Death of the Devonport Gold Mine huts, or memories of gold fever and Chunder Loo

The old vehicular track up the Black Bluff Range at Smiths Plain in north-western Tasmania is scoured down to the bedrock. In places the holes are so deep and slippery that it’s difficult to clamber up; in other places you are buffeted by the scrub over-reaching from both sides. The object of the climb, the Devonport Gold Mine, has lain idle for decades, but even though the road is now impassable for vehicles you can’t help but be impressed by the enterprise of the miners in establishing it.

In making this climb on foot several years ago, I was reminded of Ron Smith’s account of the same journey more than a century earlier. Nowadays you drive to Smiths Plain and walk from there along forestry roads to the base of the bluff. Twenty-six-year-old Smith had no car. Early one morning in December 1907 he set out for Black Bluff from his home at Westwood, near Forth. A fourteen-kilogram swag was balanced on the front of his bicycle, camera (two kg) and field glasses were slung over his shoulders. Four hours after leaving home he decided to eat lunch—at 9.16 am, for all of six minutes!—near Blackwood Park at Nietta. Leaving his bicycle at a point two miles beyond Phillips’ house at South Nietta, and taking a second bite of lunch at 11.45 am, he started across the then mostly button-grass Smiths Plain.[1]

The plain took its name from it being his father’s point of entry to the high country. Prospector James ‘Philosopher’ Smith’s route over the Black Bluff Range and down to the Lea River had been his access to discoveries of gold, copper and manganese he had made in the area. Other prospectors had followed in his footsteps. One was Alf Smith, an unrelated prospector who, like others, had worked on Philosopher Smith’s farm through the winters as part of the latter’s scheme to support mineral prospecting.[2] Panning his way up Devonport Creek in 1902, Alf and his brother-in-law Reuben Richards found what they thought was a gold reef.[3] Alf worked this mine and one at Copper Creek, Lea River, building tiny huts at both sites.

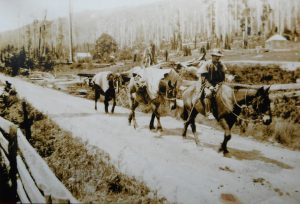

No knapsacks? Alf Smith (left) and fellow miners preparing to climb the Black Bluff Range, 22 October 1909. All of them seem ill equipped for the long haul up and over the mountain. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The foot track of a century ago climbed a spur of Mount Jacob through eucalypt forest, affording views of the Shepherd and Murphy Tin, Tungsten and Bismuth Mine and the All Nations Tin and Tungsten Mine near Moina. Like the present-day Devonport Gold Mine vehicular track, the foot track avoided the gorge formed by a creek running eastward from Tiger Plain towards the Iris River. Today the vehicular track has spread out like a delta on both sides of the creek, suggesting that over the years people have chosen different crossing points. One day I met a bearded old man coming down the hill to the stream crossing. His flowing hair and team of dogs made me wonder if he was the ghost of Philosopher Smith returning from a prospecting expedition.

Philosopher’s son took the staked track which crossed the range to the Lea River. As it began to descend from its exposed highest point Smith diverted from it to the east, endeavouring to find the track to the Devonport Prospecting Association (DPA) Gold Mine, as it was then known. This is the opposite of today, when you take the right-hand fork, confirming that the vehicular track did not follow the line of the earlier walking track up the hill. The walking track went further to the west, closer to the edge of Golden Cliff Gorge, the great north-south rift through the Black Bluff Range caused by a fault line.

At last Smith found the fallen stakes denoting the DPA track. He reached Alf Smith’s hut at 4.25 pm, after a journey of more than nine hours from Forth. The hut, Smith wrote, was built of red (pencil) pine, there being a small stand of it nearby. It had

‘a fireplace at the east end, and a verandah on the north side, under which the door opened. Two bunks (single), one above the other, took up the west end and a double bunk half the north side … A window, one large sash, was in the south side’.[4]

The hut was well furnished, with table, stools and even cooking and eating utensils. Next day Smith visited the trig station on Black Bluff, travelling mostly by compass through the mist, and photographed the DPA adit and the blacksmith’s shop near it.[5]

It was a poor gold mine. Early assays approached a very respectable ounce per ton, but this was due to the sampling of surface enrichment that could not be expected to continue at depth. Examining both the irregular quartz vein cut in the adit and the gossan accessed in trenches, in 1913 Government Geologist William Harper (WH) Twelvetrees predicted only ‘negligible quantities of gold’ at depth, with the ore changing to iron sulphide.[6] Subsequent geological reports and returns confirmed this, but the allure of gold kept men coming.[7]

Alf Smith’s hut at the Devonport Prospecting Association (DPA) Mine, 1907.

Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Depreciation of the British pound in 1931 gave the gold price a boost. In a repeat of the 1890s depression, diggers retried old gold shows, hoping to plunder a supposed reef that had failed to yield its treasure last time. Hunting also drove men into the bush, with 1934 being a record season for ringtails. Cliff Beswick and Reg Ling were reworking Black’s Lea River Gold Mine when Bernard ‘Barney’ Fry walked off a nearby cliff while out possuming by acetylene light.[8] Cashman’s Gold Mining Syndicate sank new shafts and extended one of the adits in search of the Lea River lode in 1940.[9]

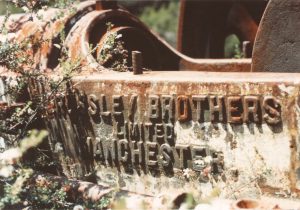

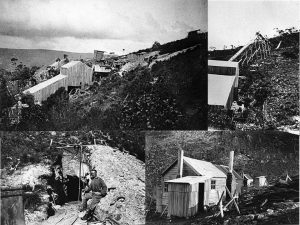

(Clockwise from top left) Probably 1950s photos of the gravity-fed mill; the trolley way from the adit to the mill; the entrance to the adit; and the huts, Devonport Gold Mine. Colin Dennison Collection, University of Tasmania Archives.

The final abandonment of the mine left infrastructure to crumble high on the exposed spine of Black Bluff. Historian Dr Peter Bell’s examination of the overgrown, plundered site in 1995 revealed a technological morass, including a 1923 Crossley oil engine that was set up to power a treatment plant on the opposite side of Devonport Creek, a Forwood Down grinding pan, a 1920s–30s Lister oil engine, a steam winding engine and a late-nineteenth-century Cameron steam pump. The purpose of some of the gear was by then unfathomable.[12]

Devonport Mine hut from the rear, looking towards Stormont and the Lea River valley. Nic Haygarth photo.

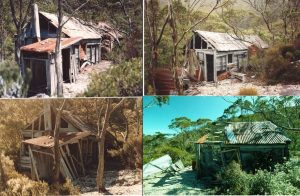

The remains of what was probably the blacksmith’s shop; and the adventures of Chunder Loo, Devonport Gold Mine, 1995. Nic Haygarth photos.

The two-room hut still stood, although the broken windows were covered up and the exterior boards appear to have been torn off and used for firewood, exposing the wall cavities to the elements. There was no recovery from here without urgent attention. Inside the hut you could read the wallpaper—pages of Sydney magazine the Bulletin from 1915! (One of the pages featured ‘Chunder takes a trip home’, satirical verses by Ernest O’Ferrall, whose Sri Lankan character Chunder Loo originally appeared in newspaper advertisements for Cobra boot polish. O’Ferrall’s Adventures of Chunder Loo, illustrated by Lionel Lindsay, was later issued as a book, with verses appearing in the Bulletin.)[13] This aged wallpaper suggested that part of the hut, at least, dated from the first operation of the mine, possibly even incorporating elements of Alf Smith’s pencil pine hut.

The vehicular track enabled the Crossley to be removed from the mine, reducing the site’s integrity but allowing restoration of the now rare engine at Pearn’s Steam World, Westbury. Since the exterior walls were removed, the two-room hut has declined rapidly, such that within a few years there will be no standing walls at the Devonport Mine. Rarely was gold fever more virulent than here, defying geological argument for most of a century.

[1] Ron Smith diary, 13 December 1907, NS234/16/1/4 (TAHO).

[2] Nic Haygarth, Baron Bischoff: Philosopher Smith and the birth of Tasmanian mining, the author, Perth, Tas, 2004, p.136.

