a Zeehan cattle drive to collect native animal skins and tiger skins/heads from the homestead at Woolnorth, presumably taking a commission for himself in his role as intermediary.

Of course that is not the only possible explanation for Ford’s bounty payments. His brothers Henry Flinders (Harry) Ford (three adults) and William Wilbraham Ford (6 adults) both claimed thylacine bounties. They had a cattle run at Sandy Cape, while William had another station at Whales Head (Temma) on the West Coast stock route.[9] It is possible that all the Ford government thylacine bounty payments represented tigers killed on their own grazing runs and/or in the course of West Coast cattle drives. CT Ford did, after all, take up land at Green Point, the place where the VDL Co killed most of its tigers in the nineteenth century. However, if the Fords killed a lot of tigers on their own properties or during cattle drives you would expect to see some evidence for it, such as in newspaper reports or letters. The Fords were, after all, not only VDL Co manager James Norton Smith’s in-laws, but variously his tenants, neighbours and fellow cattlemen. No evidence has been found in VDL Co correspondence. Oddly, when CT Ford shot himself at home in 1899, it was reported to police by his supposed employee George Wainwright—the same name as the Woolnorth tigerman of that time.[10] Perhaps this was the tigerman’s son George Wainwright junior, who would then have been about sixteen years old, and if so it shows that tigerman and presumed proxy bounty collector knew each other.

For all his 44 bounty claims, storekeeper WB Collins possibly never saw a living thylacine, let alone killed one. After Ford’s death, Collins appears to have established an on-going relationship with Woolnorth, being paid for three bounties in February 1900 before his store even opened for business. The VDL Co correspondence contains plenty of evidence that Collins dealt regularly with Woolnorth as a supplier and skins dealer.

The puzzle of Spurling’s sack of tiger heads

The only problem is Spurling. His claim about the 20 tiger heads being presented to the Stanley Police as a bounty claim doesn’t make a lot of sense. There is no record of such an event in the Stanley Police Station books, although, admittedly, tiger bounty payments rarely turn up in police station duty books or daily records of crime occurrences.[11] Still, 20 bounty claims presented at once would constitute a noteworthy event. The ‘almost W coast’ cattle station to which Spurling referred can only have been Woolnorth or a farm south of there, but his recollection seems wildly inaccurate..

If we assume Spurling got the year right, 1902, we can try to fix on an approximate date for his sack of tiger heads. Spurling photos of Stanley appeared in the Weekly Courier newspaper on 26 April 1902. If we assume that taking these photos provided the occasion for the photographer to meet the tiger heads, we are confined to government bounty payments for the first four months of that year. Less than 20 bounties were paid across Tasmania during that time, and there were no bulk payments of the kind described by Spurling—nor did any bulk payments occur at any time during the year 1902.

Did Spurling get the year wrong? If the 20 heads came from Woolnorth and were supplied in bulk, the time was probably late 1900, the first year in decades in which more than 20 tigers were taken there. Did Spurling see someone from Collins’ store bring in heads from Woolnorth? Not even that seems likely. In February 1900 Collins collected bounties for three adult thylacines; another 5 adults followed in July; in September he collected on another 4; and in October he presented 4 adults and 4 cubs: 20 animals in all, spread over a period of eight months, not in one hit.[12] Saving those 20 heads secured over a period of months for presentation in one hit would be a—frankly—disgusting task given their inevitable state of putrefaction. Spurling’s sack of heads didn’t represent Collins or Woolnorth. No one—no bounty applicant from any part of Tasmania, let alone a group of Woolnorth employees—was ever paid 20 bounties in one hit. The basis of his claim remains a mystery.

[1] See Nic Haygarth, Wonderstruck: treasuring Tasmania’s caves and karst, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.63–69.

[2] Stephen Spurling III, ‘The Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus’, Journal of the Bengal Natural History Society, vol.XVIII, no,2, October 1943, p.56.

[3] Nicholls: bounties no.289, 14 January 1889, p.127 (4 adults); and no.126, 29 April 1889, p.133 (2 adults), LSD247/1/1. Warde: bounty no.190, 20 October 1904 (1 adult and 1 juvenile), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[4] Bounties no.365, 31 July 1891 (2 adults); no.204, 21 July 1892, LSD247/1/1; no.402, 9 January 1893; no.71, 27 April 1893 (2 adults); no.91, 5 May 1893; no.125, 19 June 1893; no.183, 24 July 1893, no.4, 23 January 1894 (2 adults); no.239, 22 September 1897 (3 adults, ‘August 2’); no.276, 4 November 1897 (2 adults, ’27 October’); no.379, 1 February 1898 (‘4 December’); no.191, 2 August 1898 (2 adults, ‘7 July’); no.158, 30 May 1899 (’26 May’); no.253, 30 August 1899 (3 adults, ’24 August’); no.254, 30 August 1899 (2 juveniles, ‘24 August’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[5] Bounties no.304, 24 February 1896 (5 adults); and no.37, 5 March 1897, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[6] Bounties no.43, 27 February 1900 (3 adults, ’22 February’); no.250, 16 August 1900 (5 adults, ’26 July’); no.316, 3 October 1900 (4 adults, ’27 September’); no.398, 15 November 1900 (4 adults and 4 juveniles, ’28 October’); no.79, 13 March 1901 (2 adults, ’28 February’); no.340, 31 July 1901 (7 adults, ’25 July’); no.393, 28 August 1901 (6 adults, ‘2/3 August’); no.448, 3 October 1901 (’26 September’); no.509, 5 November 1901 (’24 October 1901’); no.218, 7 May 1903 (2 adults, ’24 April’); no.724, 17 November 1903 (4 adults); no.581, 21 June 1906, LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[7] Woolnorth farm journals, VDL277/1/1–33 (TAHO). The Woolnorth figure for 1900–06 excludes one adult and one juvenile killed by Ernest Warde and for which he claimed the government bounty payment himself (bounty no.190, 20 October 1904, LSD247/1/2 [TAHO]).

[8] ‘Circular Head harvest prospects’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 19 January 1895, p.2.

[9] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1898, p.184; 1899, p.305.

[10] 10 September 1899, Daily record of crime occurrences, Stanley Police Station, POL93/1/1 (TAHO).