[3] ‘A Barren Bluff find’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 19 February 1902, p.3.

[4] Ron Smith diary, 13 December 1907.

[5] Ron Smith diary, 14 December 1907.

[6] ‘Middlesex district’, North West Post, 5 March 1914, p.4.

[7] See, for example, QJ Henderson, ‘Departmental report on the Devonport Mine, Black Bluff’, Unpublished reports, 1939, pp.61–64.

[8] ‘In darkness: stumbled over cliff: hunter’s death’, Examiner, 5 June 1934, p.7.

[9] ‘Gold at Black Bluff’, Examiner, 13 March 1940, p.4.

[10] ‘Gold at Black Bluff’, Advocate, 9 March 1942, p.4.

[11] Peter Bell, Devonport Mine near Black Bluff: report to Tasmania Development and Resources, Archaeological Survey Report 1995/03, Historical Research Pty Ltd, Adelaide, 1995, p.2.

[12] Peter Bell, Devonport Mine near Black Bluff, pp.1–4, 17–18, 24–26.

[13] Douglas Stewart Fine Books website, https://douglasstewart.com.au/product/adventures-chunder-loo/, accessed 14 December 2018.

Basil and Cutter Murray: tigers and other travelling tales

Arthur ‘Cutter’ Murray reckoned that thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) followed him when he walked from Magnet to Waratah in the state’s far north-west—out of curiosity, rather than malicious intent. If he swung around suddenly he could catch a glimpse of one.[1] However, Cutter did better than that. In 1925 he caught a tiger alive and took it for a train ride to Hobart.

Tigers are just one element of the twentieth-century tale of Cutter and his elder brother Basil Murray. Yet for all their exploits these great high country bushmen started in poverty and rarely glimpsed anything better. Cutter married and produced a family, but his weakness all his working life was gambling: what he made on the possums (and tiger) he lost on the horses. Basil made enough money to keep the taxman guessing but was content to live out his days in a caravan behind Waratah’s Bischoff Hotel.[2]

Their ancestry was Irish Roman Catholic. Basil Francis Murray (1893–1971) was born to Emu Bay Railway ganger Edward James (Ted) Murray and Martha Anne Sutton. He was the couple’s ninth child. Arthur Royden Murray (1898–1987?) was the twelfth.[3] Three more kids followed. The family lived at the fettlers’ cottages at the Fourteen Mile south of Ridgley while Ted Murray was a ganger, but in 1907 he became a bush farmer at Guildford, renting land from the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co).[4] Guildford, the junction of the main Emu Bay Railway line to Zeehan and the branch line to Waratah, had a station, licensed bar and state school, but was also a centre for railway workers, VDL Co timber cutters and hunters. Edward Brown, the so-called ‘Squire of Guildford’, dominated local activity.

Guildford Junction State School, with teacher May Wells at centre. From the Weekly Courier, 10 November 1906, p.24.

Squaring sleepers, splitting timber, hunting, fencing, scrubbing out bush, driving bullocks, herding stock, milking cows and setting snares were essential skills for a young man in this locality. Like others, the Murrays snared adjoining VDL Co land, paying the company a royalty. Several Murray boys escaped Guildford by serving in World War One, but Cutter recalled that his father would not let him enlist.[5] Basil also stayed home.[6] Perhaps it was enough for Ted and Martha Murray that they lost one son, Albert Murray, killed in action in France in 1916.[7]

Guildford Railway Station during the ‘great snow’, 1921. Winter photo, Weekly Courier, 18 August 1921, p.17.

Guildford Station under snow again, 24 September 1930. RE Smith photo, courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Twenty-three-year-old Arthur Murray appears to have married Alice Randall in Waratah during the ‘great snow’ of August 1921. He would already have been a proficient bushman. Cutter learned to use the treadle snare with a springer, although he would also employ a pole snare for brush possum and would shoot ringtails. He shot at night using acetylene light to illuminate the nocturnal ringtails, but he found it easier to go after them by day by poking their nests in the tea-tree scrub. ‘It was like shooting fish in a barrel’, Cutter’s son Barry Murray recalled. ‘It was only shooting as high as the ceiling … A little spar and you just shook it … and they’d come out, generally two, a male and a female …’[8] Hunters aimed for the nose so as to keep the valuable fur untainted.

In the bush Cutter lived so roughly that no one would work with him. Some tried, but none of them lasted. His huts and skin sheds on the Surrey Hills were little more than a few slabs of bark. Friday was bath day, which meant a walk in Williams Creek (east of the old Waratah Cemetery), regardless of weather conditions. Cutter’s son Val once snared Knole Plain with him, but couldn’t keep up. Snares had to be inspected every day, the game removed, and the snares reset. Cutter and Val took snaring runs on opposite sides of the plain, but Val found that even if he ran the whole way and didn’t reset any snares, Cutter would be sitting waiting for him, having long completed his side.

Cutter’s most substantial skin shed was near home base, on the hill above the primary school at Waratah. Here he would smoke the skins before an open fire. He pegged them out both on the wall and on planks about eighteen inches wide, each plank long enough to accommodate three wallaby skins. When the sun shone, he took the laden planks outside; otherwise he sat inside the skin shed with his skins, chain smoking cigarettes in empathy. A skin shed had no chimney, the idea being that the smoke would brown the skins as it escaped through the cracks between the planks of the walls. The air was so black with smoke that Cutter was virtually invisible from the doorway.[9] Yet no carcinogens prevented him reaching his eighties.

Joe Fagan claimed that Basil Murray was such a good snarer that he once snared Bass Strait.[10] Basil preferred the simple necker snare to the treadle, and caught a tiger in such a device on Murrays Plain, a little plain above the 40 Mile mark on the railway named after Ted Murray.[11] Cutter caught a couple of three-quarters-grown tigers. One was taken dead in a treadle snare with a springer on Goderich Plain when Cutter was hunting with Joe Fagan.[12] Joe kept the skin for years as a rug, but when it grew moth-eaten he tossed it on the fire—oblivious to its rarity or future value.[13] Cutter caught the other thylacine alive in a treadle near Parrawe.[14] He trussed her up and humped her home, where ‘a terrific number of people’ came for a look.[15] ‘They’re very shy animals really, and quite timid’, he recalled of the captive female. ‘It behaved just like a dog and it got very friendly. But when a stranger came near it would squark at them.’[16] At first he couldn’t get her to eat. The breakthrough came when he skinned a freshly caught wallaby, rolled the carcase up in the skin with the fur on the inside, and fed it to the tiger while it was still warm.[17] In June 1925 ‘Murray bros, Waratah’ advertised a ‘Tasmanian Tiger (female)’ in the ‘For sale’ columns of the Examiner and Mercury newspapers.[18] Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo offered £30 for it, prompting Cutter to deliver her by train. It was his only visit to Hobart. Four cruisers of the American fleet were in town, and Cutter recalled that ‘it was so crowded you could hardly move. I didn’t like it much’.[19]

The other big event in Hobart at the time was the Adamsfield osmiridium rush, which ensnared Basil Murray. In the last quarter of 1925 he pocketed £126 from osmiridium, the equivalent of a year’s wage for a farmhand.[20] Later he spent six months mining a tin show alone at the Interview River. Having set the exact date he wanted to be picked up by boat at the Pieman River heads, Basil hauled out a ton of tin ore on his back, bit by bit.[21] On another occasion he worked a little gold show on the Heazlewood River, curling the bark of gum saplings to make a flume in order to bring water to the site.[22]

It was pulpwood cutting that gave Arthur Murray his nickname. When Associated Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) started manufacturing paper at Burnie in 1938, it turned to Jack and Bern Fidler of Burnie company Forest Supplies Pty Ltd for pulpwood.[23] Over the next two decades Joe Fagan supplied about one-third of the pulpwood quota as a sub-contractor to the Fidlers. At a time when Mount Bischoff was a marginal provider for a few families, and osmiridium mining had fizzled out, Fagan became a significant employer, with about 65 men splitting barking and carting cordwood to the railway at Guildford for transport to Burnie.[24]

A good splitter would split about 3 cords of wood (a cord equals 128 cubic feet of timber) per day. Cutter held the record for the best daily effort, 8½ cords. Unlike most splitters, he never used an axe, but wedged off and split the billet into three pieces. Yet Cutter’s pulpwood stacking exasperated Joe Fagan. Unlike other men, Cutter did not stack his pulpwood as he went. Pulpwood cutters were paid according to the size of their stacks, and the large gaps in Cutter’s hasty, last-minute efforts ensured that he got paid for a bit more fresh air than he was entitled to. Kicking one such stack, Joe growled:

‘I don’t mind the rabbits goin’ through, Arthur, but I bloody well hate those bloody greyhounds behind them goin’ through the holes’.[25]

World War Two was a lucrative time for snarers. £15,000-worth of skins were auctioned at the Guildford Railway Station in 1943, while more than 32,000 skins were offered there in the following year. Record prices were paid at what was probably the last annual Guildford sale in 1946.[26] Taking advantage of high demand, the VDL Co dispensed with the royalty payment system and made the letting of runs its sole hunting revenue. One party of three hunters was reported to have presented about three tons of prime skins as its seasonal haul.[27]

Both Murrays cashed in. Cutter made £600 one season.[28] Working with Eric Saddington at the Racecourse, Surrey Hills, Basil took 3000 wallabies in 1943. Unfortunately their wallaby snares also landed 42 out-of-season brush possums (21 grey and 21 black)—which landed the pair in court on unlawful possession charges. Both men were fined.[29] Basil had a reputation for being a ‘poacher’, and one story of his cunning, apocryphal or not, rivals those told about fellow poacher Bert Nichols.[30]

According to Ted Crisp, Basil was sitting at the bar at the Guildford Junction Railway Station when two Fauna Board rangers came in on the train and announced they were looking for Basil Murray, whom they believed had a stash of out-of-season skins. Then they set off for his hut, rejoining the train to go further down the line:

‘Old Baz headed down by foot and took after them, he was a pretty good mover in the bush and the trains weren’t real fast … and by the time he got down there, they’d found his skins, decided there were too many to carry out so they’d hide them and pick them up at a later date, and of course old Baz was sitting there watching them, they had to catch the train back a couple of hours later, they left and old Baz picked up the skins and moved them to another place …’

By the time the Fauna Board rangers got back to Guildford, Basil was still in the bar, propped up against the counter.[31] However, the taxman did better than the Fauna Board rangers. Basil seems to have been a chronic tax avoider. He and Eric Saddington were camped at Bulgobac, squaring sleepers and snaring, when they were busted for not filing tax returns for the years 1941–42–43.[32]

Basil kept on in the same vein, landing a £25 fine for not lodging a 1943–44 return and then a whopping £60 for the 1947–48–49 period.[33] Things finally got too hot for Basil, who adjourned to the Victorian goldfields for a time.[34]

In 1951 Basil was the cook for the party re-establishing the track between Corinna and Zeehan. One of the track-makers, Basil’s nephew Barry Murray remembered him as ‘a good old cook, as clean as Cutter was rough. They were just opposites. He had a big Huon pine table. He used to scrub it with sandsoap every day, and he would have worn it away if he’d stopped there for two or three years’.[35] Basil became well known as APPM’s gatekeeper at the Hampshire Hills.

In 1963 Cutter Murray was one of Joe Fagan’s men recruited by Harry Fraser of Aberfoyle in a party which investigated the old Cleveland tin and tungsten mine and recut the Yellowband Plain track to Mount Lindsay. At the party’s Mount Lindsay camp Cutter used snares to reduce the numbers of marauding devils that were tearing through the canvas tents, biting the tops off sauce bottles and biting open tins of beef and jam.[36]

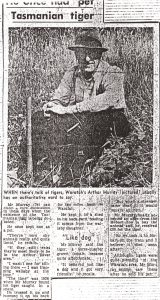

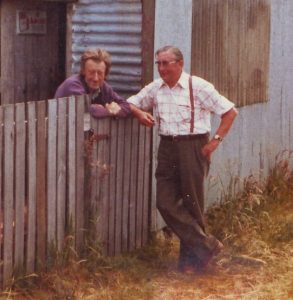

Cutter Murray (left) and friend at Waratah. Note the Ascot cigarettes advertisement on the wall behind him. Photo courtesy of Young Joe Fagan.

Cutter snared until virtually the day he died in the 1980s, making him—along with Basil Steers—one of the last of the snarers. He possumed on North’s block and took wallabies on the Don Hill, under Mount Bischoff, wheeling the skins home draped over a bicycle. A great snaring dog, a labrador that he had trained to corner but not kill escaped game, made his life easier.[37] Nothing is known to remain of his hunting regime, not a hut or a skin shed. Barely a photo remains of the hardy bushman. His tiger tale flitted across the country via newspaper in 1984, then was forgotten.

Unfortunately Cutter Murray’s travelling tiger has an equally obscure legacy, apparently dying soon after it was received at the Beaumaris Zoo.[38]

[1] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[2] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[3] Registration no.484, born 16 May 1898, RGD33/1/85 (TAHO). Basil Murray’s years of birth and dirt are recorded on his headstone in the Wivenhoe General Cemetery, Burnie.

[4] ‘Ridgley’, North West Post, 8 October 1907, p.2.

[5] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’, Australian, 1984, publication details unknown.

[6] Basil and John Murray were refused an exemption (‘Waratah Exemption Court’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 November 1916, p.2; ‘Burnie: in freedom’s cause’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 13 January 1916, p.2), but there is no record of Basil serving.

[7] ‘Tasmanian casualties’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 22 September 1916, p.3.

[8] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[9] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[10] Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[11] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[12] Cutter Murray and Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[13] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, the author, Somerset, 1994, pp.62–66.

[14] Cutter Murray and Joe Fagan to Bob Brown and Ern Malley, 1972 (QVMAG).

[15] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’, Australian, 1984, publication details unknown.

[16] Cutter Murray; quoted in ‘He once had pet Tasmanian tiger’, Mercury, 13 February 1973.

[17] AAC (Bert) Mason, No two the same: an autobiographical social and mining history 1914–1992 on the life and times of a mining engineer, Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Hawthorn, Vic, 1994, p.571.

[18] See, for example, ‘For sale’, Examiner, 17 Jun 1925, p.8.

[19] Cutter Murray; quoted by Mary McNamara, ‘Have Tasmanian tiger, will travel … but only once’.

[20] Register of osmiridium buyers’ return of purchases, MIN150/1/1 (TAHO).

[21] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[22] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[23] Steve Scott, quoted by Tess Lawrence, A whitebait and a bloody scone: an anecdotal history of APPM, Jezebel Press, Melbourne, 1986, p.25.

[24] Kerry Pink, ‘His heart belongs to Waratah … Joe Fagan’, Advocate, 10 August 1985, p.6.

[25] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 21 November 2008.

[26] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4; ‘Over 32,000 skins offered at sale’, Advocate, 13 September 1944, p.5; ‘Record prices at Guildford skin sale’, Advocate, 30 July 1946, p.6.

[27] ‘£15,000 skin sale at Guildford’, Examiner, 14 October 1943, p.4.

[28] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[29] ‘Trappers fined’, Advocate, 22 October 1943, p.4.

[30] For Nichols’ poaching, see Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.116–19.

[31] Ted Crisp; quoted by Tess Lawrence, A whitebait and a bloody scone: an anecdotal history of APPM, p.26.

[32] ‘Men fined’, Mercury, 5 May 1944, p.6.

[33] ‘Fines imposed for income tax offences’, Mercury, 5 September 1946, p.10; ‘Fined for tax breaches’, Examiner, 6 July 1950, p.3.

[34] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[35] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[36] AAC (Bert) Mason, No two the same, pp.570–71, 577, 579.

[37] Barry Murray, interviewed by Nic Haygarth, 23 July 2011.

[38] Email from Dr Stephen Sleightholme 26 December 2018; Cutter Murray stated his belief that it died soon after arrival in Hobart in ‘He once had pet Tasmanian tiger’. I thank Stephen Sleightholme and Gareth Linnard for their contributions to this story.

Checklist of the 250 osmiridium diggers in 1922

Osmiridium diggers meeting their wives and receiving their stores at the Nineteen Mile Hut, probably in 1921. JH Robinson photo from the Colin Dennison Collection, University of Tasmania Archives.