[11] Stanley Police Station duty book, POL92/1/1; Daily record of crime occurrences, POL93/1/1 (TAHO). Daily records of crime occurrences often include information not of a criminal nature.

[12] Bounties no.43, 22 February 1900 (three adults); no.250, 16 August 1900 (five adults); no.316, 27 September 1900 (four adults); and no.398, 28 October 1900 (four adults and four juveniles), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 22/10/20 | Circular Head history, Story of the thylacine

By the 1890s farmers like Joseph Clifford and Robert Stevenson were effectively adding Tasmanian tiger farming to their portfolios of raising stock, growing crops and hunting. Since thylacines appeared on their property, they made a conscious effort to catch them alive in a footer snare or pit rather than dead in a necker snare. A tiger grew no valuable wool, but in 1890 a live wether might fetch 13 shillings, compared to £6 for an adult thylacine delivered to Sydney.[1] A dead adult thylacine, on the other hand, was worth only £1 under the government bounty scheme.

The problem with these special efforts to catch tigers alive was that hunters only had a certain amount of control over what animals ended up in their snares or pits. Twentieth-century hunters often complained about city regulators who thought it feasible to close the season on brush possum but open it for wallabies and pademelons. Inevitably, hunters caught some brush possum in their wallaby and pademelon snares during the course of the season, which could land them a hefty fine in court unless they destroyed the precious but unlawful skins.[2] John Pearce junior in the upper Derwent district claimed that he and his brothers caught seventeen tigers in ‘special neck snares’ set alongside their kangaroo snares.[3] How did the tigers recognise the ‘special neck snares’ provided for their specific use? All you could do was vary the height of the necker snare to catch the desired animal’s head as it walked. Too bad if something else stuck its head in the noose. Wombats, for example, were a hazard. Gustav Weindorfer of Cradle Valley set snares at the right height to catch Bennett’s wallabies by the neck, but also caught wombats in them.[4] Wombats were good for ‘badger’ stew and for hearth mats but the skins had no value. Robert Stevenson of Aplico, Blessington, caught wombats alive in his tiger pits—which they then set about destroying by burrowing their way out.[5]

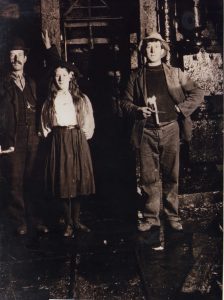

George Wainwright senior, Matilda Wainwright and children at Mount Cameron West (Preminghana) c1900. Courtesy of Kath Medwin.

These problems aside, it seems odd that the pragmatic Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co), which later added fur hunting to its income stream, didn’t cotton on to the live tiger trade. They could have followed the example of George Wainwright senior, who sold a Woolnorth tiger to Fitzgerald’s Circus in 1896.[6] In 1900, for example, 22 thylacines were killed on Woolnorth, a potential income of more than £100 had the animals been taken alive. Even when, later, four living Woolnorth tigers were sold, the money stayed with the employees, with the VDL Co not even taking a commission. (It should be noted that four young tigers caught by Walter Pinkard on Woolnorth in 1901 were not accounted for in bounty payments.[7] It is possible that they were sold alive—but there are no records of a sale or even correspondence about the animals. Their fate is unknown.)

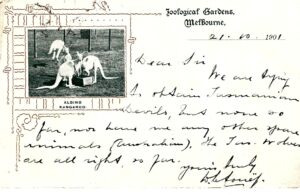

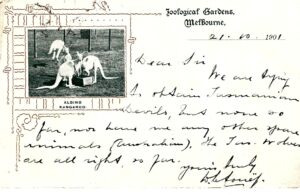

William Le Souef to Kruger, 22 October 1901: ‘The Tasmanian Wolves are all

right, so far’. Did he get them from Woolnorth? Postcard courtesy of Mike Simco.

The VDL Co’s failure to exploit the live trade for its perceived arch enemy can possibly be explained by the tunnel vision of its directors and departing Tasmanian agent and the inexperience of his successor. James Norton Smith resigned as local manager in 1902. His replacement, Scotsman Andrew Kidd (AK) McGaw, harnessed Norton Smith’s 33-year corporate knowledge by re-engaging him as farm manager. It would not have been easy for McGaw to learn the ropes in a new country, among business associates cultivated by his predecessor, and the re-engagement of Norton Smith as his second allowed him to transition into the manager position. As would be expected, McGaw stamped his authority on the agency by criticising some of Norton Smith’s policies and distancing himself from them.[8] Ahead of Ernest Warde’s engagement as ‘tigerman’, the VDL Co’s shepherd at Mount Cameron West, he scrapped Norton Smith’s recent bounty incentive scheme of £2 for a tiger killed by a man out hunting with dogs.

Woolnorth, showing main property features and the original boundary. Base map courtesy of DPIPWE.

After Warde’s departure in 1905, the tiger snares at Mount Cameron and Studland Bay were checked intermittently. Woolnorth overseer Thomas Lovell killed a tiger at Studland Bay in 1906, but the number of tigers and dogs reported on the property was now negligible.[9] This reflected the statewide situation, with only eighteen government thylacine bounties being paid in 1907, and only thirteen in 1908.[10]

However, the value of live tigers continued to climb as they became rarer. The first documented approach to the VDL Co for live tigers came in July 1902 from AS Le Souef of the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne, who offered £8 for a pair of adults and £5 for a pair of juveniles. He also wanted devils and tiger cats, in response to which George Wainwright junior supplied two tiger cats (spotted quolls, Dasyurus maculatus).[11] Given the tiger’s reputation as a sheep killer, native animal farming might have been a hard sell to the directors, and the company continued to use necker snares which were generally fatal to thylacines. What price would it take to change that behaviour? In July 1908 McGaw read a newspaper advertisement:

‘WANTED—Five Tasmanian tigers, handsome price for good specimens. Apply Beaumaris, Hobart.’[12]

He discovered that the proprietor of the private Beaumaris Zoo at Battery Point, Mary Grant Roberts, wanted a pair of living tigers immediately to freight to the London Zoo.[13] The Orient steamer Ortona was departing for London at the end of the month. She offered McGaw £10 for a living, uninjured pair of adults. Roberts hoped to secure the tiger caught recently by George Tripp at Watery Plains, but felt that she was competing for live captures with William McGowan of the City Park Zoo, Launceston, who advertised in the same month.[14] Eroni Brothers Circus was also in the market for living tigers.[15]

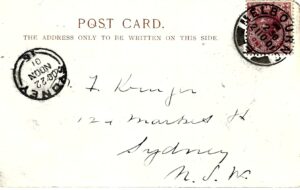

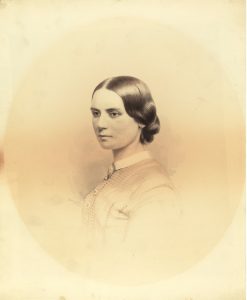

A young Mary Grant Roberts, from NS823/1/69 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

Almost as Roberts made her offer, George Wainwright junior tracked a tiger at Mount Cameron West, but it evaded capture.[16] In the meantime Roberts was able to secure her first thylacine from the Dee River.[17]

Almost a year passed before the chance arose for the VDL Co do business, when in May 1909 Wainwright retrieved a three-quarters-grown male tiger uninjured from a necker snare.[18] Perhaps not appreciating the tiger’s youth, Roberts offered £5 plus the rail freight from either Burnie or Launceston. She wanted the animal delivered to her in Hobart within ten days in order to ship it to the London Zoo on the Persic. It would thereby replace one which had died of heat exhaustion in transit to the same destination a few months earlier.[19]

However, the overseer of a remote stock station could not meet that deadline. The delay came with a bonus—the capture of three more members of the first tiger’s family, his sisters and mother.[20] Bob Wainwright recalled his stepfather Thomas Lovell and brother George placing the animals in a cage. There was also a familiar story of tigers refusing to eat dead game: ‘They had to catch a live wallaby and throw it in, alive, and then they [the thylacines] killed it’.[21] With McGaw continuing to act as intermediary between buyer and supplier, a price of £15 was settled on for the family of four.[22]

Roberts and McGaw communicated as social equals, but their social inferiors—hunters, stockmen and an overseer—were not named in their correspondence. This made for frustrating reading when Roberts discussed hunters (‘the man’) with whom she was dealing over live tigers. She had been expecting to receive two young tigers from a Hamilton hunter for her own zoo, but these had now died, causing her to reconsider her plans for the Woolnorth family.[23]

The mother thylacine (centre) and her three young captured at Woolnorth in 1909. W Williamson photo from the Tasmanian Mail, 25 May 1916, p.18.

It wasn’t until the first week in July 1909 that the auxiliary ketch Gladys bore the crate of thylacines to Burnie, where they began the train journey to Hobart.[24] A week later they were said to be thriving in captivity.[25] Roberts was so pleased with the animals’ progress that after eight months she sent a postal order to Lovell and Wainwright as a mark of appreciation. She was impressed with the mother’s devotion to her young, believing that the death of the two Hamilton cubs was attributable to their mother’s absence.[26] However, money was becoming a concern. Buying all the tigers’ feed from a butcher was expensive, and when she received a potentially lucrative order for a tiger from a New York Zoo, she found the cost of insuring the animal over such a long journey prohibitive. On 1 March 1910 she ‘very reluctantly’ broke up the family group by dispatching the young male to the London Zoo. ‘I am keeping on the two [other juveniles]’, she wrote, ‘in the hope that they may breed, and the mother all along has been very happy with the three young ones’.[27]

Roberts was now offering £10 per adult thylacine—but there was none to sell at Woolnorth. Seventeen months later she paid Power £12 10s for his large tiger from Tyenna, and scored £30 shipping to London the last of the three young from the 1909 family group.[28] Her tiger breeding program was over, probably defeated by economics—but what might have been the rewards for perseverance? Perhaps she would have been the greatest tiger farmer of all.

[1] See, for example, ‘Commercial’, Mercury, 5 August 1890, p.2; Sarah Mitchell diary, 9 June 1890, RS32/20, Royal Society Collection (University of Tasmania Archives).

[2] See, for example, ‘Trappers fined’, Advocate, 22 October 1943, p.4.

[3] ‘Direct communication with the west coast initiated’, Mercury, 1 September 1932, p.12.

[4] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Journal of the Victorian Naturalists Society, vol.36, March 1920, p.159.

[5] Lewis Stevenson, interviewed by Bob Brown, 1 December 1972 (QVMAG).

[6] ‘Circular Head notes’, Wellington Times and Agricultural and Mining Gazette, 25 June 1896, p.2.

[7] Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 19 July 1901, VDL22/1/27 (TAHO).

[8] In Outward Despatch no.46, 4 January 1904, p.366, McGaw criticised Norton Smith for not doing more to arrest the encroachment of sand at Studland Bay and Mount Cameron (VDL7/1/13).

[9] Woolnorth farm diary, 30 September 1906 (VDL277/1/34). This VDL Co bounty was not paid until the following year (December 1907, p.95, VDL129/1/4). C Wilson was paid for killing two dogs found worrying sheep in 1906 (December 1906, p.58, VDL129/1/4 (TAHO).

[10] See thylacine bounty payment records in LSD247/1/3 (TAHO).

[11] AS Le Souef to James Norton Smith, 11 July 1902; Walter Pinkard to James Norton Smith, 4 August 1902, VDL22/1/28 (TAHO).

[12] ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 July 1908, p.3.

[13] For Roberts, see Robert Paddle, ‘The most photographed of thylacines: Mary Roberts’ Tyenna male—including a response to Freeman (2005) and a farewell to Laird (1968)’, Australian Zoologist, vol.34, no.4, January 2008, pp.459–70.

[14] In ‘Wanted to buy’, Mercury, 18 July 1908, p.2, McGowan asked for tigers ‘dead or alive’. He had also advertised for ‘tigers … good, sound specimens, high price; also 2 or 3 dead or damaged specimens’ in the previous year (‘Wanted’, Mercury, 21 June 1907, p.2). George Tripp’s tiger must have died before it could be sold alive, since he claimed a government bounty for it (no.35, 25 July 1908, LSD247/1/3 [TAHO]).

[15] See, for example, ‘Wanted’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 7 March 1908, p.6.

[16] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 17 July 1908, VDL22/1/34 (TAHO).

[17] ‘The Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 7 October 1908, p.4.