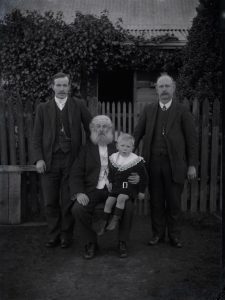

Four generations of Waratah’s Thorne family, including osmiridium miner and buyer JH Thorne at right. JH Robinson photo courtesy of the late Nancy Gillard.

The diggers were grizzling. In 1921 Tasmania enjoyed a world monopoly on ‘point metal’ osmiridium, that is, osmiridium grains that were just the right size to fuse onto the nibs of gold fountain pens. The ossie price was generally high. Tasmania’s niche in the market was unchallenged. The diggers on the fields west and south-west of Waratah should have been happy.

They weren’t. Part of the problem was that few had a grasp of economics. They did not understand that they dampened demand by rushing their ore to market. Remotely located diggers working alone felt cut off from the metal market. Some were convinced that they were the victims of collusion between precious metal buyers who were determined to force down the price.

Secretary of the osmiridium pool, Chris Sheedy, is third from left at back. Second from left in the front row is Chris Sheedy senior, onetime foreman of the Brown Face at the Bischoff mine. Photo courtesy of John Turnbull.

Calls for government to intervene in the market were finally answered when Premier Sir Walter Lee agreed to introduce an experimental monopoly. As of 1 January 1922, precious metals dealer Overell & Sampson held the only Tasmanian osmiridium buyer’s licence—so now there could be no collusion. Could the company get the diggers a better price for their metal? Almost 250 men banked on it, selling their osmiridium through the government scheme. The list of sellers compiled on 30 June 1922 is now a handy checklist for historians and genealogists. Here are the men in one long list by rough alphabetical order as set out in the government records.[1] My only addition is some comments in the column at right.

| Name | Value of os (£, s & d) | Weight of os (oz, dwts & grains) | Comments |

| Anderson, Thomas | 35-15-7 | 2-3-9 | |

| Aylett, George | 40-11-3 | 2-7-5 | |

| Aylett, William | 85-9-8 | 5-0-12 | Later at Adamsfield |

| Allan, G & W | 97-10-7 | 5-10-1 | |

| Allan, BJ | 40-10-0 | 2-0-12 | |

| Allan, J | 40-0-0 | 2-0-0 | Jim Allan, Nineteen Mile Creek |

| Baptist, J | 50-0-0 | 3-14-21 | John D’Ahren Baptiste, aka Hooky Jack, later at Adamsfield. |

| Baptist, J (Reserve) | 100-5-0 | 5-0-6 | |

| Beale, W | 30-6-6 | 1-14-8 | |

| Berryman, E | 133-7-10 | 8-18-17 | |

| Berkery, M | 27-18-7 | 1-12-0 | |

| Buckingham, H | 11-3-3 | 0-11-20 | |

| Betts, WA | 46-14-4 | 3-1-23 | Betts Track named after a Betts prospector. |

| Biggins, Norman | 26-5-0 | 1-15-0 | |

| Billinghurst, J | 20-11-0 | 1-3-16 | |

| Booth, George | 31-18-9 | 2-2-14 | |

| Booth, William | 45-2-5 | 2-17-4 | |

| Boyd, H | 53-6-0 | 3-5-11 | |

| Brown, G | 20-0-0 | 1-19-21 | |

| Bryant, JH | 71-8-9 | 4-13-14 | Former Derby shopkeeper. Committee member of the osmiridium pool. |

| Burness, J | 16-15-0 | 1-2-8 | |

| Burness, Charles | 18-5-0 | 1-4-8 | |

| Brettoner, JE | 18-5-0 | 1-4-8 | |

| Blake, UJ | 12-12-3 | 0-16-3 | |

| Bosich, L | 13-15-0 | 0-18-8 | |

| Brodie, W | 1-11-8 | 0-1-14 | |

| Button, A | 47-19-5 | 2-9-18 | |

| Booth, George Jnr | 32-9-2 | 1-12-11 | |

| Burge, J | 11-14-2 | 0-11-17 | |

| Burke, RH | 2-11-0 | 0-3-0 | |

| Bynon, R | 42-11-3 | 2-5-17 | |

| Blair, F | 8-0-0 | 0-8-0 | |

| Burness, HB | 21-5-0 | — | |

| Callaghan, B | 75-13-6 | 4-10-12 | |

| Carpenter, T | 53-18-4 | 3-6-18 | |

| Carmody, H | 37-0-0 | 4-0-0 | |

| Clementson, M | 13-3-5 | 1-3-15 | Matty Clementson, ‘the [Mount] Stewart king’. |

| Coghlan, J | 17-0-0 | 0-17-0 | |

| Crawford, T | 53-0-7 | 5-10-5 | |

| Casey, W | 75-0-7 | 4-0-13 | |

| Casey, W | 43-14-11 | 2-18-8 | |

| Cashman, John | 39-18-2 | 2-9-15 | |

| Caudry, William | 15-0-0 | 1-0-0 | Caudry’s Reward reef mine, Caudrys Hill, the first mine of its kind in the world. Also had a lease at Mount Stewart. |

| Caudry, William | 100-0-0 | 5-0-0 | |

| Caudry, Thomas | 62-17-6 | 3-2-21 | Brother of William Caudry. |

| Cooney, J | 45-17-6 | 2-5-21 | |

| Cumming, R | 47-19-7 | 2-9-18 | |

| Chellis, WH | 128-11-8 | 6-8-14 | Walter Chellis, Castray River, champion axeman & publican. |

| Cook, Henry | 48-13-10 | 2-18-2 | |

| Cady, W | 31-7-8 | 1-16-22 | |

| Davidson, J | 19-0-7 | 1-2-3 | Jack Davidson, stalwart of the Nineteen Mile. |

| Devlyn, Fred | 73-9-6 | 4-0-3 | |

| Devereaux, H | 28-9-7 | 1-12-3 | |

| Dixon, J | 49-4-7 | 2-15-15 | |

| Doak, William | 5-18-9 | 0-7-23 | Doaks Creek at Adamsfield named after him. |

| Doran, William | 47-14-7 | 3-0-7 | |

| Donovan, D | 42-0-0 | 2-6-0 | |

| Dhu, Hugh | 47-2-4 | 2-14-20 | |

| Dunn, Steve | 34-8-6 | 2-0-12 | |

| Drew, M | 21-11-7 | 1-5-16 | |

| Duffy, James & Manion, Thomas | — | 1-2-0 | |

| Devlyn, John | 6-5-7 | 0-8-9 | |

| Dixon, TF | 12-13-2 | 0-16-8 | |

| Dwyer, S | 42-11-10 | 2-13-4 | Sammy Dwyer, from NSW, last man at the Nineteen Mile, 1950s |

| Duffy, J | 27-4-2 | 1-14-23 | |

| Dunn, John | 23-13-4 | 1-3-16 | |

| Donohue, J | 18-16-0 | 1-0-6 | |

| Davies, D | 20-6-6 | 1-2-3 | |

| Dickson, C | 42-10-7 | 2-5-16 | |

| Davie, A | 48-10-0 | 2-10-0 | Probably Arthur Davey, one of the stalwarts of the Nineteen Mile. |

| Dettoner, AC | 11-12-4 | 0-11-16 | |

| Davies, C | 25-0-0 | 1-5-0 | |

| East, G | 61-16-8 | 5-5-20 | |

| Easther, C & Garrett, T | 100-4-2 | 5-0-5 | |

| Easther, C | 52-4-7 | 4-16-8 | |

| Eastwood, William | 38-16-8 | 2-13-2 | |

| Elmer, William | 57-19-1 | 4-6-9 | |

| Ellims, V | 79-19-0 | 4-11-18 | |

| Evans, Charles | 58-10-7 | 3-8-3 | ‘Chillie’ Evans, a well-known digger. |

| Eames, G | 71-10-7 | 4-0-15 | Jones Creek digger George Eames, whose dealings with osmiridium buyer Robert Krebs in 1923 helped bring down the government monopoly scheme. |

| Etchell, Thomas | 18-16-3 | 1-4-10 | Brother of well-known bushman, Luke Etchell, with whom he lived at Guildford. They were also pulp wood cutters and snarers. |