[18] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 24 May 1909, VDL22/135 (TAHO). This thylacine was originally thought to be a young female, but McGaw later stated that it was a young male.

[19] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 31 May 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[20] Thomas Lovell to AK McGaw, 1 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[21] Bob Wainwright, 86 years old, interviewed in Launceston, 27 October 1980.

[22] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 9 June 1909, VDL52/1/29; Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 10 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[23] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 21 June 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[24] AK McGaw to Mary G Roberts, 7 July 1909, VDL52/1/29 (TAHO); ‘Stanley’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 6 July 1909, p.2.

[25] W Roberts to AK McGaw, 15 July 1909, VDL22/1/35 (TAHO).

[26] In May 1912 she received two young tigers from buyer EJ Sidebottom in Launceston, paying him £20 in the belief that they were adults. They died three days later (Mary Grant Roberts diary, 6, 7 and 10 May 1912, NS823/1/8 [TAHO]).

[27] Mary G Roberts to AK McGaw, 14 March 1910, VDL22/1/36 (TAHO).

[28] Mary Grant Roberts diary, 12 August, 26 September and 24 December 1911, NS823/1/8 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 13/02/17 | Circular Head history, Tasmanian high country history

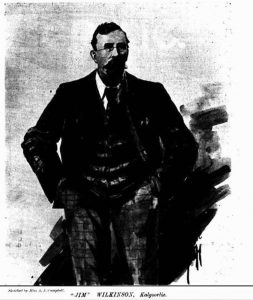

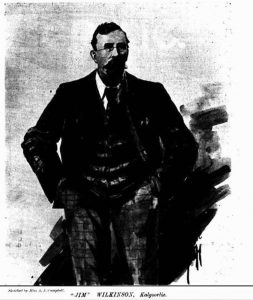

‘Big Jim’ Wilkinson, sketched by Miss AJ Campbell at Kalgoorlie in 1898. From Critic (Adelaide), 26 March 1898, p.5

A heartbreaking dedication is inscribed on a ceramic vase on one of the four marked graves in the Balfour Cemetery:

To Jim

good night love

may the night be short

that parts we two

Alma

Big Jim Wilkinson stood almost 200 cm tall—6 foot 5 inches in the old measure. He was proof that even remote Tasmanian mining fields attracted not just local prospectors, labourers, miners, engine drivers and other skilled workers, but international adventurers, men who flitted between gold rushes and boom towns, revelling in the lifestyle, but who eventually settled into the more stable support industries that underpinned every mining field. Wilkinson, who supposedly counted Australia’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton, and the poet, Adam Lindsay Gordon, as friends, had been an imposing figure on the Kalgoorlie goldfield, being ‘a big power with the miners … He is one of the most popular men in Kalgoorlie, and deservedly so. He has a head like a Roman senator…’[1] He hadn’t quite made it into the Australian Senate, being defeated in two campaigns in Western Australia. He was also said to have made ‘a prodigious impression’ in Gormanston, ‘with his Uncle Sam beard, his diamonds, his earrings, and his accent which was very good American for a Victorian native!’[2] He had discovered gold on the Murchison field, kept livery stables and attained legendary status as a coach driver in the early days of the Silverton-Broken Hill silver field by keeping his passengers—or his horses, if he was carrying only freight—awake through the night with recitations of Gordon’s verses.[3] He had been a pearler, a guano dealer in south-east Asia, a race handicapper and a hotelier.[4]

Alma’s inscription on Jim’s grave at Balfour.

Photo by Nic Haygarth.

However, none of that counted for anything at Balfour, where Wilkinson achieved another distinction entirely—he was the first interment in the cemetery, in January 1910, after only one month in town. He had come to Balfour to run a hotel for his brother-in-law, the ubiquitous jack-of-all-trades Frank Gaffney. Wilkinson arrived as a diabetic, in a shanty town that had no resident doctor.[5] Nor was there a minister to officiate at his grave. Like typhoid victims Haywood and Tom Shepherd before him, he died when there was no tramway from Temma. His grave relics—with their emphatic tale of loss and devotion—must have been hauled in from Temma by horsepower at least a year after his death. For more than a century, Big Jim Wilkinson, bright star of the boom-time, has rested in obscurity on one of Australia’s most obscure mining fields, leaving us to ponder the levelling power of death and the burning question—who was Alma?

*With thanks to Val Fleming.

[1] ‘Language freaks’, Critic (Adelaide), 26 March 1898, p.5.

[2] ‘Gormanston notes’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 27 October 1903, p.4.

[3] See, for example, Randolph Bedford, Naught to thirty three, Currawong Press, Sydney, 1944, pp.98–100.

[4] See, for example, ‘Death of Mr JJ Wilkinson’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus, 1 November 1910, p.15.

[5] ‘Resident doctor’, Examiner, 10 January 1910, p.5.

by Nic Haygarth | 09/01/17 | Circular Head history, Tasmanian high country history

Sylvia McArthur’s slab in the ground litter at Balfour.

Grave of William Murray. Photo by Val Fleming.

The story of Balfour is told by two graves in a highland cemetery in north-western Tasmania. For more than a century, lying side by side, William Murray and Sylvia McArthur have been fixed silently in their interlocking roles in what historian Geoffrey Blainey called the ‘Indian summer’ of Tasmania’s first mining boom.

There is an interesting dynamic between these two people, who were interred on consecutive days in November 1912. William Murray was a 51-year-old husband and father of two, Sylvia McArthur a 15-year-old schoolgirl. He has Doric columns on his granite headstone, which is reputed to have been sent out from Scotland. She has a slab from J Dunn and Co, Launceston, and, as their graves suggest, they represented different social strata. As one of the owners of the principal mine, the Copper (Murrays’) Reward, William Murray was from the big end of town, living in what was once called ‘the mansion’. Sylvia McArthur was part of the globe-trotting fraternity of mine workers, the community that follows the speculators, grounded in the realities of remote mining towns a century ago, physical and cultural isolation, poor sanitation and health care. Sylvia would have lived in a corrugated iron hut, one of those described as looking like ‘opened out sardine cans’.[1] She is believed to have died of typhoid. William Murray died by putting a gun to his temple, reputedly because of financial and marital collapse stemming from the Copper Reward mine.[2] So, in different ways, they were both casualties of Balfour’s frenzied mining speculation.