| Fenton, S | 58-18-1 | 3-6-23 | |

| Ferguson, WJ | 18-5-5 | 3-4-6 | |

| Flowers, S | 31-17-0 | 3-5-19 | |

| Forbes, A | 47-5-0 | 6-3-0 | |

| Finlay, R | 50-19-10 | 2-12-7 | |

| Fenton, AW | 43-2-6 | 2-13-13 | |

| Ferrari, S | 99-3-11 | 5-5-8 | |

| Frazer, JD | 10-8-3 | 0-11-21 | John D ‘Scotty’ Frazer, a well-known digger who disappeared in the bush in 1923, thought to have drowned. |

| Findon, John | 14-0-0 | 0-14-0 | |

| Fahey, James | 69-8-4 | 4-0-17 | |

| Farquhar, John | 27-4-8 | 1-8-8 | |

| Flight, W | 12-18-6 | 0-15-5 | |

| Finlay, JH | 1-18-4 | 0-1-22 | Jack Finlay, remembered by osmiridium fields poet Mulga Mick O’Reilly as ‘Jack Fennelly’. |

| Garratt, T | 52-4-7 | 4-16-8 | Probably Tyson Garrett of Savage River. |

| Grant, William | 19-9-1 | 1-3-6 | |

| Grant, Charles | 43-10-6 | 2-8-12 | |

| Grills, H | 51-15-8 | 3-19-4 | |

| Grosser, PA | 79-11-0 | 4-15-0 | Magnet’s Phil Grosser, of Mount Stewart and the Nineteen Mile, later at Adamsfield. |

| Grubb, John | 18-16-4 | 1-0-9 | |

| Gould, J | 21-1-2 | 1-2-17 | |

| Gatehouse, H | 79-11-8 | 3-19-14 | |

| Gurney, C | 3-3-0 | 0-3-17 | |

| Harper, Thomas | 25-8-8 | 1-9-3 | |

| Hamilton, William | 21-7-6 | 1-11-17 | |

| Harrison, J | 25-0-0 | 4-16-3 | Is this Wynyard’s James ‘Tiger Cat’ Harrison, real estate agent, ‘human cork’ and prospector, who dealt in live marsupials, including thylacines? |

| Henderson, C | 14-11-10 | 0-18-18 | |

| Hines, William J | — | 0-12-7 | |

| Hodson, H | 17-3-3 | 1-1-5 | |

| Hughes, Victor | 24-14-9 | 3-8-5 | |

| Humphries, Albert | 43-12-3 | 2-11-16 | |

| Humphries, Albert | 36-6-10 | 1-19-12 | |

| Humphries, R | 52-0-10 | 3-6-1 | Probably Magnet resident Robert Humphries, of the Mount Stewart field. |

| Hancock, J | 31-13-10 | 2-0-5 | Probably Jos Hancock, of Flea Flat, Nineteen Mile Creek, whose hut was used as a location in the movie Jewelled Nights in 1925. |

| Hanlon, T | 93-8-3 | 5-5-22 | |

| Harvey, Joseph | 72-17-7 | 4-9-0 | |

| Humphries, HH | 34-18-4 | 1-14-22 | |

| Harrison, M | 32-0-0 | 1-12-0 | |

| Hope, A | 22-1-8 | 1-2-2 | |

| Hollow, J | 43-4-2 | 2-3-5 | |

| Hill, Kenneth | 19-8-0 | 1-3-10 | |

| Inglis, AL | 33-6-8 | 1-13-8 | |

| Inglis, AL | 208-0-0 | 10-0-0 | |

| Jones, RW | 100-0-0 | 10-0-0 | Probably Robert Walter Jones, aka Wally Jones, who later went to Adamsfield and was osmiridium buyer HB Selby & Co’s agent there. |

| Jones, CH | 22-14-4 | 1-10-7 | |

| Jans, FC | 77-6-5 | 4-6-0 | Fred Jans, later at Adamsfield, where he died in 1944. |

| Johnston, L | 31-15-0 | 1-11-18 | |

| Jones, TH | 60-0-0 | 3-0-0 | Possibly Tom Jones, after whom Jones Creek was named. |

| Jones, John | 16-0-1 | 0-17-16 | |

| Jenner, H | 8-5-6 | 0-8-12 | Harry Jenner, later at Adamsfield. |

| Keltie, William | 18-3-11 | 1-2-23 | |

| Kenny, J | 57-17-6 | 4-7-9 | |

| Kinsella, A | 39-2-8 | 2-8-21 | Possibly related to Bill Kinsella of Wilson River. |

| Kelcher, John | 38-9-11 | 2-10-2 | |

| Knight, W | 16-18-7 | 0-19-22 | |

| Kelly, James | 16-18-5 | 1-2-13 | |

| Keenan, C | 22-16-8 | 1-2-20 | |

| Kershaw, F | 11-19-5 | 0-14-2 | |

| Lane, R | 31-14-4 | 1-15-15 | Roger Lane, who worked with the Maywood brothers at the Nineteen Mile. |

| Leary, M | 34-6-3 | 2-11-14 | |

| Long, Thomas | 32-3-11 | 2-0-7 | |

| Long, Thomas | 27-3-10 | 1-8-7 | |

| Leach, George | 10-1-10 | 0-11-21 | |

| Loughnan, E Jnr | 50-15-7 | 3-6-17 | ‘Peg Leg Ted’, one of the discoverers of payable osmiridium at Mount Stewart. Had a prosthetic leg. Loughnan Creek is named after him. |

| Loughnan, James | 54-3-5 | 3-8-10 | |

| Lyons, T | 3-15-0 | 0-5-0 | |

| Loughnan, E Snr | 42-16-3 | 2-17-2 | |

| Llewellyn, John | 47-0-0 | 2-15-0 | |

| Loughnan, George | 51-5-11 | 2-14-18 | |

| Mackersey, L | 24-1-8 | 1-18-0 | |

| Maywood, A | 32-14-2 | 2-9-13 | Brother of Ted Maywood, with whom he worked at the Nineteen Mile, along with Roger Lane. |

| Maywood, E | 16-10-0 | 1-10-11 | Ted Maywood, who worked at the Nineteen Mile with his brother and Roger Lane. |

| Mills, James & Jenner, H | — | 1-3-4 | |

| Mills, J | 57-16-3 | 4-15-18 | |

| Mills, J | 19-2-6 | 1-2-12 | |

| Moore, A | 28-16-8 | 3-14-5 | Probably Savage River digger Albert Moore, brother of Reuben Moore. |

| Morgan, William | 87-8-0 | 5-11-12 | |

| Moore, RR | 74-3-9 | 4-3-17 | Probably osmiridium digger and buyer Reuben Moore, who died at Savage River in 1925. |

| Moffitt, LJ | 53-15-10 | 2-13-19 | |

| Martin, J | 6-0-0 | 0-6-0 | |

| Manion, Thomas | 26-4-2 | 1-12-23 | From the Beaconsfield family of Manions? |

| Mallinson, RD | 17-0-0 | 0-17-0 | |

| Meares, RK | 11-11-7 | 0-13-15 | |

| Matthews, T | 15-0-4 | 0-17-16 | Possibly ‘Winger’ Matthews, who appeared in Marie Bjelke Petersen’s novel Jewelled nights as ‘Wingy’ Matthews. |

| Major, J | 85-2-10 | 5-0-4 | |

| McAvoy, D | 82-1-11 | 5-19-1 | |

| McAidell & Hill | Probably CL McArdell and Harry Hill, the latter being a well-known digger who was later at Adamsfield. | ||

| McCaughey, LB | 37-3-1 | 2-4-20 | |

| McDiamid, William | — | 0-10-0 | |

| McGuiness, A | 32-2-9 | 1-18-19 | |

| McGuire, J | 44-18-9 | 3-14-12 | |

| McCormack, Charles | 33-5-0 | 2-4-8 | |

| McGuiness, F | 28-4-1 | 1-10-21 | |

| McCaughey, M | 43-14-4 | 2-8-6 | |

| McCaughey, William | 15-14-9 | 0-16-14 | |

| McQueeny, F | 11-14-2 | 0-11-17 | |

| McArdell, CL | 30-19-9 | 1-16-11 | |

| McDonald, Alex | 8-10-0 | 0-10-0 | Of Flea Flat, Nineteen Mile Creek, where he shared a hut with Jim McGinty until the latter’s death in 1920. |