Sylvia McArthur’s story begins with the marriage of William McArthur, one of nine children born to Scottish bounty immigrants, to Catherine Dolan, the daughter of Cygnet farmers.[3] They married in Zeehan, where he was a miner and she a housemaid.[4] Two of William’s brothers, Robert and John, likewise followed the mining profession wherever there was work.[5] At Zeehan in 1897 Catherine produced their second daughter, Sylvia Iris McArthur.[6] Emphatic endorsements of the Mount Lyell copper boom were then rising in Queenstown, Strahan and Zeehan. Built on a grand scale in 1898, Zeehan’s Gaiety Theatre and Grand Hotel had a stage larger than that of Hobart’s Theatre Royal and more seating than Hobart’s Town Hall.[7] Zeehan’s silver mines had also peaked, but the field was beset by shallow lodes and problems of ore treatment.

Catherine and William McArthur at Zeehan with their first three daughters, Florence, Sylvia and Gladys. Mora Studio, Zeehan, photo courtesy of Edie McArthur.

Tragically, in 1904 Catherine McArthur died after a short illness at the age of only 27, moving her husband to verse:

‘Tis hard to break the tender cord,

When love has bound the heart.

Tis hard, so hard, to speak the words:

We for a time must part.

Dearest love, we have laid thee

In the peaceful grave’s embrace,

But they memory will be cherished,

Till we see thy heavenly face’.[8]

By 1908, when William re-married, and with 20-year-old Marion May Delaney started adding boys to his four girls, Zeehan was in decline.[9]

The Balfour coach negotiating a sand dune. Photo by Fritz Noetling from the Tasmanian Mail, 9 March 1911, p.24.

The new boom town was Balfour. It was remote even by mining field standards, a shanty town lodged somewhere between Circular Head and the ‘true’ west coast. No road, railway or deep-water port served it. The Balfour coach could be bogged in beach sand or swamped by the Southern Ocean. Yet by the spring of 1909, investors were agog at the 1100 tons of ore, averaging about 30% copper, which the brothers William and Tom Murray had somehow dispatched to market. In October 1909 a report circulated that the Murrays had sold their Copper Reward mine for £50,000—a claim they denied.[10] The Balfour copper field was soon being hailed as a second Mount Lyell.[11]

By October 1911 William McArthur had secured the position of engine driver at the Copper Reward. It took his family a fortnight’s travel from Zeehan via Burnie and Stanley to join him at Balfour. Rough weather held up their voyage on the ketch HJH, forcing passengers ashore five kilometres from the Woolnorth stock station. Finally, a four-hour ride on the new horse-drawn Temma-Balfour tramway delivered the family to its remote new home.[12]

Balfour had already suffered the obligatory typhoid epidemic of the early life of a mining town by the time fourteen-year-old Sylvia McArthur arrived. The Circular Head Council apparently did not take much notice of this, because it afterwards suggested to the Balfour Advisory Board that it dump the town’s nightsoil in the Frankland River, presumably downstream of the local recreational area and fishing hole.[13] A sanitary inspector despatched to Balfour after the typhoid outbreak found only one unsanitary drain at the Balfour Hotel, plus the suspicion that a pig was being kept on that premises—apparently in anticipation of King George V’s coronation in June 1911, when it was patriotically sacrificed.[14]

William Murray was out of town at that time. Having taken an eighteen-year-old bride, the forty-eight-year-old was honeymooning in England.[15] In August 1911, when Hazel and baby Jean Murray saw Balfour for the first time, they took up residence in what one man called the ‘mansion’, perhaps the only house in town blueprinted by an architect.[16] Perhaps the Murrays also had acetylene lighting, which would have placed them ahead of the underground miners in the candle-lit Copper Reward.

The McArthur family and friends on the Frankland River bridge, with Sylvia at back (left) in the wide-brimmed hat. William McArthur photo from the Weekly Courier, 18 April 1912, p.17.

The same picnic party at the river. William McArthur photo from the Weekly Courier, 18 April 1912, p.17.

The McArthurs began to live their life in the social pages in January 1912, when Sylvia wrote her first letter to the Weekly Courier newspaper. It is through her words and her father’s photos that we get the story of everyday life in a remote settlement. Sylvia went from a very large school at Zeehan to a one-teacher operation of 23 students at Balfour. She stopped attending because there were no girls of her own age, and she felt as lonely at school as she was at home. Instead, she carried her father’s crib to the mine and looked after her younger siblings.[17] Her sisters became schoolteachers, and Sylvia’s own love of small children is very evident. For amusement she collected postcards and read copiously. The Christmas sports and picnic was the highlight of the social calendar. There was also a dance every few months to the tune of a piano accordion. Sylvia enjoyed the fern gullies and glades of the nearby Frankland River, a favourite picnic spot where walks were taken and the blackfishing was lively.[18]

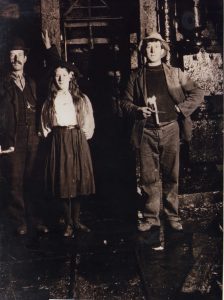

William and Sylvia McArthur pictured with an unknown man (right) underground in the Copper Reward. Photo courtesy of Edie McArthur.

One day she ventured underground at the Copper Reward. Her permanent interment underground was six months away when she looked to a future beyond the transitory mining town, one she would never know:

‘It was the first time I had been down a mine. I think it is a funny feeling one has whilst going down in a cage … Whilst I was down below a gentleman took a flashlight photograph of us. We all looked like ghosts, for our faces were so white. However, I would not like to leave Balfour without being able to say I was down a mine’.[19]

In her final letter to ‘Dame Durden’ of the Weekly Courier in October 1912, Sylvia described a concert given by the Balfour schoolchildren, illustrated, as usual, by her father’s pictures.[20] Her fatal illness may have been brewing even as the newspaper went to press.