| Newman, M | 21-15-9 | 1-5-9 | |

| Newman, M | 37-18-7 | 2-4-15 | |

| Nelson, H | 40-0-0 | 2-0-0 | |

| Osborn, WH | 44-4-3 | 2-13-10 | |

| Oakley, H | 21-16-4 | 1-8-1 | |

| Oakley, J | 38-5-11 | 2-12-4 | |

| Oakley, H & Loughnan, J | 7-10-0 | 0-10-0 | |

| Oakley, RP | 9-18-1 | 0-13-5 | |

| Papworth, S | 40-0-0 | 4-0-0 | Later of Adamsfield. |

| Pearson, Robert | 103-15-8 | 6-0-6 | |

| Prouse, Charles A | 141-8-0 | 8-9-10 | Charles Arthur Prouse, son of Tom Prouse. Together in 1922 they were pictured with two large nuggets found on the upper Nineteen Mile, the one found on the dump by his father being a record 4.5 oz. Charlie Prouse later went on to Adamsfield, where he was the first bride groom on the field, marrying the bush nurse, Constance Brownfield, in 1928. Also an osmiridium buyer at Adamsfield. |

| Prouse, William | 67-9-5 | 3-12-10 | |

| Parsons, Norman | 35-12-6 | 2-7-12 | From Caveside, was part of the syndicate trying to work a hydraulic show at the Little Wilson River. |

| Prouse, J | 78-16-7 | 4-5-8 | |

| Paine, Hy | 16-18-5 | 1-2-14 | Possibly Harry Reginald Paine, later the author of a book about Waratah, Taking you back down the track … |

| Paine, W | 18-8-4 | 0-18-10 | |

| Power, T | 18-10-0 | 0-18-12 | |

| Prouse, H | 20-4-0 | 1-2-14 | |

| Paine, Thomas | 51-7-6 | 2-11-9 | |

| Reimers, J | 36-5-0 | 3-3-6 | |

| Richardson, A | 47-15-0 | 4-2-3 | |

| Richards, J | 48-10-10 | 4-12-22 | |

| Ruggeri, R | 27-12-8 | 1-12-13 | |

| Russell, J & Casey, W | — | 2-6-12 | |

| Russell, J | 67-5-7 | 3-12-19 | Osmiridium pool committee member. |

| Russell, J | 43-14-4 | 2-18-7 | |

| Ramsay, James | 62-17-6 | 3-2-21 | |

| Ruffin, H | 36-10-0 | 1-16-12 | |

| Rearden, S | 6-18-1 | 0-8-3 | Syd Reardon, from Lorinna, alcoholic prospector. |

| Schill, F | — | 1-7-0 | |

| Shea, M | 79-16-8 | 4-9-20 | |

| Sheedy, Chris | 39-15-9 | 4-7-4 | Secretary of the osmiridium pool. |

| Sims, W | 12-14-7 | 1-6-1 | |

| Simpson, PC | 34-5-6 | 1-17-21 | |

| Stanley, H | 58-11-1 | 3-13-20 | |

| Smith, WH | 34-0-0 | 2-0-0 | |

| Smith, R | 70-0-5 | 4-17-22 | |

| Spencer, T | 81-2-6 | 7-1-3 | |

| Sutton, WH | 7-17-6 | 0-10-12 | |

| Stanton, JM | 65-10-11 | 3-16-19 | Reward lease holder (with Edward Loughnan jnr) at Mount Stewart. |

| Symons, GC | 15-0-0 | 1-0-0 | |

| Spencer, John | 88-8-1 | 5-6-18 | |

| Stebbings, A | 74-6-8 | 4-6-13 | |

| Shady, William | 30-5-0 | 2-0-8 | William Antonio Shady, son of Syrian hawker and shopkeeper Antonio Shady, osmiridium buyer. Became a Waratah storekeeper. |

| Smith, Martin | 38-7-11 | 2-6-1 | |

| Sullivan, J | 36-1-4 | 2-1-11 | |

| Symons, James B | 45-18-4 | 2-11-22 | |

| Symons, James B | 105-0-0 | 7-0-0 | |

| Shaw, Thomas | 114-2-2 | 6-13-17 | |

| Sewell, J | 8-2-6 | 0-8-3 | |

| Spencer, James | 25-7-6 | 1-5-9 | |

| Symons, Charles & George | 154-10-0 | 7-14-12 | |

| Scoles, J | 6-8-11 | 0-7-14 | |

| Symons, Charles | 81-5-7 | 4-15-15 | |

| Thomas, T | 15-7-5 | 0-18-2 | |

| Thurstans, F | 61-14-3 | 4-10-15 | |

| Thorne, A | 66-7-9 | 5-6-4 | |

| Thorne, Charles | 95-4-11 | 5-10-20 | |

| Thorne, W | 33-6-9 | 2-3-4 | |

| Tudor, Lionel | 91-4-8 | 6-18-3 | |

| Tudor, Lionel | 110-5-0 | 7-7-0 | |

| Tunbridge, E | 39-3-9 | 2-17-6 | |

| Turner, H | — | 1-12-11 | |

| Taylor, James | 18-5-0 | 1-4-8 | |

| Tudor, Henry | 111-2-2 | 6-2-8 | |

| Thorne, Harold | 12-12-8 | 0-14-13 | |

| Thorne, H & W | 44-5-0 | 2-8-12 | |

| Venville, D | 36-19-2 | 2-7-12 | |

| Watkins, J | 24-15-7 | 1-8-6 | |

| Wilson, R | 54-0-0 | 4-0-12 | |

| Wilson, W | 37-17-6 | 2-10-12 | |

| Whyman, Victor | 59-12-1 | 3-14-22 | Driver for his brother Ray Whyman, storesman and packer on the osmiridium fields. Claimed to be the model for the singing driver in Marie Bjelke Petersen’s novel Jewelled nights. |

| Whyman, Arthur | 30-11-3 | 2-0-18 | |

| Whyman, Phillip | 52-6-8 | 2-17-8 | Proprietor of the Bischoff Hotel. |

| Wilson, J | 35-8-3 | 2-1-12 | |

| Wilson, Percy W | 34-18-1 | 2-3-21 | |

| Woolley, James | 4-12-1 | 0-5-9 | |

| Walters, WA | 25-8-4 | 1-5-10 | |

| Wragg, H | 12-10-0 | 0-12-12 |

[1] From AB948/1/98 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office).

Lily Gresson’s Adamsfield Airbnb

Main Street Adamsfield, 1926, with Ida Smithies and Florence Perrin. Fred Smithies photo courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

In November 1926 a Mrs Gresson advertised tourist accommodation at the Tasmanian mining settlement of Adamsfield: ‘See Tasmania’s Wild West, the “osie” diggers, Adams Falls, Gordon Gorge’.[1] What extraordinary enterprise for a simple digger’s wife 120 km west of Hobart! However, when you learn what an extraordinary woman Lily Gresson actually was, this visionary behaviour comes as no surprise at all.

A water race and the village of Adamsfield, 1926, Fred Smithies photo courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Her old school Airbnb advert was probably shaped by two events: meeting the one-man promotional band Fred Smithies; and a memorable outing she made to the nearby Gordon River Gorge. Visiting Adamsfield by horseback and pack-horse in February and March 1926, Smithies, an amateur tourism promoter, had snapped the town and its jagged skyline for his travelling lantern-slide lecture ‘A trip through the wilds of the west coast and the osmiridium fields’. ‘Gorges of inspiring grandeur’ and ‘magnificent mountain scenes’ also transfixed Gresson. Decades later she recalled that

‘the scenery to the Gordon River was indescribable. Peak after peak of snow-capped mountains and the Gordon Gorge was so precipitous we would scarcely see the bottom … [it] … was like so many battlements’.

Her party ‘cheerfully stalked along the ten miles of wonderful scenery singing bits of popular songs. This was the first time I had heard [‘]Waltzing Matilda[’], she recalled, ‘and it certainly cheered and helped us along, and home again, when we’—Lily and her husband Arthur Gresson, a veteran of the Siege of Mafeking during the South African War— ‘were beginning to flag’.[2]

Certainly the outing would have come as welcome relief from the routine of life on the Adamsfield diggings. The Gressons had rushed to Adams River in the spring of 1925, after the Staceys from the Tasman Peninsula and their mates struck payable osmiridium. Lily was a woman of great conviction. At a time when few women dared venture among the thousand or so men on the ossie field, she secured her own miner’s right, put together a side of bacon and other requisites, bundled her twelve-year-old son Wrixon onto the train and off they went to Fitzgerald, the western terminus of the Derwent Valley Line, to join Arthur.