What was William Murray’s condition? It must have been tempting for the Murrays to start living the good life that the speculation promised, and which could easily have landed them in debt. Perhaps the brothers had missed their big chance. It has been claimed that they refused an offer of £30,000 for the mine, a decision they may have come to regret.[21] William Murray shot himself in his home at Donald Street, Balfour, on 4 November 1912, reputedly as part of an unfulfilled double suicide pact with Tom.[22] Sylvia McArthur died in great pain next day ‘from a complication of complaints’ after a three-week illness.[23] She was buried overlooking the Frankland River that she loved. Her heartbroken father described the scene in the Weekly Courier:

‘For she’s sleeping on the hillside,

Where the morning sun will shine,

‘Mid a scene of ferns and dogwood,

Fringed with wild clematis vine,

With its tender fibres clinging,

Drawing close to the boughs above,

As our hearts are drawn to Sylvie,

By the tender cords of love.

And the fiercest storm in winter,

As it rages on the shore,

Will not disturb you, dearest Sylvie,

Where you sleep for evermore’.[24]

Ferns and dogwood still guard William Murray and Sylvia McArthur’s final resting-place. In fact the scrub has grown up so much that the cemetery’s river view has been lost. The ‘lonely spot near Balfour’, as William McArthur described it, is lonelier than ever.

[1] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 9 February 1910, p.3.

[2] See, for example, Heather Nimmo’s play ‘Murrays’ Reward: a play in two acts’.

[3] Thanks to Edie McArthur for help with McArthur family background. For Catherine Dolan, see birth registration no.1352/1877, Cygnet, to Thomas Dolan and Agnes Dolan, née Harrison.

[4] Marriage registration no.838/1895, Zeehan. Catherine gave her age as 18 but she was only 17; William was 28.

[5] Thanks to Edie McArthur for help with McArthur family background.

[6] She was born 16 October 1897, registration no.3194/1897, Zeehan.

[7] ‘Gaiety Theatre’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 November 1898, p.4.

[8] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 23 July 1904, p.2; memorial to Catherine McArthur, held by Edie McArthur.

[9] Marriage registration no.1389/1908, Zeehan.

[10] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 26 October, p.3; and 4 November 1911, p.2.

[11] ‘The far north-west’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 7 February 1911, p.2.

[12] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 11 January 1912, p.3.

[13] See ‘Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 21 December 1910, p.2; and 18 January 1911, p.3.

[14] For the pig suspicion and the unsanitary drain, see ‘Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 21 December 1910, p.2 and Circular Head Chronicle, 29 March 1911, p.2 respectively. For the pig slaughter, see the exchange of poems by JW Lord (‘Breheny’s pig’, Circular Head Chronicle, 21 June 1911, p.2 and 26 July 1911, p.4) and ‘Daybreak’ (Clement Lewis Gray), ‘RIP’, Circular Head Chronicle, 5 July 1911, p.3.

[15] ‘Social news’, Star (Sydney), 29 January 1910, p.16.

[16] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 9 February 1910, p.3; TB Moore diaries, 30 April 1912, ZM5641 (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery).

[17] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 13 June 1912, p.3.

[18] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young Folks’, Weekly Courier, 1 February 1912, p.3; 13 June 1912, p.3; 18 July 1912 p.3; 3 October 1912, p.3; Mavis McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young Folks’, Weekly Courier,18 July 1912, p.3.

[19] Sylvia McArthur; in ‘Dame Durden’, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 13 June 1912, p.3.

[20] Sylvia McArthur; in Dame Durden, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 3 October 1912, p.3.

[21] E Payne, ‘Balfour mine’, Examiner, 19 March 1951, p.2.

[22] The Circular Head Chronicle (‘Deaths at Balfour’, 6 November 1912, p.2) reported merely that Murray had ‘died suddenly’. The coroner found that Murray died of a self-inflicted ‘gunshot wound to the head … while of unsound mind’ (see SC195-1-82-13112, [TAHO]).

[23] She died 5 November 1912, registration no.652/1912, Montagu. See also ‘Deaths at Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 6 November 1912, p.2. The official record places her death 10 days later. No inquest was conducted.

[24] Poem by William McArthur published in Dame Durden, ‘Young folks’, Weekly Courier, 21 November 1912, p.3.

by Nic Haygarth | 08/01/17 | Circular Head history, Tasmanian high country history

The story of Balfour is told by two graves in a highland cemetery in north-western Tasmania. For more than a century, lying side by side, William Murray and Sylvia McArthur have been fixed silently in their interlocking roles in what historian Geoffrey Blainey called the ‘Indian summer’ of Tasmania’s first mining boom. Why did they ever live in this remote place?

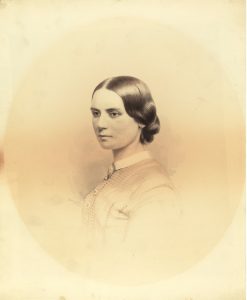

They were both casualties of frenzied speculation that Balfour would become a second Mount Lyell copper field. Part one of this story concerns William Wallace Fullarton Murray junior (1861–1912), manager of the Copper Reward (Murrays’ Reward) mine which generated this excitement. He received a fighting pedigree from both parents. William Murray’s paternal grandfather, a captain in the 91st regiment, was reputedly a hero of the Battle of Trafalgar. His father, William Wallace Fullarton Murray senior (1820–94), a Church of England minister, was brought to Tasmania from England to tutor the children of Governor Sir William Dennison, after which he served as chaplain of New Norfolk (St Matthew’s Church) for 39 years. William senior married Augusta Schaw, the sixth daughter of Major Schaw, a police magistrate formerly of the 21st Fusiliers.[1]

Such an impressive lineage demanded a private school education, which young William and his brother Thomas Charles Murray (1862–1938) received, but their upbringing, along with that of their six sisters, was relatively modest.[2] Although Tom was a mad-keen prospector, it was actually their sister Kate who led the Murray brothers to what became known as the Copper Reward mine near Mount Balfour, far from their home town of New Norfolk. Kate married William Wilbraham Ford, a Circular Head farmer, who grub-staked a prospector, Frederick Henry Smith.[3] Smith discovered copper on Tin Creek near Mount Balfour, which had been a sparsely-visited alluvial tin field for two decades. In 1901 Tom Murray helped him peg the discovery and applied for a reward claim under the Mining Act (1900). Tom and William Murray, Fred Smith and William Ford took a quarter share each in the mine, Ford apparently helping to finance and promote its development.[4] The remote claim was not surveyed until 1905, by which time Smith’s whereabouts were unknown. The lease was finally issued in 1907 to Tom Murray and in trust for others interested. Having abandoned their unprofitable gold leases at Woody Hill near Queenstown, the Murray brothers worked their reward claim continuously from February 1907.[5] To relieve financial pressure a fifth share in the mine (rumoured to be Robert Sticht, general manager of the Mount Lyell Company) was introduced.[6]

The Murrays built a farm—now known as Kaywood—with an extensive vegetable garden near the hazardous port of Whales Head (Temma). Six-horse wagons delivered ore from the mine to the brothers’ store shed at Temma, awaiting the fortnightly visits of the auxiliary ketch Gladys which bore it to market. Without even a jetty, loading and offloading at Temma involved a rowboat meeting a dray driven into the water.[7]

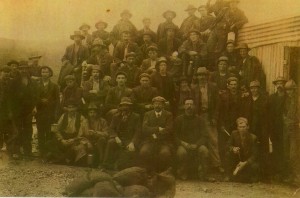

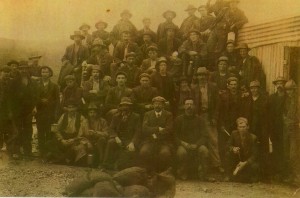

On 7 November 1909 TB Moore wrote in his diary: ‘Went into Balfour… Afternoon saw Harrisson & Insp Harrison, Langford, Speedy, young Dunne. The above with the two Murrays had our photos taken in a group. Fine & warm.’ Moore is at the extreme left in the back row. Beside him are William and Tom Murray. Courtesy of Michael Simco.

By the spring of 1909, investors were agog at the 1100 tons of ore, averaging about 30% copper, which the Murrays had reportedly dispatched. In addition, three or four times as much high grade ore was said to have been ‘at grass’ on the property. In October 1909 a report circulated that the brothers had sold the Copper Reward mine for £50,000 and an interest in a company with a big working capital—a claim the Murrays denied.[8] Meanwhile a township named after nearby Mount Balfour developed.

The workforce of the Copper Reward mine, with William Murray centre at front, and engine driver William McArthur seated to his left. Photo courtesy of Edie McArthur.

The entire mining field appears to have been invigorated by developments at the Copper Reward. Mount Lyell was stamped all over the speculation boom that followed. The Central Mount Balfour Company, with Mt Lyell Co directors Aloysius Kelly and Herman Schlapp in prominent roles, was floated in Melbourne with £25,000 subscribed capital. The adjoining Balfour Blocks Company had Mount Lyell supremo Bowes Kelly as chairman of directors. Meanwhile, veteran prospector and explorer Thomas Bather (TB) Moore dug away at the Norfolk Ranges at the behest of his boss, Robert Sticht.[9] In May 1910 the first sod was turned on the Stanley to Balfour Railway, a farcical grab at timber and hydro-electric power concessions by the Melbourne promoters of the Mount Balfour Copper Mines NL, now styling themselves the Mount Balfour Mining and Railway Company—mimicking the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company.[10]

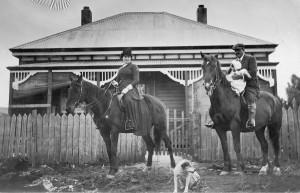

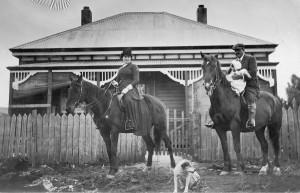

Hazel and William Murray in front of their ‘mansion’ at Balfour, 1911, with daughter Jean. Marital bliss or a façade for the photographer? Photo 1997:P:5591, QVMAG, Launceston.

It must have been tempting for the Murray brothers to start living the good life that the speculation promised, and which could easily have landed them in debt. Forty-eight-year-old William took an eighteen-year-old wife, Melbourne-born Hazel, née Myers (1891–1973).[11] Married in Sydney, the couple honeymooned first at Jenolan Caves, then in England while their Balfour home was built.[12] The Circular Head Chronicle noted that the house, with its concrete double chimneys, would provide ‘a magnificent contrast to our present canvas and paling humpies, to say nothing of those described by a recent visitors as being made of opened out sardine tins’.[13] TB Moore referred to the Murrays’ house as ‘the mansion’.[14] It is possible that Hazel Murray wasn’t quite so impressed with it when, in mid-1911, following on from their antipodean jaunt, William brought his young bride, baby and maid to Balfour via stage coach and the new horse-drawn tramway from Temma.[15] How happy the couple seems in the photo, with Hazel astride her horse, and William clutching their first daughter, Jean Wallace Murray.[16] Did Hazel adjust to frontier living, or did she ‘fly’ back to ‘civilisation’?

The fate of the Murray brothers is a staple of Tasmanian mining folklore, even being the subject of a play.[17] William Murray shot himself in his home at Donald Street, Balfour, in November 1912, reputedly as part of an unfulfilled double suicide pact with his brother Tom.[18] William was a quiet and private man: only he would know why he suicided. In her description of William and Hazel Murray’s wedding, the social writer for the Star newspaper referred to the brothers by their second names, Wallace and Charles: perhaps they had new social pretensions in Sydney. Had the Murrays missed their big chance to sell the mine, had dreams of marriage and riches crashed? It has been claimed that they refused an offer of £30,000 for a mine that ultimately proved a failure.[19] However, it had not failed at the time of William Murray’s death, and the copper price was starting to recover from the 1907 crash. It was sadly appropriate that William’s death was overshadowed by the tragedy of the North Mount Lyell fire, which killed 42 miners.[20]

William Murray bequeathed Hazel his life insurance policy to the value of £250—providing death by suicide was covered. She would not have been able to claim on an accident policy to the same value. She also received half the value of his mining interests, the other half being divided between his brother Tom Murray and others.[21] Perhaps debts absorbed all this and more. In 1913, 22-year-old mother-of-two Hazel was operating a boarding house at Battery Point, Hobart, but later she appears to have returned to her family.[22] Little is known about her life in Sydney. Her second daughter, Mary Fullarton Murray, married in 1937, but the other, Jean, had an unhappy love affair, suing her lover for £1000 in 1942 for breach of marriage contract.[23]

Tom Murray reputedly suffered a mental breakdown after his brother’s suicide, although he was apparently fit enough to walk from Hobart to Balfour to tend William’s grave.[24] Certainly he seems to have led a listless life, returning to Balfour in 1916 and 1920, then selling up his farm at Forest in 1924 with the intention of leaving the state.[25] Tom hunted osmiridium at Adamsfield two years later.[26] Described as having ‘no occupation’ and being ‘late of Roger River’, he died intestate at Latrobe in 1938, aged 75.[27] The Copper Reward mine remains untested at depth.