Fitzgerald was still 42 km from Adamsfield. Meeting his family there, Arthur hired five horses, including one for Wrixon, who had never ridden a horse before, one for the packer and another to carry the three months’ supply of food and equipment. It was snowing. In parts of the Florentine Valley the mud was up to the horses’ girths, Lily recalled,

‘and they slithered, slipped and plunged into the side track to keep themselves steady. The track was narrow, hastily prepared in very thick scrub, corduroyed also hurriedly—the edges not even adzed. I pitied the poor ‘gees’ [horses] slipping and floundering to try and gain firm footing. I thought I would soon be slipping over their heads and called out to my husband, “Shall I dismount?” “Certainly not”, was the reply, “or you will never get up again.” So I stayed on as best I could following the packer’s lead, for I was behind him. Presently, just around the corner, he shouted, “Look out, the down packs are coming!”’[3]

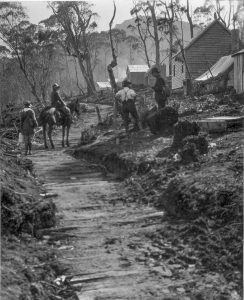

A packer leading a pack-horse team out of Fitzgerald, taking supplies into Adamsfield, 1925. Alf Clark photo courtesy of Don Clark.

This was pack horses returning unsupervised from Adamsfield. When the osmiridium field was reached, the horses were simply released to find their own way back down the track to Fitzgerald. Given that there was no feed between the two centres, the hungry animals galloped wherever they could, a nasty surprise for the uninitiated coming the other way. How the horses survived the return trip without a broken leg is hard to imagine.

The Gresson party stopped for the night at Chrisp’s Hut, a leftover from the 1907 Great Western Railway Survey.[4] It took a further day to reach Adamsfield over the ranges. The mining settlement was ‘a busy seething mass of men and horses, to say nothing of a vast morass of mud, with short stumps sticking up everywhere, quite enough to topple us over’. Arthur Gresson was living in the sort of tent-hut typical of a temporary miner’s quarters. Wrixon slept on a bench in a bark humpy with only a hessian curtain to keep out the cold, while his parents bunked down under a tent fly.

Having obtained the miner’s right, Lily was entitled to peg her own claim measuring 50 yards by 50 years (that is, about 45 metres square), and she set out next morning suitably attired in her lace-up mining boots, riding breeches, short coat and emerald-green rain hat. After she had dug a hole almost two metres deep and obtaining osmiridium-bearing earth, a man ‘jumped’ her claim, taking all the valuable ‘wash’ before she even knew it had happened. Arthur Gresson sent the intruder packing, but the damage was done, and Lily had to start again on a new claim. Soon she was winning tiny nuggets of coarse ‘metal’ by sluicing the ‘wash-dirt’.[5]

The Gressons remained at Adamsfield through the tough winter of 1926, when the diggers tried to counteract a reduced osmiridium price by selling their metal directly to London. It was tough going through that winter. Many left the field, while others stayed and suffered. Lily recalled the time nineteen-year-old digger Maxwell Godfrey went missing on an icy-cold night. He curled up under a log in the bush, but his legs were frostbitten. Nurse Elsie Bessell, who had only a tent for a hospital, could do little for him, and the news got no better after he was stretchered out to Fitzgerald, slung between two horses. Both his legs were amputated below the knee.[6] A public subscription raised about £500 to help him, and soon he was walking again with the aid of prosthetics.[7]

Lily Gresson, who had had some nursing experience in London, again showed her versatility by looking after the two patients in the hospital while Nurse Bessell accompanied the incapacitated man out to the railway station. Perhaps Lily also home schooled thirteen-year-old Wrixon. There were few children and no school at Adamsfield at this time, so otherwise he would have lost a year of his education.

And the Gressons’ Air B’n’B house? Well, while it was hardly the Adamsfield Hilton, it was comfortable enough by mining frontier standards—a paling hut with a big fireplace and a real glass window.[8] Lily Gresson might have been just a little ahead of her time. Hikers would soon be on their way to Adamsfield and the glorious south-west beyond. Ernie Bond would be besieged with them at times on his Gordon River farm, Gordon Vale, during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1952 the Launceston and Hobart Walking Clubs would even inherit Gordon Vale. Lily Gresson , pioneer of the Adamsfield diggings, was onto something!

With thanks to Dale Matheson, who showed me this story.

[1] ‘Board and residence’, Mercury, 23 November 1926, p.1.

[2] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, the author, 1987, p.194.

[3] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, p.190.

[4] In her account, Lily Gresson did not mention the notorious ‘Digger’s Delight’, the sly-grog shop and accommodation house that accompanied Chrisp’s Hut soon after the Adams River rush began. Perhaps Ralph Langdon and Bernie Symmons had already moved on into down-town Adamsfield, building Symmons Hall with its accompanying illegal boozer.

[5] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, p.192.

[6] ‘Bush nursing’, Mercury, 22 July 1926, p.11; Elsie G Bessell, quoted by Marita Bardenhagen, Adamsfield bush nursing paper, presented at the Australian Mining History Association conference at Queenstown, 2008; ‘Sufferer in bush’, Mercury, 24 May 1928, p.5.

[7] ‘Maxwell Godfrey Fund’, Mercury, 27 July 1927, p.3; ‘Maxwell Godfrey walks again’, and ‘Sufferer in bush’; both Mercury, 24 May 1928, p.5.

[8] Lily Gresson; quoted by Fred A Murfet, in Sherwood reflections, p.192.

A tale of two Staceys: Jim and Tom Stacey and the Adamsfield rush

Jim Stacey, with beard and hat, peering into the camera, at a public function late in life. Photo courtesy of Maria Stacey.

It was Tasmania’s biggest rush since the Lisle gold craze of 1879. The year was 1925, the commodity was osmiridium, the place was the Adams River, 120 km west of Hobart—and the name on everybody’s lips was Stacey.

Two generations of Staceys, a Tasman Peninsula family, drove the discovery and development of what became Adamsfield. Yet the story of the brothers Jim and Tom Stacey shows how capriciously fortune was apportioned to mineral prospectors. Perhaps Jim Stacey somehow offended St Barbara, patron saint of miners. For all his initiative and enterprise in the field, he made no money. His brother, on the other hand, turned up when the work was done and made a killing.

Jim Stacey was born at Port Sorell on 28 October 1856 to Robert Stacey and Kara Stacey, née Eaton.[1] As a young man, tin commanded his attention. By the age of 20 he was at Weldborough, on the north-eastern tin fields, with two of his brothers, one of whom died there from suspected exposure.[2] Jim Stacey then went to the Mount Bischoff tin mine at Waratah, where his mining education continued. He recalled meeting the mine’s discoverer James ‘Philosopher’ Smith, and learning from him the importance of testing river sands for minerals. Stacey benefited from meeting some of the best prospectors on the west coast—WR Bell (discoverer of the Magnet mine), George Renison Bell (Renison), the McDonough brothers (Mount Lyell), Frank Long (Zeehan) and others. The independence of these men impressed him. He was probably at Mount Lyell in 1886 during the excitement over the Iron Blow, and he later recalled testing the Franklin River for gold.[3]

The Mount Bischoff Co and Don Co plants at Waratah, c1890, courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

While at Waratah, Jim Stacey had also married Henrietta Davis.[4] Perhaps the couple had put away some money, because they established a farm at Nubeena on the Tasman Peninsula, where the Stacey family were now settled. By 1907, when he was 51 years old, Jim Stacey was a respectable member of Peninsula society, being an inaugural member of the Tasman Municipal Council.

Jim Stacey’s much younger brother Thomas Arthur Stacey was also a mineral prospector, but there the similarities end. Tom was also born at Port Sorell, but in 1877, 21 years after Jim.[5] Little is known of his early years until in 1906 he married Edith Grace Wright at Koonya on the Tasman Peninsula.[6] To say the marriage was an unhappy one would be an understatement.

During World War One (1914–18), Jim Stacey was the model of patriotism, ‘sending’ five sons to the battlefields and being active in recruitment.[7] Two of those sons were killed, another two were wounded.[8] Other people sought an escape in the war. So it was for Tom Stacey, who must have owned the most peculiar war record in his family. He enlisted at Claremont, Tasmania, under the alias John West to avoid maintenance payments to his estranged wife and children.[9] When the police tracked him down, he deserted, eventually re-enlisting, under his real name, at Cloncurry in outback Queensland. Stacey reached Cape Town on the troop ship Wyeema in 1918, just as the Armistice was being signed. Returned to Sydney with the rest of the 7th General Reinforcements, he was arrested as soon as he was discharged.[10]

In his sixties, Jim Stacey was reborn as a prospector. The catalyst for it was the discovery of belts of serpentine, the host rock of osmiridium, in south-western Tasmania. In 1924 he led a party which included Fred Robinson, Edward Noye, and his sons Sydney and Stanley Stacey to Rocky Boat Harbour (Rocky Plains Bay) near New River Lagoon. Announcing the discovery of osmiridium there, the old Bischoff man proudly asserted his independence, stating that he took no aid from the government, having first found the metal while prospecting on his own account months earlier.[11] The first sale of osmiridium from southern Tasmania was in January 1925 when Arthur (AH) Ashbolt of AG Webster & Son in Hobart bought a 25-3-13-oz parcel worth £780-10-0 from Nubeena men Robinson, Noye, Jim Stacey and C Clark.[12]

In November 1924 Arthur, Sydney and Charles (‘Brady’) Stacey, plus ‘Archie’ Wright and Edward Bowden of Hobart retraced Government Geologist Alexander McIntosh Reid’s steps by working their way along the South Gordon Track to the Gordon River, then back along the Marriott Track to the Adams River Valley, discovering osmiridium on the western side of the Thumbs.[13] Wanting confirmation of their find from the experienced Jim Stacey, they arranged to meet him at the Florentine River in February 1925. Jim Stacey and party made their own osmiridium discovery independently on a different site near the head of Sawback Creek, the eastern branch of the Adams River, 120 km west of Hobart by railway, road and sodden, steep mountain track.[14]

From July to September 1925, a quarterly record 1078 miner’s rights were issued in Tasmania, as diggers rushed the field.[15] Jim Stacey was reported to have chosen his reward claim hastily, and won little from it, whereas, ironically, his brother Tom, who had had no part in the early expeditions, ended up with the best claim on the field.[16] In the December quarter for 1925 alone, Tom Stacey pocketed £1186—the equivalent of a six-figure sum today.[17]

Adamsfield ‘new chum’ Horace ‘Jimmy’ Lane recalled turning down Tom Stacey’s invitation to join him as a partner in that rich claim. Lane disliked and feared the unshaven, unkempt ‘Old Tom’, attributing his manner and habits to over-indulgence in rum. Old Tom was well known for the ‘boom and bust’ lifestyle that must have been little comfort to his long-suffering family.[18] North-eastern identity Bert Farquhar may have been exaggerating when he alluded to Tom leaving the field with £12,000 and returning two years later unable to afford a horse to carry him, but the lesson was obvious.[19] Lane told the tale that

‘on one occasion Old Tom had crossed Liverpool Street [Hobart] to test the quality of the liquor at the Alabama Hotel. A naval vessel was in port and there were quite a few sailors in the bar of the Alabama and Tom was getting somewhat more inebriated than usual. He finally reached the point of no return: he offered to fight anyone in the bar for £10 and threw a tenner on the bar to back himself. One of the naval chaps agreed to fight him so Tom demanded that his tenner be covered. However when he turned around there was no money on the counter and no one present would admit having touched it. Tom staggered back to the Brunswick [Hotel, on the opposite side of Liverpool Street] quite convinced that he had lost £20 not £10’.[20]

Hobart General Hospital records show that in 1926 Tom Stacey had sutures inserted in a cut in his face sustained while fighting at Adamsfield.[21] His alcohol-fuelled lifestyle is easily traced today through digitised newspapers. Whatever money he made was soon spent, and he became the epitome of the old diehard prospector. In 1950 Tom Stacey was described as a 73-year-old ‘hermit’ living in a one-room shanty in the bush near Coles Bay, with only a dog for company. That dog hunted kangaroo meat, Old Tom had apple and cherry trees and grew vegetables to sell to guests at the nearby Coles Bay guesthouse. His bed was ‘a piece of sacking spread with fern’, and his ancient trousers were held together only by pieces of wire.[22] He was killed when hit by a car on the Tasman Highway near Sorell in 1954.[23]

Jim Stacey continued to prospect almost until his death in 1937.[24] In 1935, for example, when he was 78 years old, he and two of his sons were paid by the government to spend ten weeks prospecting the Hastings–Picton River area.[25] He died in the company of family and was remembered for his public service, not the least of which was leading the way to Adamsfield, where some gained a start in life and others scraped a living through the Great Depression. Stacey Street, Adamsfield, is overgrown by bracken fern, and Staceys Lookout on the Sawback Range, unvisited, but the twisted landscape of the mining field still recalls his skills, perseverance and vision.

[1] Birth record no.1518/1886.

[2] ‘Sudden death at Thomas Plains’, Launceston Examiner, 29 May 1878, p.2.

[3] RJ Stacey, ‘Exploring for minerals’, Mercury, 8 December 1907, p.6.

[4] The marriage on 18 February 1886 was registered at Emu Bay, no. 1266/1886.

[5] Birth record no.1687/1877.

[6] ‘Family notices’, Mercury, 2 June 1906, p.1.

[7] ‘The recruiting scheme’, Daily Post (Hobart), 17 February 1917, p.7; ‘Workers’ Political League’, Mercury, 21 December 1916, p.5.

[8] For the death of John Stacey, see ‘Tasmania: Nubeena’s avenue of honour’, Mercury, 5 November 1918, p.6. William Stacey joined E Company, in the New Zealand Army (see Nominal Roll, no.62, p.19, 1917). For his death see ‘Roll of honour: Tasmanian casualties’, Examiner, 12 November 1918, p.7. Thomas Albert Stacey and Robert Stacey were both wounded twice in France. Robert was also shell shocked.

[9] John Hutton to Sergeant Ward, 2 September 1916, SWD1/1/713 (TAHO).

[10] Note added to Police Gazette (Hobart), 12 January 1917, p.10.

[11] ‘Osmiridium: reported discovery’, Advocate, 8 September 1924, p.2.

[12] ‘Register of osmiridium buyers’ returns of purchases, September 1922–October 1925’, MIN150/1/1 (TAHO).

[13] ‘Mining reward: discovery of osmiridium’, Examiner, 20 December 1934, p.7.

[14] PB Nye, The osmiridium deposits of the Adamsfield district, Geological Survey Bulletin, no.39, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1929, p.3.

[15] ‘Osmiridium: Tasmania’s unique position’, Mercury, 29 September 1925, p.9.

[16] ‘Romance of Adams River’, Examiner, 25 December 1925, p.5.

[17] ‘Register of osmiridium buyers’ return of purchases’.

[18] For the trials and tribulations of Edith Stacey and her four children, see file SWD1/1/713 (TAHO). For Tom Stacey’s battles with liquor laws, see, for example, ‘Police Court news’, Mercury, 13 August 1927, p.3. Convicted of sending a child to buy alcohol for him, Stacey took six years to pay the small resulting fine (Police Gazette, 6 October 1933, p.204).

[19] Bert Farquhar, Bert’s story, Regal, Launceston, 1990, p.3.

[20] Horace Arnold ‘Jimmy’ Lane, I had a quid to get, the author, Stanley, 1976, p.63.

[21] ‘Register of applications for treatment, Outpatients Department’, Hobart General Hospital, 11 September 1926, HSD130/1/3 (TAHO).

[22] ‘A solitary bushman’, Examiner, 16 September 1950, p.7.

[23] ‘New clue found to hit-run motorist’, Mercury, 25 August 1954, p.5.

[24] Nubeena’, Mercury, 5 January 1938, p.9.

[25] See file AB964/1/1 (TAHO).