[1] ‘The Late Rev WWF Murray, MA’, Church News, October 1894, p.156; Whitfield Index (LINC Tasmania, Launceston)

[2] The Tasmanian Pioneers Index records that William Wallace Fullarton Murray senior and Louisa Augusta Schaw married at Richmond, Tasmania, in 1851 and produced five children at New Norfolk, Louisa Augusta Murray (born 1854), Mary Wallace Murray (born 1857), Eleanor Carter Murray (born 1859), then the two boys. William Wallace Fullarton Murray junior’s birth, recorded without given names, was 23 April 1861 (RGD33, 1664/1861). Thomas Charles Murray was born 5 October 1862 (RGD33, 1188/1862). However, the author of ‘The Late Rev WWF Murray, MA’, Church News, October 1894, p.156, records that he was survived by six girls, two of them married, and two unmarried sons.

[3] Valentia Kate (Kate Valencia) Murray (died 1948) married William Wilbraham Ford at Hobart in 1897, registration no.270/1897. For Ford as Smith’s grub-staker, see ‘A Balfour mining case: decision reserved’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 August 1910, p.2.

[4] For WW Ford as promoter, see ‘Mt Balfour Copper Mines’, Circular Head Chronicle, 15 April 1908, p.2, in which Ford invites the newspaper’s reporter to the mining field as a guest of the Murray brothers.

[5] ‘A Balfour mining case: decision reserved’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 August 1910, p.2. For William and Tom Murray’s gold leases, see Queenstown Assessment Roll for 1908, Tasmanian Government Gazette, 15 October 1907, p.1504. Tom Murray was then the owner/occupier of a cottage in Peters Street, Queenstown (p.1497). The Tasmanian Post Office Directory for 1907 (p.437) and 1908 (p.439) lists both Murrays as ‘mine owner, Queenstown’, whereas the 1909 edition (p.417) has them both as ‘mine owner, Mt Balfour’.

[6] ‘A Balfour mining case: decision reserved’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 August 1910, p.2. In 1910 the Court of Mines adjudicated that Smith’s one-fifth share now belonged to Ernest Plummer and James Loftus Wells of Stanley (a one-tenth share each), to each of whom Smith had sold half his interest before he disappeared (‘Murray’s [sic] Reward Mine: Balfour mining action’, Circular Head Chronicle, 31 August 1910, p.2). A Murray brothers appeal to the Supreme Court in 1911 overturned this decision, denying Plummer and Wells any interest in the Murrays’ Copper Reward mine (‘A mining dispute: the Murray Reward claim: judgment for defendants’, Circular Head Chronicle, 3 May 1911, p.2).

[7] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 13 July 1910, p.3.

[8] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 26 October, p.3; and 4 November 1911, p.2.

[9] See TB Moore diaries for 1908 and 1909, ZM5640 (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery [hereafter TMAG]).

[10] ‘The Balfour Railway: turning the first sod’, Circular Head Chronicle, 10 May 1910, p.2.

[11] ‘Personal’, Circular Head Chronicle, 19 January 1910, p.2.

[12] ‘Social news’, Star (Sydney), 29 January 1910, p.16.

[13] ‘Mount Balfour’, Circular Head Chronicle, 9 February 1910, p.3.

[14] TB Moore diaries, 30 April 1912, ZM5641 (TMAG).

[15] ‘Balfour: general news’, Circular Head Chronicle, 30 August 1911, p.2.

[16] Did the maid hand the baby over to her father so that she could take the photo?

[17] The play is Heather Nimmo’s ‘Murrays’ Reward: a play in two acts’.

[18] The Circular Head Chronicle (‘Deaths at Balfour’, 6 November 1912, p.2) reported merely that Murray had ‘died suddenly’. The coroner found that Murray died of a self-inflicted ‘gunshot wound to the head … while of unsound mind’ (see SC195-1-82-13112, [TAHO]).

[19] E Payne, ‘Balfour mine’, Examiner, 19 March 1951, p.2.

[20] ‘Deaths at Balfour’, Mercury, 7 November 1912, p.4; death notice, Mercury, 20 November 1912, p.1.

[21] Will no.9043, AD960-1-34 (TAHO).

[22] The Hobart Assessment Roll for 1913 places her as a tenant in De Witt Street, Battery Point (Tasmanian Government Gazette, 8 December 1913, p.2426).

[23] ‘Out of town news’, Sydney Morning Herald, 9 March 1937, p.3; ‘Woman to receive £1000 damages’, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 September 1942, p.7.

[24] For Tom’s reputed mental breakdown see, for example, Kerry Pink and Annette Ebdon, Beyond the ramparts: a bicentennial history of Circular Head, Tasmania, Circular Head Bicentennial History Group, Smithton, 1988, p.249. For Tom’s return visits to tend William’s grave, see Joan Foss, Memories of the Marrawah Sand Track (held by Circular Head Heritage Centre, Smithton). Tom Murray reportedly asked to be relieved of the management of the Copper Reward in 1913 because of ill health (‘The Balfour field’, Circular Head Chronicle, 17 December 1913, p.2).

[25] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 13 June 1916, p.3; ‘Personal’, Circular Head Chronicle, 30 June 1920, p.3; advert, Advocate, 3 May 1924, p.8.

[26] ‘Forest’, Circular Head Chronicle, 14 July 1926, p.5.

[27] ‘Deaths’, Mercury, 16 August 1938, p.1. Probate was valued at only £168, see AD963-1-3-2352 (TAHO). He was buried at Cornelian Bay Cemetery, Hobart. An Examiner correspondent later claimed that Tom Murray ‘just sold me the machinery and left’, predicting that ‘we have not heard the last of Balfour yet’ (E Payne, ‘Balfour mine’, Examiner, 19 March 1951, p.2).